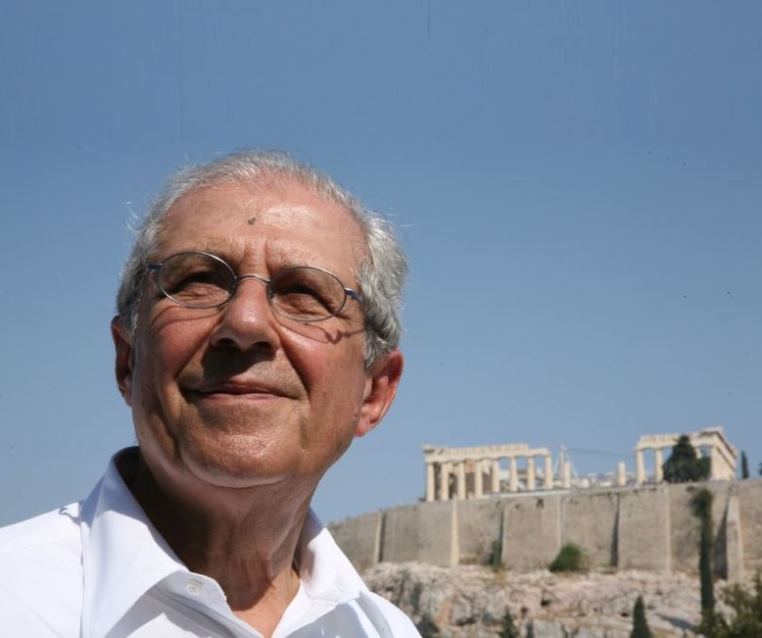

Professor Dimitrios Pandermalis (1940-2022)

On 14 September 2022, the Acropolis Museum lost a loved one: Dimitrios Pandermalis, Emeritus Professor of Classical Archeology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. His greatest contribution was the creation of the Acropolis Museum, serving as Chairman of the Board of Directors of the New Acropolis Museum Construction Organization from 2000 to 2019 and as Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Acropolis Museum from 2009 to 2022.

The Acropolis Museum contains not only the beauty of the ancient Greek world but also the soul of its creator and we will always remember him with love and gratitude. The Museum held a 40-day memorial service at the Holy Church of Agios Georgios and Agioi Anargyros Makrygianni and on the same day an olive tree was planted in memory of its late President, which welcomes visitors at the entrance of the Museum on Mitsaion Street.

The Museum's Board of Directors named the Amphitheater after its late President and instituted the "Dimitrios Pandermalis" Classical Archaeology Scholarship Programme. For the anniversary of the Acropolis Museum, on Tuesday, June 20, 2023, the Youth Orchestra of Dion will offer visitors a free musical tribute to Greek poetry set to music, respectively dedicated to the memory of Prof. Dimitrios Pandermalis.

Artistic events and collaborations

Over the last two years, the Museum has offered its visitors a multitude of artistic events and experiences:

• Dance performances in the exhibition spaces in collaboration with the National Opera (MicroDances Athens, 9-10 October 2021).

• A musical evening for International Women's Day in the Parthenon Hall with the theme "The strange goddesses of the Parthenon" and a presentation of the work of poets of antiquity, with music by Lena Platonos and interpretation by Maria Faradouri, a collaboration with the Marianna V. Vardinogianni Foundation (08 March 2022).

• Musical events in the forecourt of the Museum with the participation of well-known performers, such as Natasa Bofiliou, in the context of the 1st Worship Music Festival, a collaboration with the Ministry of Culture & Sports and the National Opera (18-20 April 2022).

• Rachmaninoff Tribute in the Parthenon Hall, as part of the "Chamber Music in Museums" programme, in collaboration with the Athens State Orchestra (31 March 2023).

The Museum started a new collaboration with the Development and Tourism Promotion Company of the Municipality of Athens with its participation in the Athens City Festival, where it organized two tasting evenings in the restaurant combined with a guided tour of the exhibits related to ancient nutrition (12 May 2022 and 4 May 2023) and two jazz concerts on the restaurant terrace (16 May 2022 and 22 May 2023).

On the August Full Moon, the Museum offered its visitors an evening of Greek songs about the moon and film music by the Air Force Band (12 August 2022). During the festive season of Christmas, the Museum presented carols by the Children's Choir of the National Opera (22 December 2022) and the Women's Vocal Ensemble CHORES (28 December 2022), two events were held in collaboration with the National Opera. It also hosted the famous Wind Orchestra of the Music School of Ilium (19 December 2021) and, for traditional dances, the Rethymno Coat Dressers' Club of Crete (23 December 2021) and the Episcopal Club of Naoussa, Imathia Prefecture (30 December 2022).

Original thematic presentations

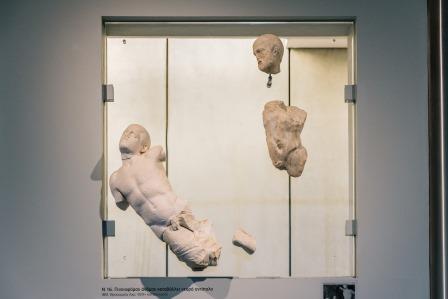

The Museum continues to offer free weekly themed presentations by its archaeologists, giving visitors the opportunity to discover interesting, often unknown, aspects of the ancient world. On the occasion of the action "Periodic or unexpected visitors" with works from Canada and the USA, the presentations "A celebration for Athena. The procession and games of the Great Panathenaians" (24 June 2022 - 21 April 2023) and "The world of work in ancient Athens" (05 February 2023 - 30 July 2023). In the presentation "Hidden Histories of Dispersion" (22 May 2022 - 29 January 2023), visitors discovered the adventures of smaller fragments of the Parthenon's sculptural decoration, beyond the sculptures found in the British Museum, but also of other Acropolis antiquities that are now scattered in other European museums.

