British Museum’s Parthenon gallery 10-month closure prompts concerns from Greek officials and campaigners

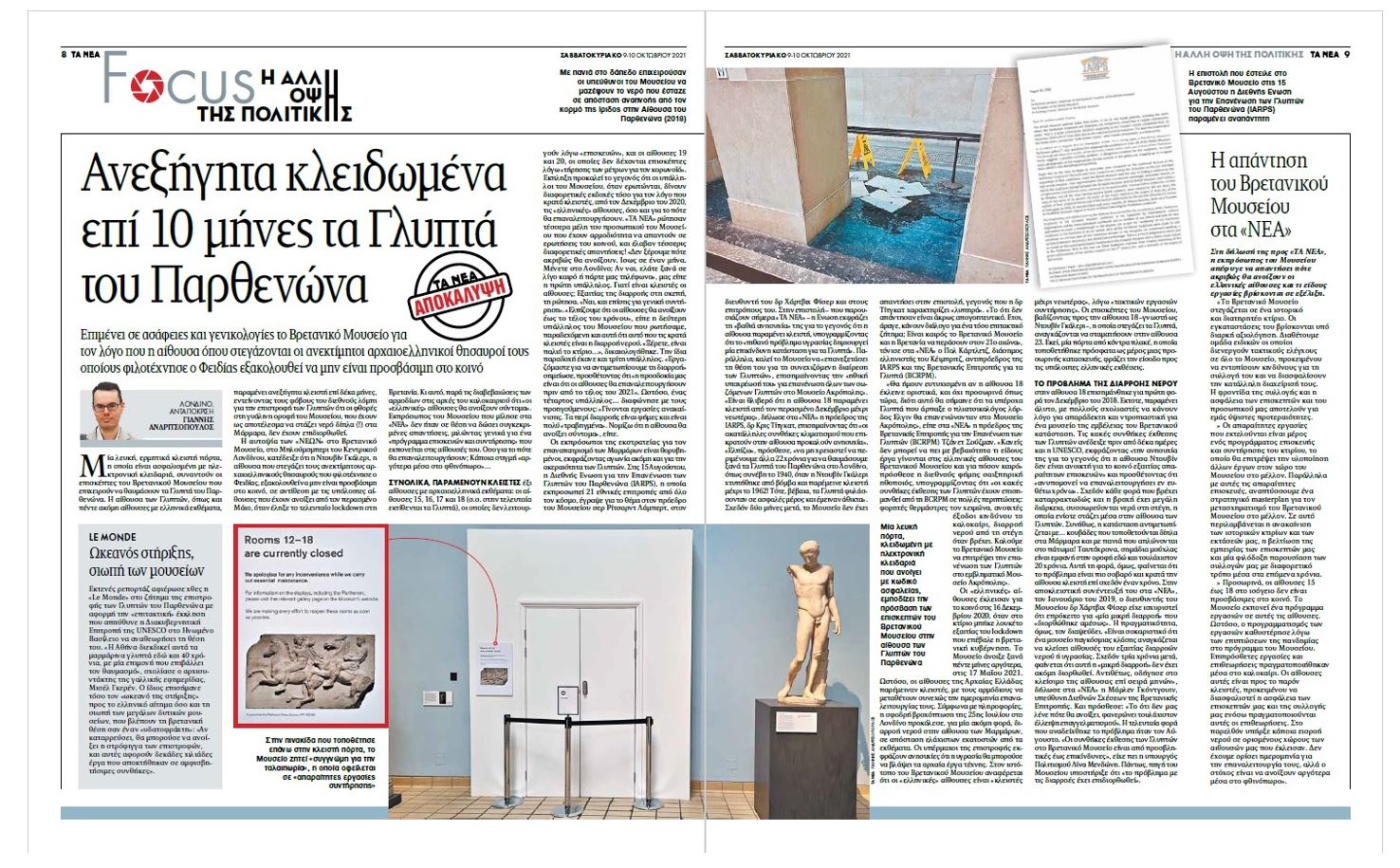

Βy Yannis Andritsopoulos, London Correspondent for the Greek daily newspaper Ta Nea, 09 October 2021

To read the original article, follow the link here.

Six of the British Museum’s Greek galleries, including the museum’s display of the Parthenon Marbles, have been closed for almost ten months, prompting concerns from Greek officials and campaigners that wet and damp could damage the ancient artworks.

The museum was forced to close on 16 December 2020 when a national Covid-19 lockdown was put in place. It reopened on 17 May 2021, but some of its Greek galleries remained closed due to ‘essential repairs’.

