Boris Johnson has long hailed Pericles as his political hero. How does the British Prime Minister compare to the ancient Athenian statesman?

For Professor Paul Cartledge, it’s straightforward: “Johnson and Pericles? No comparison. Johnson v Pericles? No contest,” he says.

The Cambridge classicist has spent more than 50 years studying the history and civilization of ancient Greece. An eminent Hellenist, a prolific writer (he has written, edited or co-edited more than 30 books) and a long-standing philhellene (he has been visiting Greece since 1970 and he is a staunch supporter of the Parthenon Marbles’ reunification), Cartledge will on Monday be named Commander of the Order of Honour (Ταξιάρχης τοῦ Τάγματος τῆς Τιμῆς). It is one of the highest honours that the Greek state awards. The decision to bestow the title on Cartledge for his “contribution to enhancing Greece’s stature abroad” was taken by Greek President Katerina Sakellaropoulou.

Cartledge has contributed to several television and radio programmes and publications on issues related to ancient Greece.

The renowned academic is author of popular history books such as The Spartans: An Epic History, Thermopylae: The Battle that Changed the World, The Greeks: A Portrait of Self and Others, Alexander the Great: The Hunt for a New Past and Democracy: A Life. His latest book is Thebes: The forgotten city of Ancient Greece (Picador, 2020). In 1998 he was the joint winner of the Criticos (now London Hellenic) Prize for The Cambridge Illustrated History of Ancient Greece.

Cartledge, 74, is A.G. Leventis Professor of Greek Culture emeritus at the University of Cambridge, A.G. Leventis Senior Research Fellow at Clare College, University of Cambridge, and Member of the European Advisory Board of Princeton University Press.

He is Vice-Chair of the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles (BCRPM) and elected Vice-President of the International Association for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures (IARPS). He is also President of The Hellenic Society, Chair of the London Hellenic Prize, member of the International Honorary Committee of the Thermopylae-Salamis 2500 Anniversary framework and Honorary Citizen of Sparta.

In an interview with Greek daily newspaper Ta Nea, Professor Paul Cartledge spoke about his relationship with Greece, ancient history (including its connection and relevance to our times), democracy (ancient and modern) and the Parthenon Marbles.

Q: Greek President Katerina Sakellaropoulou has named you Commander of the Order of Honour in recognition of your contribution in enhancing Greece's stature abroad. What does it mean to you to receive this award?

A: It means the world to me, since it's a public and visible confirmation that somehow both my academic research (and publications) and my attempted media interventions on cultural and other issues affecting modern as well as ancient Greece have been to a satisfactory degree successful. I see myself, perhaps rather grandiosely, as a 'public intellectual', and since around 1990 I have both tried to publish work that, though academically based and scrupulously researched, is also 'accessible' to a wider public than just my specialist university colleagues and students, and to intervene on major public cultural issues, such as the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles, a cause very dear to my heart. I tried to sum up these points as part of my Inaugural Lecture as the founding A.G. Leventis Professor of Greek Culture in the University of Cambridge (delivered 2009, and published by the C.U.P., 2009): 'Forever Young: Why Cambridge has a Professorship of Greek Culture'.

Q: When did you first become interested in Greek history and culture? Why did you choose to study the Classics?

A: I can almost pinpoint the moment to a precise year: I was given for my 8th birthday (1955) a copy of a simplified, children's version of Homer's Odyssey. We all know the famous episode when Odysseus, after 20 years away, at last returns to his island-kingdom of Ithaca, only to find that his palace has been taken over and is being trashed by 108 'suitors' (of his faithful Spartan wife Penelope). Outside the palace back door, full of ticks and generally in a very bad way, lies amid the dirt and squalor a dog - Argos. Once he had been Odysseus' favourite hunting dog, but now he is abandoned and degraded. Odysseus comes upon him and, though he is in disguise as a poor beggar man, Argos recognises his master! But the effort is too much - Argos has a heart attack and dies. Odysseus secretly sheds a tear - I wept out loud for half an hour...

