‘200 + 20 years in captivity. The Parthenon Sculptures from Elgin to Boris’

Paul Cartledge spoke at the Culture Through Politics online event on Sunday 11 April 17:00 BST. His talk followed on from Professor Pandermalis, President of the Acropolis Museum and was made alongside other distinguised speakers.

‘Decolonising’ the Elgin-Parthenon Sculptures

First, may I begin with a huge vote of thanks: above all to the ‘Culture Through Politics’ group for organising this exceptionally important webinar, but also to my very distinguished fellow-invitees, for their important contributions.

Second, let me say a word about the title of our public webinar debate: it alludes of course to a very specific and very special anniversary, a famous bicentenary. And as a Greek historian colleague of mine has acutely observed, you tell me what anniversaries you want to celebrate/commemorate and I will tell you who you are. ‘1821’, in other words, is for Greece collectively and for Greeks individually a magical year – their ‘1789’, if you like. Or, in a way, our – English - ‘1066’! For it marks the beginning of a new Hellenic identity, but not only Hellenic: in retrospect, we can see that it was only the first step on the road to political freedom and ultimately to democratic self-determination throughout the continent of Europe.

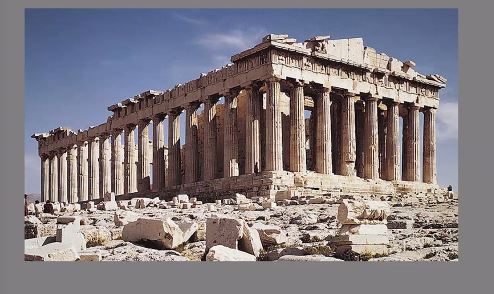

To me, however, as a historian of ancient/Classical Greece/Hellas, 2021 has another signification as a major anniversary year: it is the 2500th anniversary of what the Western world’s first historian, Herodotus of Halikarnassos, called τα Μηδικα, what we ancient historians call the Graeco-Persian Wars. As in AD 1821, so in 480-479 BC, democracy as well as freedom was at stake – as I have tried to show in a number of lectures both in Athens and online. And at the beating heart of that ancient Greek – and more especially ancient Athenian – achievement of victory and liberation there lay and there still lies a building, a unique and quite extraordinary structure, one that we today – not quite accurately – refer to for short as ‘the Parthenon’.

What I want to do in my allotted 10 minutes is try briefly to con-textualise what (Lord) Elgin and his cohorts did TO – that is, against – that building and structure in and around 1801. I do so in the hope – probably a vain hope – of bringing the UK’s current, classically-educated Prime Minister to a proper appreciation both of the enormity of that long ago act of vandalism and of what now urgently needs to be done with and FOR those Parthenon Sculptures that are currently not in Athens. Which brings me to …

Thirdly, my own chosen title: “‘Decolonising’ the Elgin-Parthenon Sculptures”. If I may, I shall begin with a little autobiography. I was born in 1947, so that by my early teens I was well aware of the – literal – decolonisation, the shedding of imperial possessions, that Britain was – under its then also classically-educated PNM, Harold Macmillan – in the process of beginning. India had already ‘gone’, ‘been lost’, to the British Empire, so the focus in and around 1960 was on the continent of Africa, and I was at first puzzled to hear that the very word ‘empire’ had become – in some, enlightened quarters - a ‘dirty word’, something to be spoken of with distrust if not contempt. As I entered my late teens – and Oxford University (to read Classics, pretty much the same degree as Macmillan read before me and Johnson read after me) – I became even more acutely aware that there was something called ‘the Third World’, encompassing huge swathes of Asia, Latin America and – of course – Africa. It seemed obvious to me that the ‘Third World’ did not exist as if by nature, but was the direct product of self-interested intervention and depredation, mainly economic but also cultural, by the countries of the ‘First World’.

By the time Melina Mercouri ,in the early 1980s, launched her campaign for the repatriation and reunification of what were then usually called ‘the Elgin Marbles’ in the British Museum, it was becoming clear to me that the fact that the British Museum held the Marbles of the Parthenon (and other Athenian monuments) was part of a broader, imperial or imperial-colonial story.