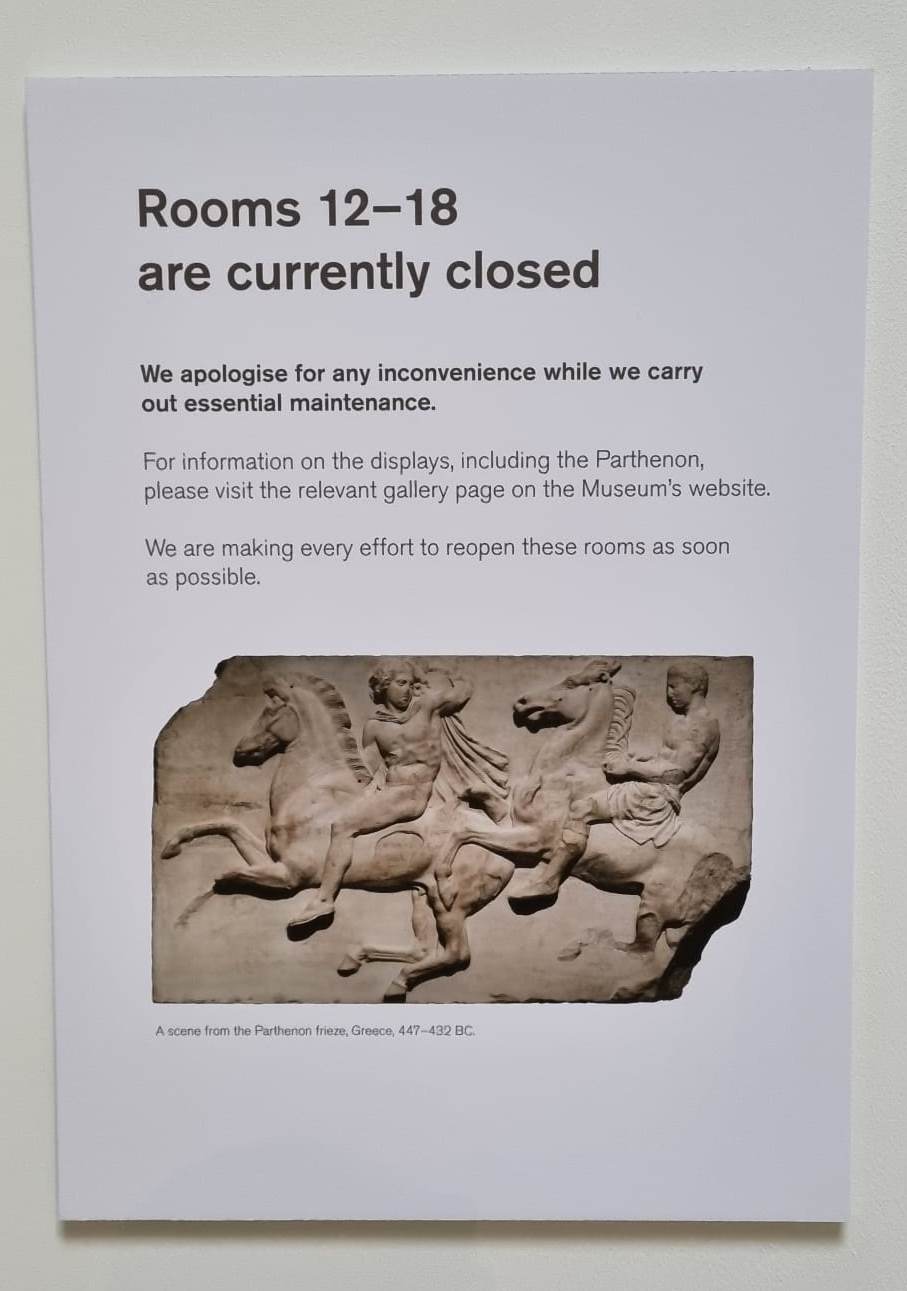

Ta Nea Greek daily newspaper visited the museum last week and confirmed that a total of six galleries of Greek art have yet to reopen; Rooms 15, 16, 17 and 18 are closed due to "maintenance"; Rooms 19 and 20 are closed to "comply with social distancing measures".

The Duveen Gallery (Room 18) which houses the Parthenon Sculptures, has been closed since December 2020.

Its leaky roof has made news many times before.

In December 2018, the glass roof of Room 18 began leaking after heavy rainfall in London. Witnesses reported seeing water dripping just centimetres away from the west pediment figure of Iris. More recently, leaks were caused by a heavy rainfall on July 25th that flooded central London.

The Greek government as well as campaigners for the reunification of the Parthenon Marbles have expressed concern about the poor state of the rooms.

On August 15, the International Association for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures (IARPS), which represents 21 national committees around the world, wrote to the British Museum Chairman Sir Richard Lambert, its Director Dr. Hartwig Fischer and its Trustees. To read the letter, follow the link here.

