Athens International Conference, 26 June 2014

'PARTHENON. The Integrity of a Synbolic Monument. The Role of the Citizen. An International Campaign' organised by the Marianna Vardinoyannis Foundation in association with the Melina Mercouri Foundation

William St Clair

William St Clair

Author of Lord Elgin and the Marbles revised edition 1998, The Elgin Marbles, Questions of Stewardship and Accountability, 1999, That Greece Might Still Be Free, the Philhellenes in the War of Independence, new edition in open access, 2008, and other works. He is Senior Research Fellow at the School of Advanced Study, University of London, and of the Centre for History and Economics, Cambridge and Harvard.His essay on 'Looking at the Acropolis of Athens from Modern Times to Antiquity' will be published later in the summer.

First let me say how much I feel honoured and delighted to have been invited and to have the opportunity of offering some ideas. Many people here know far more than I do and I have to be severely selective, but I hope to pick out points that may be relevant to question of what is best to do now.

With written records on the Acropolis of Athens back to Homer and archaeological evidence even earlier, there is no site in the world in which the long view is so long, the ways of seeing so different, the stories told and the claims to legitimacy so varied, and the evidence available for building an understanding so complete.

This experience, that is retrievable, and therefore transferrable, is, I would say, an inheritance as precious as the marble.

In that long history, the question of return is quite recent, just over two hundred years, but in terms of modern notions of cultural property, with only a few scattered predecessors, it covers the whole age, and provides the paradigm for all the arguments.

I can begin with ideas based on legality

The cartoon above, that shows the Ottoman governor of the Acropolis remonstrating with Elgin is from 1824, but the complaints began earlier, with doubts being cast on the legitimacy of the firman, the letter from the highest official in the Ottoman government writing in the name of the Sultan.

There has been much writing about the legal force of this document. But there are risks in applying present day law and modern legal concepts to historical situations in which very different laws and customs applied. The reason Elgin needed the Sultan's permission was that the Acropolis was a military fortress. There are other firmans in which the Sultan allowed removals of antiquities from fortresses, that I have seen. And it is worth recalling that international law included right of conquest as well as treaty transfer at least until the late nineteenth century. If you look at the website of the British Royal family you will see that it includes both as the legal foundation for its historical legitimacy. As far as the Acropolis is concerned, we have well documented records of legal transfer back to 1205 and probably earlier. But my main point is this. The whole approach of trying to build a legal case is backward looking. So I would say it would be better to look forward from the historical moment in which we find ourselves

Another set of arguments relate to claims of Hellenic continuity. I was among those lucky enough to be invited to meet Melina Mercouri when she came to London as Minister of Culture in 1986. I was quite seduced, but although I was in favour of return, I could not go along with her nationalist myth-making, such the story she told of the Greeks at the time of the Revolution offering to share their bullets with the Turks if they would spare the Parthenon. And that remains my view. We cannot honour classical Athens by disregarding, setting aside, or compromising with their intellectual achievements, that include separating a search for truth about the past from telling stories about the past to serve the present.

We should, I suggest, be wary of using antiquities for 'nation-building' that can easily slip into myth making. As Plato and Socrates knew, the aspiration to 'make the mute stones speak' is an illusion. The stones can only speak when some human being speaks on their behalf. And questions therefore arise about who deserves to be accorded that privilege, and on what intellectual, including historical, authority do the offered stories rest?

It was on the same trip to London that Ms Mercouri made her famous remark, 'There are no Elgin Marbles!' She was picking up on a point of language that the act of re-naming can be an appropriation, an annexation, and an attempt at legitimation of a new status. Since Mercouri's speech, the phrase 'Elgin Marbles' has become politically incorrect, and is now seldom heard.

However, the phrase 'The Sculptures of the Parthenon', which has replaced it, is also unsatisfactory. It too tends to legitimate a particular way of seeing, namely, that the sculptural components of the ancient buildings of the Acropolis are of greater value than the architecture of which they formed a part, that the buildings are more important than the site, and that they can be separated from the social and cultural purposes to which they were put. The phrase, 'The Sculptures of the Parthenon', that rides on nineteenth century western romantic notion of autonomous 'works of art', and its conceptual hierarchies, itself concedes much to the opponents of return. The current phrase would therefore be only partially corrected if it were modified to, say, 'The Sculptures from the Parthenon.'

It is well know that in the ancient authors, the Parthenon is seldom mentioned. In ancient times, from Homer to Julian, it is the Acropolis that is appealed to, whether to warn, to shame, to educate, or to celebrate. And it is the whole visible Acropolis rock, slopes and summit, buildings and freestanding statues and dedications, myth and history, the natural as much as the man-made.

The collection of antiquities brought from the Acropolis by Elgin included substantial pieces of all four of the classical buildings on the Acropolis summit, and of the Monument of Thrassylos on the south slope. I took a few photographs in the British Museum in preparation for this occasion.

Here is part of a Parthenon capital with a column drum that comes from elsewhere and does not fit.

It has had to be replaced on the building by a replica

And part of the Erechtheion

And of the Nike temple

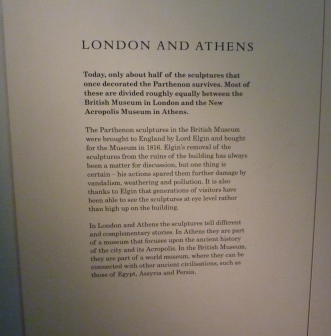

So what arguments are deployed by upholders of status quo, of whom, incidentally there are vanishingly few in the UK? The old 'rescue and stewardship' that was in standard use from Elgin's day until the late 1990s has been largely withdrawn from, rendered unsustainable by the revelations of the damage done to the Marbles in the 1930s, and by the even more damaging revelations of the extent of the officially sanctioned systematic misleading of the public and scholarly world, and of the long-persisted-in illegalities. It was hurriedly replaced by a newly invented justification, called the 'universal' or 'encyclopedic' museum, and the labels have been altered to fit.

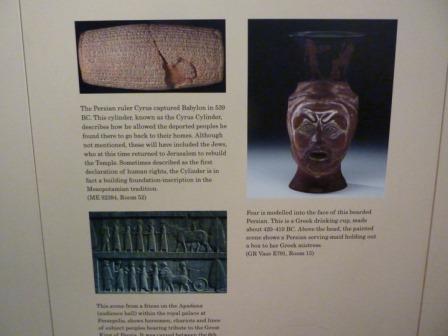

The separated parts of the frieze in London and Athens, we are now told in a phrase dreamed up by some PR guru or spin doctor, tell 'different but complementary stories.' And in support of this new narrative we see attempts to downplay classical Hellas. Who would have guessed that the main labels in the Parthenon gallery would now refer to Persia? Including the Cyrus cylinder that is being paraded both on this label and round the world's museums as a 'declaration of human rights'.

What we are seeing here is a new danger in addition to the others mentioned so far, a kind of cultural relativism allied with a commercial consumerism. Essentially the thought seems to be 'tell the punters what they want to hear', a modern form of myth-making as damaging as the nationalism of Melina Mercouri.

And, since UNESCO are here, this may be the moment to make a wider point. The Venice Charter, now half a century old, has provided a framework for an intergenerational ethics on the conservation of sites and monuments, essentially that it is wrong to alter the built heritage to serve the ideological aims of the present. What we lack, and increasingly need, is a code of ethics that subjects the stories that are officially invented and presented to make the mute stones speak to a similar set of ethical limitations.

So how should the claim now be presented? As it happens we now have the documents for the first claim for return made in 1835 immediately after independence.

It is notable that the claim, for the Nike temple friezes, was presented in terms of what was best for the monument, for an anastelosis.

In my view that is how the claim should now be presented in the re-launch. What is best for the monument, for viewers, and for the scholarly world, and for the visitor experience, categories that coincide and reinforce one another. And by the monument here I mean the whole Acropolis.

In support of the claim I would recommend preparing a clear statement, that is forward looking and drafted to show that the claim is intended to meet the needs and opportunities of today and the future. It should celebrate the achievement of classical Hellas and Athens in particular, emphasising its historical uniqueness. Although Hellas was influenced by its neighbours, and influenced them, as nobody doubts, it is historically misleading, as well as consumerist, to imply that it was just one civilization among many.

In Athens for the relaunch I would recommend a studied attempt to avoid condescending to visitors, as is already well under way in the excellent labels here. The public deserve the best. And they are interested in the ideas not just the stones, and in the most up to date knowledge. They would, in my view, prefer to be told that Athens was one of - at the last count - forty four Hellenic cities that had forms of democratic institutions and was not the first- than that it was 'the cradle of democracy.' And the Acropolis Museum can develop further its modern information technology to present alternatives and imagined reconstructions as is already happening

These are not guidance of the 'some say this, some say that' type that, as we see elsewhere, open the way both to old myth-making and to modern cultural relativism and consumerism. They are dynamic attempts to enable visitors to comprehend alternatives where there is room for genuine debate within the traditions of science and evidence-based humanities that our predecessors revived from ancient Hellas. One of the main roles of the ancient Acropolis was to serve as an education in stone, a paideia, for citizens and visitors. You have the opportunity to set out an updated vision of that ideal in the relaunch documents and, as the pieces are returned, to make it ever more real.

Comments powered by CComment