That's the symbolic moment of origin of my classical career. Just as crucial, obviously, was the fact that I attended private schools in which the teaching of Latin was begun at the very same age - 8, and of Greek at age 11. And the learning of Latin and Greek was privileged: if you were good at these languages, as I was, then you found yourself placed in the 'top' forms or sets. And so it went, as I progressed from Colet Court in London to the senior St Paul's School, a famous Classics school founded in 1509 by humanist John Colet, a friend of Erasmus. And from there on to New College Oxford, to read 'Mods' and 'Greats', i.e. Classics (1965-69). I graduated with a 'Double First' and, since by 1969 I'd decided I wanted as a career to teach ancient history at university, I embarked on a course of doctoral (DPhil) research into early Spartan history and archaeology under the supervision of John Boardman - then plain 'Mr Boardman', now 'Sir John'.

Q: When did you first visit Greece and what do you recall from your first visit to the country?

A: I am rather ashamed - retrospectively - that I did not visit Greece until 1970 - as part of my doctoral programme. My first serious venture on Greek soil was on Crete, to take part in (in fact oversee the pottery shed for) Hugh Sackett & Mervyn Popham's excavation for the BSA (British School at Athens) of the so-called Unexplored Mansion site at Knossos. Mainly Roman levels were what we were hitting in summer 1970 - but that's not all we British and American students were hitting, by any means. A couple of local mpouats (boîtes) engaged our interest of an evening, and at weekends we went on ekdhromes, expeditions, either solo (as I did once - and when I asked directions, a local farmer asked me very fiercely 'Germanos eisai?' 'Oxi, Anglos!', I replied. Huge smiles all round - this was only a generation after the Nazi occupation) or in a group.

Participation in that excavation gave me a series of lasting and deep friendships, some now interrupted by distance or death but others still alive and well. It was also my introduction to Greek politics - under the 'dictatorship' of 'the Colonels'. Members of the BSA were required - by the Greek state - to swear that they wouldn't get involved in any political activity. I duly signed, but did not abide by my oath, not on Crete (where I listened and learned to how the fiercely independent Cretans saw Athens, regardless of which regime held power there) so much as back in Athens.

I signed the oath at the British School under the watchful eye of the then Director, Mr PM Fraser (All Souls Oxford). That would have been in about June 1970, when I arrived in Greece for the very first time. On Crete (BSA dig at Knossos) in summer 1970 I talked a lot of politics - the Cretans I spoke with (workers on the dig) were openly contemptuous of the Colonels. (Except for the Dig Foreman, Andonis - who was a Colonels' supporter. He had gained the position because his brother, a communist, had been sacked from it...) We weren't supposed even to 'talk' politics. Back in Athens in 1971 I had friends who were part of the underground resistance. e.g. I attended with them a 'secret' talk given by Cambridge economics prof Joan Robinson and went around with them distributing resistance literature to private addresses in the city. (No mobile phones, no internet...). On one occasion I agreed to act as a courier - between the resistance and (Lady) Amalia Fleming, widow of Sir Alexander (discoverer of penicillin), who lived in London. I was given - I can't now remember by whom - a fairly large packet (no idea what it contained!) to take through customs at Athens airport and then on to London, where I mailed it to Lady Fleming through the normal post. I was very very nervous going through Athens airport security and customs - but my carry-on bag wasn't searched.

Q: In Greece we have debates from time to time about the usefulness of studying Ancient Greek. Do you think that there is value in learning this ancient language?