A copy of the letter was also sent to Prime Minister Johnson, the newly appointed Chair of the Trustees, George Osborne and the then Secretary of Culture, Oliver Dowden.

It said that “the planned reopening of the Greek rooms, postponed ‘until further notice’, after months of lockdown, is a deep worry,” adding that the “possible humidity problem (creates) a dangerous condition for the sculptures”.

It also called on the Museum to "reconsider its viewpoint on the continued division of the Parthenon Sculptures", noting that “there is a moral obligation to return and to reunify all the surviving Parthenon Sculptures in the Acropolis Museum with a direct visual contact to the Parthenon”.

"It is saddening that Room 18 has been closed ‘until further notice’," IARPS President Dr Christiane Tytgat told Ta Nea, adding that "the inappropriate climate conditions in the room are upsetting".

"I hope," she said, " that we do not have to wait another 22 years before we can admire the Parthenon Sculptures on display in London again, as it happened before, when the Duveen Gallery was hit by a bomb in 1940 and reopened only in 1962! Even if the Sculptures were then stored in a safe place and undamaged."

Almost two months later, the Museum has not responded to the letter, which Dr. Tytgat described as "sad."

Dame Janet Suzman, Chair of the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles (BCRPM), told Ta Nea: “I would be a happy person if Room 18 were permanently closed because those spectacular sculptures taken by the marauding Lord Elgin deserve to be reunited in the Acropolis Museum. No one can say for certain what remedial work is being done in the Greek galleries of the British Museum or for how long. The lack of climate controls in an old building are self-evident and has been questioned by BCRPM on other occasions: blow-heaters in winter, open exit doors in summer, leaking roof during the rainy season.”

“We urge the British Museum to stop repeating by rote the same mantra and to reunite those emblematic marble figures in the superlative Acropolis Museum, which has been built to the latest standards and allows visitors to view them in context with the Parthenon,” she added.

Professor Paul Cartledge, Vice-Chair of the BCRPM and Vice-President of the IARPS, told Ta Nea that he has found “the Trustees' failure to respond at all to the letter deeply disappointing - not at all the way to begin dialogueon this pressing cultural issue in a way fitting of its importance. Dismissing this very specific request is tantamount to not understanding the importance of cultural diplomacy. Time for the British Museum and the UK to join the 21st century, although it would have been good and great if they were to lead the way.”

Closed ‘until further notice’.

The website of the British Museum states that the Greek galleries are "closed until further notice", due to "regular maintenance works".

UNESCO recently expressed “concern that the Duveen Gallery of the British Museum is not currently open to the public due to essential repairs”, adding that it “looks forward to its reopening in due course.”

In his interview with Ta Nea, in January 2019, the director of the Museum, Dr. Hartwig Fischer, claimed that there was "a tiny leak" (in Room 18’s roof) which was “fixed right away ".

Lina Mendoni, Greece’s Culture minister has said that the conditions for exhibiting the Parthenon Sculptures at the British Museum “are not only inappropriate, but also dangerous”.

A British Museum spokesperson told Ta Nea that “there has previously been some water ingress in some gallery spaces closure”, adding that “there is no confirmed date for their reopening, but we are working towards later this autumn.”

The British Museum’s comment to Ta Nea in full:

“The Museum is an historic and listed building and there are ongoing infrastructure assessments across the site. We have a team of specialists who make regular checks across the Museum to monitor and ensure appropriate management of risks to the collection. The care of the collection and the safety of our visitors and staff are our utmost priority.

“The essential works being undertaken are part of a programme of building maintenance and conservation which will help enable future works on the Museum estate. Alongside these essential repairs, we are developing a strategic masterplan to transform the British Museum for the future. It will involve actively renovating our historic buildings and estate, improving our visitor experience and undertaking an ambitious redisplay of the collection in the years to come.

“Galleries 14 to 18 on the ground floor have been temporarily removed from the public access route. The Museum has undertaken a programme of work within these galleries and the scheduling of this work was delayed due to the impact of the pandemic on the Museum’s programme.

“Further works and surveys were undertaken this summer and these galleries are currently closed to ensure the safety of our visitors and the collection whilst these surveys are carried out. There has previously been some water ingress in some gallery spaces closure.

“There is no confirmed date for their reopening, but we are working towards later this autumn.”

Images below showing the closed door that has been temporaily erected across the entrance of Room 23 of the British Museu's Greek galleries. With a notice explaining that Rooms 12-18 are closed. Some of the galleries are closed for social distancing purposes with others closed for maintenance.

Photo credit: Yannis Andritsopoulos, London Correspondent for the Greek daily newspaper Ta Nea, 09.10.2010

Dr Tom Flynn's tweet below echoes the thoughts of many millions across the globe that support the reunification of the Parthenon Marbles: