In the British Museum’s statement on the Parthenon Marbles, we come across the familiar claim of the legality of Elgin’s acquisition. ‘Lord Elgin’s activities,’ we read, ‘were thoroughly investigated by a Parliamentary Select Committee in 1816 and found to be entirely legal.’ Simple, succinct, almost convincing, this is the only legal argument in the Museum’s arsenal against repatriation. But is it true?

In early 1816, shortly after Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo and the return of his European loot, a parliamentary select committee was formed in London to evaluate Elgin’s request for the British government to buy his collection of marbles and other antiquities. The committee was assigned two tasks: to determine whether the government should acquire the collection, and to assess its monetary value.

Not being a court of justice, the select committee did not have the authority to decide questions of legality – not in the sense that those of us in the legal profession understand ‘legality’. Its official mandate did not explicitly include investigating the lawfulness of Elgin’s actions, although, ultimately, the committee did raise the question as an incidental concern. Did Elgin have permission to remove the Marbles?

The ‘firman’ that was not

Elgin claimed that he had obtained authorisation to carry out the removals. No original proof has ever been produced of that authorisation, the famous ‘firman’ that, if it existed, was not a firman at all (both Dr Philip Hunt, Elgin’s right-hand man, and its presumed Italian translation described the document as a ‘letter’).

At first, the select committee appeared to try to corroborate Elgin’s claim. Did Elgin have a document in his possession attesting permission? He didn’t. If someone had such a document, Elgin said, it would be his agent, Giovanni Battista Lusieri, who was still in Athens, or it would be the local Ottoman authorities in Athens. William Richard Hamilton, Elgin’s private secretary, had a more interesting story: when asked whether he knew anything about the permission, he admitted that he had no personal knowledge of the matter! But let us leave Hamilton aside. Elgin contended that surely the (written) permission must be in Athens. Now one expects that, to conduct a thorough investigation, the committee would need to send to Athens for Lusieri and the local authorities to look there for some proof of the ‘firman’ that was not. How else could the select committee, acting in good faith, decide the matter?

Yet, the committee showed no willingness to make the effort. In its report, it stated:

'The Turkish ministers of that day are, in fact, the only persons in the world capable (if they are still alive) of deciding the doubt; and it is probable that even they, if it were possible to consult them, might be unable to form any very distinct discrimination as to the character in consideration of which they acceded to Lord Elgin’s request.'

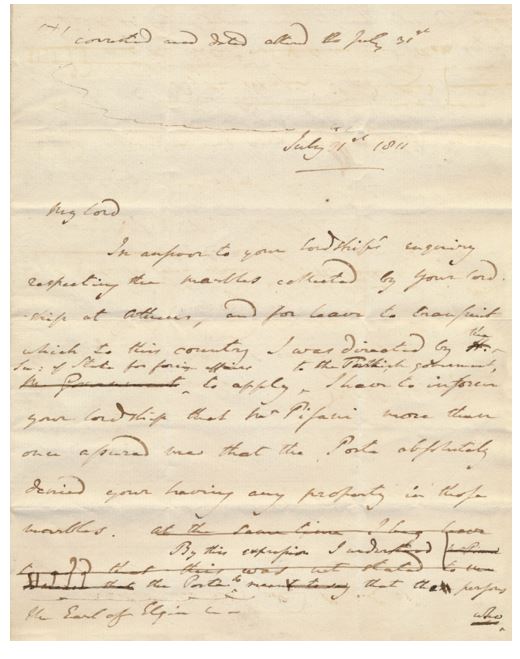

If they were still alive? If it were possible to consult them? The Sultan (the one with the authority to sign firmans) was still alive, and it would have been easy to consult him. The British government had an ambassador in Constantinople (Sir Robert Liston) – why not ask him? And why not call in as witness a former British ambassador to the Sublime Porte who openly affirmed that the Ottomans categorically denied Elgin’s ownership of the marbles? On 31 July 1811, Sir Robert Adair informed Elgin that ‘the Porte absolutely denied’ that he, Elgin, had ‘any property in those marbles’.

‘… the Porte absolutely denied your having any property in those marbles.’

Robert Adair’s draft letter to Elgin (31 July 1811). Collection of Theodore Theodorou. Used with permission. For a full transcript, see http://www.adairtoelgin.com.

It was not the first time that Adair shared this knowledge. In April 1811, the Speaker of the House of Commons, Charles Abbot, 1st Lord Colchester, recorded in his diary that Adair ‘was expressly informed by the Turkish Government that they entirely disavowed ever having given any authority to Lord Elgin for removing any part of his collection’. Even Elgin repeated, in an 1811 letter to the then prime minister, Spencer Perceval, that he did not lawfully own ‘his’ collection. People in government were fully aware of the fact that Elgin did not have permission to act as he did.

When the task was to persuade the Ottomans to permit the shipment of the part of Elgin’s collection that had remained in Athens, the government exerted pressure on both its ambassador (Adair at the time) and the Turkish officials. But when it came to determining whether Elgin had permission to act as he did, the select committee forgot it had a British ambassador (Liston) and appeared to hope that the Turkish officials were dead. Better let sleeping dogs lie. The committee took Elgin’s word and entirely ignored the fact that everything other than milord’s own impression pointed to the absence of permission.

The corruption

Then there was the issue of corruption. The select committee had Elgin’s admission of bribes. A list of his expenses incurred to procure the Marbles was published as an annexe to the select committee report. In it, we learn that Elgin paid 21,902 piastres (about £157,500 today) for ‘presents, found necessary for the local authorities, in Athens alone’. To grasp the significance of this sum, let us recall that, when parliament ultimately purchased the marbles, it paid Elgin a mere £35,000 (equivalent to about £4 million today). Corruption we assume just ‘happened’ in the Ottoman empire. But did it also ‘happen’ in Great Britain? Elgin was not an ordinary traveller in the Ottoman empire; he was the British ambassador, a representative of the Crown. Corruption was an offence in England and had been illegal since the time of the Magna Carta. Throughout the 18th century corruption was a crime punishable by English law. In the realm of electoral law, to bribe a voter had been an offence since the 1690s.

That bribes were a relevant legal consideration is also evident from the heated parliamentary debate on the corruption involved in obtaining the Marbles at the time. The acquisition was so inexplicable that some MPs even regarded it as a bribe to Elgin, and MP Preston remarked that, if ambassadors were allowed to get away with what Elgin had done, many would come back home as ‘merchants’. Yet the select committee did not act on the knowledge of the corruption.

The unpalatable truth is that the committee was expected to arrive at a predetermined conclusion: the Marbles should be bought for the nation. The absence of any statement in the committee’s report regarding the legality of the acquisition is significant. The committee repeated statements made by Elgin and his agents as if they reflected the truth. But never did it offer its own express conclusion that the acquisition was lawful. Nowhere in the select committee report do we find the committee’s opinion that Elgin’s actions were ‘legal’ – let alone ‘entirely legal’.

Catharine Titi

Catharine Titi is a tenured Research Associate Professor at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) and author of 'The Parthenon Marbles and International Law' (Springer 2023).