Introduction

Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin, British Ambassador to the Sublime Porte of Constantinople (Istanbul) the seat of the Ottoman Empire at the turn of the 19th century, having stripped down the monuments of the Acropolis from 1801 - 1804 brought back to London one whole caryatid from the Erechtheion, huge pedimental figures, friezes, metopes and parts of columns from the Parthenon and other pieces representing over half of all the surviving sculptures from the monuments.

These were sold to the British Government in 1816, after the Select Committee of the House of Commons had debated the issue and considered the method of their acquisition, their value and the importance of buying them as public property. At the conclusion of this procedure, in spite of some serious misgivings expressed by a number of MPs and witnesses, especially whether a British Ambassador was justified in using his position to acquire antiquities from the Government he was accredited to, Elgin won the day. Parliament decided the sculptures be bought at the recommended price of £35,000.00, that they remain together and be displayed at the British Museum which maintains to this day that the so-called ' Elgin Marbles' are legally and properly held by it. Scholars have now seriously disputed this claim in the light of recent research and findings especially concerning the validity of the so-called firman.

Hacking the Parthenon Over and Over

In the year 1799, the 7th Earl of Elgin, was appointed Ambassador at the Sublime Porte of Constantinople in Ottoman Turkey, 'not without lobbying on his own part'. Elgin had been engaged for some years building a grand country house, to be called Broomhall. The architect was Thomas Harrison, a fine architect in the Greek style and passionate admirer of Greek classical architecture, who strongly encouraged Elgin to arrange for drawings to be made of the Greek antiquities in Athens and especially "… to bring back plaster casts in the round of the actual surviving objects. There was no suggestion at that time that the original remains themselves should be removed."

Athens at the turn of the 19th century and after three and a half centuries of Ottoman occupation was a village of 1300 souls, clustered around the Acropolis. The population did not exceed some ten thousand of whom half were Orthodox Greeks and the rest Muslim Turks (who all spoke mainly or even only Greek), Albanians (half of them Muslim and half Christian Orthodox) with a sprinkling of African Muslims, Jews, Roman Catholics and a handful of western European families.

Locating the Bribeable Dignitary

The Athenians were thrilled with the arrival in 1800 of the Elgin team hoping it would create jobs and bring money to the city. Amongst them was the Reverend Philip Hunt - a deft negotiator consumed by an insatiable appetite for Greek antiquities - and the Italian Giovani Batista Lusieri - a professional landscape painter, in charge of the whole project.

To start with, Lord Elgin's aims were modest: as Britain's ambassador he used his considerable influence with the Sultan to be allowed to draw and make casts of the Parthenon sculptures. He wished to bring such sketches and casts back to Britain so as to improve artistic appreciation and taste among his countrymen. However, the more he busied himself with this project the more he realised that under the eminently bribeable Ottoman officialdom in charge, the Parthenon sculptures were there not only for copying but also for the taking.

The two Ottoman dignitaries mentioned in the correspondence of the team members were the Voivode, governor of Athens, and the Disdar, the military governor of the Acropolis, then a publicly owned military complex under the authority of the Sultan himself. Intrigued by the fascination the Acropolis exerted on Western visitors these two were not averse to sell them the odd piece of it but kept quiet about it lest they lose their heads (literally).

With such a Damocles' sword over him, the Disdar was prepared to sell access to the Acropolis but when it came to allow the Elgin team to sketch, including perhaps the military fortifications and even spy on women in the Ottoman houses visible from the Acropolis, he drew the line. He demanded a firman (Sultan's decree). Lord Elgin In Constantinople started to work hard to obtain one.

In February 1801, six whole months after their arrival in Athens, Lord Elgin's artists were finally allowed on to the Acropolis. However, when the scaffolding was erected and the moulders were ready to start work, the Disdar took fright and banned access to the site until the promised firman was securely in his hands.

The Story of the Elusive Firman

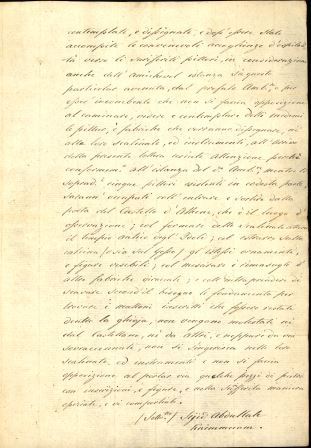

In spite of claims by Elgin's men at the time of the removals, and the British Museum in later and recent years, no "firman" was ever produced either at the Select Committee in 1816 or in later years when serious doubts were expressed about the existence of a firman in the first place (See below: The firman and the legitimacy of the acquisition). The only written evidence is that of an Italian translation of an "official letter" now in the possession of William St. Clair, a Cambridge historian. However, the following is the account of the granting of a so-called "firman" as given in evidence at the Select Committee in 1816 and repeated ever since by all who wish to retain the Marbles in Britain.

The first firman was issued in May 1801 and appears to have been sent directly to the Ottoman officials in Athens through Ottoman channels. Its contents have never been known but one can surmise that it allowed Elgin's team access to the Acropolis to draw, erect scaffolding and make moulds.

This was soon deemed insufficient by the team. So Hunt asked for a second firman that would give them permission 'to dig, to take away any sculptures or inscriptions which do not interfere with the works or walls of the citadel'. Granted on 6 July 1801, this alleged firman - or 'official letter' as the Select Committee calls it - was discovered in its Italian translation by William St.Clair in the Hunt papers held by the family. It authorises Elgin 'to remove some stones with inscriptions and figures'. Even by these terms, Lord Elgin was given per mission to copy, draw, mould and dig around the Parthenon but not to saw sculptures off the monument.