A: I could hardly say 'no', could I? Let me start from the fact - I believe it is one - that the Greek poetic tradition is the longest continuous poetic tradition in the world, barring only - possibly - the Chinese. From Homer to the present day. One easy way of assimilating this is through The Penguin Book of Greek Verse, expertly edited and translated in 1971 by Constantine Trypanis. There are other such compendiums, but that one has the original Greek versions as well as a serviceable English (prose) translation. Then there is the fact - of this I have no doubt - that ancient Greek is the richest member of the Indo-European language family, capable of expressing the minutest nuances of emotion and description, blessed with several voices and moods and declensions and conjugations... Then - and directly consequent upon that latter fact - it's a fact that, if you don't know Greek, you can't speak a whole slew of English: so many are the loan words or invented words taken from Greek into English - e.g. photography ('light-writing/drawing') or xenophobia ('fear of strangers/foreigners/outsiders'). But of course, the chief value of learning ancient Greek is to read ancient Greek texts in the original - Homer, the world's greatest epic poet, Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, some of the world's greatest tragic dramatists, Hippocrates, father of Western medicine, Herodotus and Thucydides, founding fathers of my own discipline of History, Plato and Aristotle, twin founders of Western philosophy - need I continue??

Q: Britain has a rich tradition over many centuries in teaching and studying the Classics – from which you have benefited and to which you have contributed immensely. Why would someone study ancient history now? How is it relevant to us?

A: In my last answer I mentioned my intellectual roots in ancient Greece: the Histories of Herodotus of Halicarnassus (c. 484-425 BCE), the History of the Atheno-Peloponnesian war by Thucydides of Athens (c. 460-400). Most people who become professional classicists do not become as I did ancient historians; for them, the literature or the philosophy are what attract and engage them. But - like one of my own English history heroes, Edward Gibbon - I have known from the age of 8 or so that I wanted to be a historian, and, since I'm a Classicist, that means I'm an 'ancient' historian. But I insist: I am a historian who happens to specialise in ancient (Graeco-Roman, Mediterranean) history, not some peculiar species of historian. Like Herodotus what engages me above all are causality and causation - why did things happen, and happen the way they did, and in no other way? I mean really significant things such as the birth, development, spread and demise of (ancient, direct) democracy, the conquest of Greece by Republican Rome, the fall of the Roman Empire in the West and East. Like Thucydides, I'm particularly preoccupied with trying to understand and explain politics - the political process, the methods of politicians, the involvement of the masses in decision-making.

Q: Which ancient Greek figure stands out for you, and why?

A: May I choose two, please? One female, one male. My female choice is a Spartan, not just any Spartan female, I admit, but a princess of the blood (more precisely, of the Eurypontid blood). Sparta uniquely in the 5th and 4th centuries - still - had two royal houses, the senior males of which ruled as joint kings (basileis). Women in Sparta were unusually empowered, by contrast to the relatively lowly status of Greek women in others of the 1000 or so Greek cities. But even Sparta couldn't contemplate a ruling Queen. Nor - I am assuming - did wives choose the names of their daughters, so I am assuming that it was her father, King Archidamus II (r. c. 465-427), who chose the name of his daughter - my female choice - Kyniska. The name means 'little dog' or 'puppy', and it's the female equivalent of Kyniskos, a name attested elsewhere in the 5th-century Peloponnese. I infer that the name gives a nod to the fact that Spartans bred particularly excellent hunting dogs, especially females, which they used in pursuit of the greatest of all 'big game', the wild boar of the lower Taygetus mountain slopes. We don't know exactly when Kyniska was born - her full brother Agesilaus II saw the light of day in about 445, so I suppose that 440 or so would be a reasonable birthdate. In which case she was about 45 when she made the biggest possible splash in the world of sports normally restricted exclusively to Greek males: the equestrian competition at the Olympic Games. In 396 she won the top-notch 4-horse chariot race - and four years later repeated that amazing feat. And she was no shrinking violet. A statue base happens to have survived from Olympia on which Kyniska had engraved a boastful epigram, telling anyone who'd listen that she was 'the first woman in all Hellas (the Greek world) to have won this crown' - the victor's olive wreath. Of course, she hadn't actually driven the winning chariots, but she had reared and trained the horses in her own stables in Sparta, where there was a considerable number of successful (male) owners and trainers already. So just to ram the point home, she opened her epigram by stating her own aristocratic breeding pedigree and bloodline: 'kings are my father and brothers', that is, the aforementioned Archidamus II and Agesilaus II and her half-brother Agis II. By 396 both Archidamus and Agis were dead: how well did Kyniska's boast go down with her full brother, reigning co-king Agesilaus? Not well at all, I think. Agesilaus's encomiastic biographer, the Athenian Xenophon, took time out to insist that, although Kyniska had indeed won an Olympic victory, it was Agesilaus's idea in the first place that she compete at all, and anyway rearing race-horses was far less important than rearing war-horses!