I became a very early member of the British Committee for the Restitution (now Reunification) of the Parthenon Marbles [BCRPM], as it became ever clearer to me that the ‘British Museum’ should really be known as the ‘British Imperial War Museum’. As regards specifically the Parthenon Marbles in the BM, this was not only because those Marbles had been acquired – stolen – when the British Empire was at its height and as part of a very dirty deal between Britain’s imperial representative in Constantinople and the local Ottoman authorities but also because the attitude of the British Museum Trustees towards their possession of the Marbles was – still, in the 1980s - precisely imperialist or colonialist: not only – in their view – had the Marbles been legitimately (as well as legally) acquired but also they thought the BM deserved to continue to hold them because, under the stewardship of the Trustees and the relevant Keepers and other curatorial staff since 1817, the intrinsic aesthetic and cultural value of the Marbles – the Marbles in London only, that is – had been somehow enhanced. Somehow, their stay in London was represented as so much part of the overall ‘story’ of ‘the Marbles’ that reunification of the ‘Elgin Marbles’ to Athens would somehow diminish them, all of the Marbles.

That indeed remained the status quo down to 2009 – when the entire BM colonialist-imperialist ‘narrative’ was disrupted, rendered null and void, by the foundation of the (New) Acropolis Museum (NAM), under the genial Directorship of Professor Pandermalis. A new justificatory strategy was therefore required by the BM’s Trustees, and they fell back on a supposedly decisive, and incontestable, distinction of hierarchy between ‘universal’ museums such as the BM and supposedly inferior (merely) local or national museums such as the NAM. All the while, the colonialist-imperialist line remained intact for the Trustees, who even invoked the ultimate absurdity that the Parthenon Marbles that were in the BM were better understood IN the BM – better there than anywhere else indeed, because they could be seen and appreciated in the context of all other ‘world’ cultures represented artefactually in that same (8 million…) collection. What the BM Trustees could not, however, either see or anticipate was that a big anti-colonial head of steam was building up, focused especially though not of course uniquely on artefacts looted from Africa.

I know a good deal about that anti-colonial head of steam because it has come to affect not only the Marbles but even my own discipline and profession of Classics, especially since the beginning of this year but not only since then by any means. In the very same decade that the BCRPM was founded (in 1983) scholars who were not actually Classicists began to put it about that Classics as a discipline was fundamentally flawed at its very roots and conception: it was at best an ethnocentric, at worst a racist and sexist, project of Western and male and white supremacy, rooted in the study of societies that were themselves based on slavery and generally sexist too. So, why bother to study two main ancient civilisations – the Greek and the Roman - that had so little that was admirable let alone imitable to offer us?

Needless to say, there are defences – very good defences – available to those who believe (as I do) that Classics has a great deal that is positive still to offer us, and that a key part of that is a story about freedom and democracy, a story that has at - and as - its centre the Parthenon. In my ‘Salamis 2500’ lectures I always end with the Parthenon and its place within the entire Athenian Acropolis building programme of the second half of the 5th century BC. I do so because the Athenians decided democratically to have the Parthenon built, in a quite extraordinary way, as an overpowering symbol: both of what it meant to be Greek, as the Athenians of the 5th century BC understood that – free both personally (free from) and politically (free to), self-governing, and of what it meant to be democratic – that is, giving the lion’s share of the political power of self-determination to the demos of the Athenians, the poor majority of the empowered (free, adult, male) Athenian citizens.

Of course, we must not hide the many features of ancient Athenian democracy that we today would not choose to repeat – the exclusion of women, the exploitation of non-Greek slaves – but these must be understood within the context of those, very different times. The positives also need to be emphasised, unashamedly. Which is why it matters so much to me that ALL surviving sculptures from the Parthenon currently outside Athens – not only but especially those in the BM – should be returned and reunified in Athens. As regards the BM in particular, the case for reunification is not only scholarly, not only aesthetic, but also – and perhaps above all – ethical and moral. And in that regard it is above all anti-colonial: an attempt both to repair the damage both physical and metaphorical done by Britain’s colonial representative Elgin 200 years + 20 ago, and at the same time to make a progressive statement of anti-colonialism today. It is a unique case but also one that is completely in line with and in sympathy with other campaigns affecting other museums and other cultures for the repossession and reintegration of culturally identifying material artefacts.

Professor Paul Cartledge

Taxiarches, Order of Honour, Greece

A.G. Leventis Senior Research Fellow, Clare College, Cambridge

A.G. Leventis Professor of Greek Culture emeritus, University of Cambridge