A month later, in August 1801, Hunt asked the Voivode to allow him to take down the metopes from the Parthenon, a move that even Logotheti, the Greek Vice-Consul of Britain in Athens was reluctant to approve. The event was witnessed and described by Edward Daniel Clarke (1769-1822), a British scholar, traveller and coin collector in his Travels Part II, section 2, p.483. 'One of the workmen' he writes 'came to inform Don Batista that they were going to lower the metopes. We saw this fine piece of sculpture raised from its station between the triglyphs: but while the workmen were endeavouring to give it a position adapted to the line of descent, a pair of adjoining masonry was loosened by the machinery and down came the fine masses of Pentelican marble scattering their white fragments with thundering noise among the ruins. The Disdar, seeing this, could no longer restrain his emotions; he actually took his pipe from his mouth and letting fall a tear, said in a most emphatic tone of voice 'telos.' ['The end!' or 'Never again!'] positively declaring that nothing should induce him to consent to any further dilapidations of the building'.

Stripping the Acropolis Repeatedly

The end ('telos') was, however far from near. In the spring of 1802 Elgin came over to Athens himself, congratulated his team and oversaw personally the removal of the stunning horse's head from the chariot of the waning moon (Selene) in the east pediment.

Shipping the sculptures to London presented problems. In September the 'Mentor', Elgin's own small brig, sank outside the Island of Cythera with some of the finest sculptures of the Parthenon. On Christmas Eve 1802, Hunt managed to enlist the help of Captain Clarke, commanding the HMS 'Braakel', to salvage the sunken sculptures and ship them to London.

Lord Elgin left Constantinople with his family on 16 January 1803, was captured by the French and held prisoner for the next three years. During that time his man in Athens, Lusieri, removed one of the Caryatids of the Erechtheion and replaced it with a crude bare brick pillar to prevent the roof from collapsing.

By 1806, when Elgin was released from captivity, his second large collection of antiquities was still In Athens with the beleaguered but loyal Lusieri standing guard over It. When in 1809 the new British Ambassador Robert Adair asked for their release, the Ottomans told him that Lord Elgin had never been authorised to remove any sculptures from the Parthenon In the first place. On 18 February they changed their mind and the Voivode was ordered to let them go.

The order reached Athens on 20 March. Losing no time, Lusieri loaded everything on a ship that set sail for London on 26 March. It contained most of the Parthenon sculptures but had to leave behind five of the heaviest cases. These were shipped to London a year later on 11 April 1811 by a British navy vessel having on board Lusieri and his last cargo 'the last plunder from a bleeding land' as Byron was to call it in Childe Harold's Pilgrimage.

The Firman and the Legitamacy of the Aquisition

Dr. Jeanette Greenfield in her highly regarded book "The Return of Cultural Treasures" (First published 1989, 2nd edition 1998, Cambridge University Press) has this to say on the firman:

"Although there has been debate as to the extent that the firman empowered Lord Elgin, the real issue in my view, centres around the fact that the original firman was never produced by Elgin in the House of Commons Parliamentary Select Committee in 1816. Only a copy written from memory was produced. There is no direct documentary proof of the right to remove the marbles. Even regarding such documents as exist there are arguments over the interpretation of the alleged wording which would not have been stretched to justify destruction of the Parthenon."

In 1998, an eminent Greek historian/Turkologist, Professor Vassilis Demetriades, wrote an article on the real nature of the Turkish firman, following extensive research on Ottoman administration and having examined a huge number of Ottoman archives both in Greece and in Turkey (Constantinople). These are some of his findings:

"In the Ottoman Empire there was no legislative body to debate or enact the state's legislation. Only the 'holy law of Islam' was acceptable as the basis of the state and the Sultan's right to amend the provisions of the holy law, wherever necessary. This right was expressed in 'firmans'. Elgin claimed that he had secured such a legal document, but was the document presented as such a firman? Professor Demetriades questions this:

"Any expert in Ottoman diplomatic language can easily ascertain that the original of the document which has survived was not a firman. "Ferman" in Turkish denotes any order or edict of the Ottoman Sultan. In a more limited sense it means a decree of the Sultan headed by the cipher (tughra) and composed in a certain form. All firmans have some common features that distinguish them from documents of other types.

Professor Demetriades lists all these features in great detail and concludes:

As none of these features are present in the document produced, the document whose translation we have is not a firman." Professor Demetriades believes on present evidence that there has never been a "firman".

Some apologists of the British Museum have claimed that the British used the word "firman" to describe any official letter issued in the Ottoman Empire. That maybe so, but that suggests that the legal weight of a proper firman allowing Elgin's men to enter the Acropolis has never existed. Instead it appears that an obliging Vizier simply sent a letter of introduction giving instructions for Elgin's men to be allowed to enter the Acropolis with specific guidelines for acting there.

Guidelines that were most emphatically never followed.

"...I think had it not been for great emotion, my ancestor would never have done what he did. I mean had he been dull and insipid and so on, he would have just had his artists make their drawings and then he'd have shrugged his shoulders and then he should have finished, gone away.

Asked if he sometimes wished his great-great-grandfather had never done it, Lord Elgin replied: "Goodness, yes."

The eleventh Earl of Elgin talking of his meeting with Melina Mercouri.

Comments powered by CComment