My male choice is a different kettle of fish altogether: not a Spartan - nor an Athenian, nor a Syracusan, nor even a Macedonian but... a Theban. We don't know exactly when he was born, some time in the last quarter of the 5th century, nor do we know much about his family background or upbringing because - unlike that of his contemporary and sidekick Pelopidas - Epaminondas's biography by fellow-Boeotian Plutarch is lost. We assume he was high status and well educated, so his career and alleged espousal of Pythagoreanism would suggest. What we do know that, unlike Pelopidas again, who went into exile, Epameinondas remained in Thebes while it was under Spartan military occupation between 382 and 379 and did what he could to keep up Theban morale and resistance from the inside - until the daring stroke of Pelopidas and a small band of brothers effected Thebes's liberation in winter 379/8. Thereafter Epaminondas was in the frontline both physically and morally. On three fronts mainly: 1. the field of battle - he was a strategist and tactician of genius, winning for Thebes and its allies two major battles, Leuktra (371) and Mantineia (362); 2. federalism: Thebes was itself the chief city of a - moderately - democratic federal state, the Boeotians; in the 360s Epameinondas extended that principle to the Peloponnese with the foundation of Megalopolis as capital of the federal state of the Arcadians; and, not least, 3: liberation: in 369 Epameinondas was key to liberating the Helots of Messenia, Greeks who for centuries had been the unfree compulsory labour-force of the Spartans. Nor was he unconventional only in religion; so too in his private life. He never married, and he died (on the battlefield of Mantineia) and was buried side by side with his current male lover.

Q: In your recently released book Thebes: The Forgotten City of Ancient Greece you write that democracy in ancient Greece "was not just a matter of institutions but also a matter of deep culture". What do you mean by that and, given recent political developments in several parts of the world, is democracy still deeply ingrained in our culture?

A: I'm almost inclined to say that the difference between any ancient form of democracy and any modern version is like the difference between chalk and cheese, or apples and pears... All ancient versions of demokratia were direct - in antiquity 'we the people' (demos) did not merely choose others to rule for/instead of them but ruled directly themselves. That in itself gave ancient Greek democratic citizens - free, legitimate adult males only, of course - a participatory stake in governance that is not available to the vast majority of citizens in representative democratic systems like our own today. That participatory stake was not felt or exercised only occasionally but almost on an everyday basis: in the 4th century BCE the Athenian Assembly met every 9 days, yes, really, the decision-making organ of the Athenian democratic state made major decisions of religious and other political policy every 9 days. The 6000 citizens who put themselves forward to be enrolled, by lot, on the annual panel of jurors might sit on average every other day - for which they were paid a small fee out of state funds. Every year the Athenians staged two religious play-festivals, for which audience members who were too poor to afford the entrance fee to the Theatre of Dionysus were given a small subsidy. Decisions as to who were the winning playwrights and impresarios - the ancient Athenian Oscars - were made by democratic majority vote. All that implies that democracy was for them not just a matter of institutions but also a matter of deep culture. That implication was made manifest in the second half of the 4th century when a new goddess was added to the official Athenian democratic pantheon, the personification of none other than Demokratia, herself.

Q: The title of a BBC Radio 4 series you recently participated in was Could an ancient Athenian Fix Britain? What is the answer to that question? And, do you think an ancient Athenian could fix modern Greece as well?

A: There is no answer to that question! I mean, no answer to 'how could or should Britain be fixed?', if by that is meant - how do we overcome the utterly disgraceful and shameful class divide between rich and poor (which in Covid-ridden Britain equates pretty much to healthy and unhealthy Britain)? or between the well and the less well educated? or between the rich and poor regions of not just England but also Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland? or between those regions - in favour of the strengthening or shoring-up of our now very shaky Union? I could go on. The ancient Athenian polis and the modern British state are simply not commensurable. However, at another level, there are ways in which, it could be suggested, ancient Athenian practices - I mean democratic political practices - could and should be re-evaluated with a view to seeing whether and how they might improve our own. Take the present - unelected - House of Lords: scandalously un-democratic as such (and that's without mentioning the 80-plus 'hereditaries'!!). And what about having far more in the way of genuinely democratic input into legislation - via constitutional assemblies of bodies selected by lot to be genuinely representative of all relevant sections of society, who would then put forward measured recommendations to Parliament? What about genuinely democratic referendums or plebiscites - in which all parties to a debate have to put forward a manifesto for which, if they win, they will be held responsible and accountable, if necessary through the courts?

Q: Boris Johnson, the British Prime Minister, has made no secret of his classical education and love for Greece. He has also said that Pericles is his hero. Do you see any similarities between the two statesmen? What is your opinion of Mr Johnson?

A: I am an academic, not a politician, but I am also a committed citizen, and not a supporter of the Party that chose Mr Johnson as its leader and thereby - at a stroke - originally as our Prime Minister. Very undemocratic, that. The office of the UK Prime Minister has infinitely more discretionary powers than Pericles ever held. Pericles was regularly elected to the top executive Athenian office, but he was as such a member of a board of ten, and any moment almost of any day he might be impeached - as he in fact was in 429 (deposed and fined). For ancient Athenian democrats, all officials however selected had to be made constantly to realise they were accountable - to the People. Johnson and Pericles? No comparison. Johnson v Pericles? No contest.

Q: In his recent interview with Ta Nea, Johnson said that “the (Parthenon) Sculptures were legally acquired by Lord Elginand have been legally owned by the British Museum’s Trustees since their acquisition.” I know that you have been campaigning for decades for the Marbles’ reunification. What did you think when you read his comments? Why do you think that the Parthenon Marbles should return to Greece?

A: How would a French person feel if the Bayeux tapestry were cut in half, and half were to remain in Bayeux, while the other half was transported to Berlin? How would an Italian feel if the Mona Lisa were cut in half and one half was transported and permanently housed in Milan while the other half remained in Paris? How would one feel about either of those - as a cultured European, or as a citizen of the world? What the British Museum currently holds of the Parthenon Marbles were removed when Athens was part of the Ottoman Empire, a power whose local functionaries on the spot could not give a fig for what Britain's Ambassador to the Sublime Porte, Lord Elgin, did to or with the Parthenon Marbles. There is no evidence yet discovered to prove that what Elgin in fact did (sheer vandalism, according to Lord Byron and many of us since) was literally authorised by the Ottoman Sultan. But, even if there were, so what? What - moral - authority could possibly legitimise the removal of artefacts from a building under alien control to the jurisdiction of a foreign power which then claims them as spoils by a supposedly legal enactment? There is in Athens on the Acropolis the very substantial remnant of a once aesthetically magnificent temple, the shadow of which extends from antiquity to modernity. There is in Athens a simply amazing modern Museum with a dedicated gallery intervisible with the Acropolis in which what the Greeks hold of the Parthenon sculptures are properly - I mean scientifically, art-historically correctly - displayed. Reunification? Q.E.D.

Q: Greece is celebrating this year the bicentennial of its War of Independence, as well as the 2,500th anniversary of the Battle of Thermopylae and naval battle of Salamis. How do you evaluate the historic importance of the War of Independence and do you agree that Thermopylae and Salamis were of seminal importance for the course of Western Civilisation as we know it?

A: I am a historian of ancient Greece and Rome, not of early 19th-century Greece and Europe - and by extension the world. But I have of course read widely in the accessible literature and am aware that there has been a ton of new research issuing forth especially since the 150th anniversary, in 1971, and now at the bicentennial. As I understand it, that research tends to emphasise the singularity, the crucially influential singularity, of what Greeks both inside and outside the boundaries of the Ottoman empire achieved during the crucial first three decades of the 19th century (not coincidentally precisely the period of Lord Elgin's vandalism). In short, the Rising of 1821 saw the birth of modernity, political modernity, both in Greece and elsewhere.

As for the 2500th anniversary - or rather the anniversaries in 2021 of the two battles of 480 BCE and the anniversary in 2022 of the finally decisive battle of Plataea in 479 BCE - the issue hinges on a massive 'what if?' What if the invading Persians under Xerxes had won, rather than the 32 or 33 resisting Greek cities? (And what if at precisely the same moment, in 480 BCE, the Carthaginians of north Africa had defeated Greek Syracuse and taken over Greek Sicily?) There are many imponderables here, and as a historian I have to insist first that we must not talk of 'Greece' or 'Greeks' as if they were a unitary political force in the way that 'the Persians' were. Most Greeks of the Aegean area did NOT choose to resist the Persian invasion, and many of them fought for rather than against the Persians. Consider only Thebes: rather than join Sparta and Athens, the leading resisters, Thebes sided with almost all Greeks from Boeotia to the Hellespont and took the Persian side. And it would be hard to find two Greek cities more UNalike than Sparta and Athens in 480-479 BCE. No doubt all the resisters agreed equally that they were fighting for freedom FROM a potential Persian takeover; but within Sparta and Athens 'freedom' could have very different meanings for different sectors of the population - for male citizens as opposed to female; for all citizens as opposed to legally unfree Helots or chattel slaves. So, for me, the question of what difference did the loyalist Greeks' victory over the Persians make on a grand, world-historical/civilisational scale boils down to - would the Athenians' precious and still infant democracy have been allowed to survive, had the Persians won? To which my answer is: unquestionably not. And - therefore - but for the loyalist Greeks' victory, there would have been no "Persians" tragedy by Aeschylus (472 BCE), and indeed no flowering of the tragic and later comic drama that constitutes the very foundation of all Western drama. No democracy would have meant no free speech, no free exchange of scientific and philosophical and other ideas, ideas which sometimes challenged even the very basis of conventional norms not least in religion. But even so, it is not of course the ancient Greeks or Athenians themselves who directly ensured that their original creations should influence subsequent civilisations including our own today - for that, we have to thank the Romans, the Byzantine Greeks, the European Renaissance, the European and American Enlightenments... 'Legacy' or cultural inheritance is a dynamic, two-way, dialectical and constantly renegotiable process - currently being rather fiercely debated so far as 'Classics' is concerned, along the two axes of racism and sexism above all. Let a thousand flowers bloom...

This interview was written by Ioannis Andritsopoulos, UK Correspondent for Greek daily newspaper Ta Nea and published on 17 April 2021

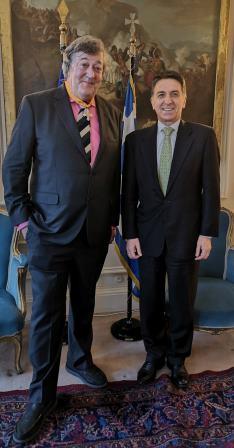

Professor Paul Cartledge received his Commander of the Order of Honour from H.E Ambassador Ioannis Raptakis in London on 22 April 2021, at the Ambassador's Residence . This was organised on the occasion of Philhellenism and International Solidarity Day and Greece's 1821 Bicentennial. John Kittmer, Kevin Featherstone, Stephen Fry and Robin Lane Fox were awarded the Commander of the Order of Phoenix and Professor Paul Cartledge with the Commander of the Order of Honour . H. E Ambassador of Greece, Ioannis Raptakis, presented the medals on behalf of the President of the Hellenic Republic, Katerina Sakellaropoulou, recognising each distinguished philhellene for their contribution in enhancing knowledge about Greece in the UK and reinforcing the ties between the two countries.

H.E. Ambassador Raptakis with Professor Cartledge, awarded the medal of Commander of the Order of Honour and second photo John Kitmer with Ambassador Raptakis and Professor Cartledge.

Stephen Fry with Ambassador Raptakis, second photo Ambassador Raptais with Kevin Featherstone and last image is Lane Fox.