At the same time, the themed "Saturday at the Museum with 20+1 masterpieces" continues until today, a special walk through the exhibition spaces that introduces visitors to ancient Greek art through myths and legends, beliefs and traditions, historical landmarks and human stories. During the summer months, the presentation "Walking in the ancient neighborhood of the Acropolis Museum", a fascinating journey through time, history and the daily life of the people who lived in the shadow of the Acropolis rock for more than 4,500 years, is offered. Visitors had the opportunity to attend this theme on 27-28 May 2023, in two extraordinary presentations as part of the pan-Hellenic anniversary event "Green Cultural Routes" organized by the Ministry of Culture and Sports.

Programmes for special audience groups

Responding to its role as a cultural organization at the service of society as a whole, the Museum implements actions and programs aimed at special groups of visitors, contributing to their social inclusion and reintegration. The Museum included in its activities regular programmes aimed at refugees and immigrants, encouraging their acquaintance and familiarization with the history and culture of the country that hosts them. At the same time, expanded cooperation with the Detention Centers of the country, offering online tours to groups of students of the second chance schools of the prisons, while carrying out programmes for special schools, structures for the treatment of the mentally ill and rehabilitation centers for people with addiction. In addition, collaboration with the Special Secretariat for the Protection of Unaccompanied Minors and the trainers of the Hospitality Structures for the planning and implementation of the inclusive action for unaccompanied minor refugees on the theme "Arts, craftsmen and professions in ancient Athens", which began in May 2023.

Schools

During the period June 2021 - June 2023, the Museum was visited by 139,740 schoolchildren from Greece and 92,802 schoolchildren from abroad. Many of them attended one of the 6 educational programmes offered by the Department of Educational Programmes. These programs are aimed at all levels of education, include attractive itineraries and are designed with modern museum-pedagogical concepts and an experiential approach. In addition, the Department offered another activity entitled "The 6th Grader at the Acropolis Museum" in collaboration with AMKE Aegea. For better communication between the Museum and schools, 2 seminars were organized for teachers of all levels of education entitled "Planning the visit to the Acropolis Museum" (25 November2022 and 09 December2022). For schools that are unable to visit the Museum, the Department of Educational Programmes recently created the "Museum in the School" programme, where schools can choose from 5 online programmes presented live by the Museum's archaeologists.

Particularly successful was the educational activity "Ironing at the Acropolis Museum", a collaboration with the neighboring 70th Primary School of Athens. On 25 November 2022, the students of the 4th grade gathered in the gardens of the Museum where the archaeologists spoke to them about the importance of the olive and its oil in ancient Athens. the agronomist gave the students important information about harvesting, and the children enthusiastically picked the olives from the olive trees of the Museum. Then, with the help of the educational materials provided by the Department of Educational Programmes, they prepared in the classroom, and took on the role of tour guides to presented to their parents those exhibits of the Museum that tell stories about the olive and the oil in ancient Athens (12 March and 02 April 2023).

Families

The Museum offered families with children a series of imaginative programmes. On the occasion of the theme "The Power of Museums" during International Museum Day 2022 (18 May 2022), digital applications for children and adults were presented in the Museum premises. On the occasion of the theme "Sustainable Heritage" during the European Days of Cultural Heritage, visitors watched the programme "In the houses of the ancients... without television and internet" (24-25 September 2022) at the Museum's archaeological excavation. During the festive season of Christmas, families participated in the programmes "Audio-narratives of strange divine births" (29 December 2021 - 30 December 2021) and "Goblin... confusions" (28 December 2022 - 05 January 2023), which continues with success until today with the "Strange Creatures at the Museum" programme. The above celebratory activities are carried out in collaboration with the Information and Education Department of the YSMA, which in addition carries out 3 school programmes at the Museum, including 2 seminars for teachers, and participated in the activity "The 6th Grade at the Acropolis Museum" in collaboration with AMKE Aegean.

Periodic reports

From 20 December 2022 until 02 April 2023, the Museum presented in the Hall of Periodical Exhibitions the exhibition entitled "Clothes of the Soul", with 70 emblematic works of the photographer Vangelis Kyris and the exponent of the art of embroidery Anatoly Georgiev. The exhibition, held under the auspices of A.E. of the President of the Republic Katerina Sakellaropoulou, was held with the kind support of the Marianna V. Vardinogianni Foundation and the cooperation of the National History Museum.

From 24 May 2023 through 04 June 2023, the Museum hosted the exhibition "A More Perfect Union: American Artists and the Currents of Our Time" organized by the US Embassy. in Athens in collaboration with the Art in Embassies programme of the U.S. State Department, under the auspices of the Ministry of Culture and Sports. The exhibition focused on issues of equality and freedom, with artworks by the most well-known contemporary American artists, including Bruce Nauman, Yoko Ono, Christine Sun Kim, Edward Ruscha and Carrie Mae Weems.

Unexpected visitors to the Museum

As part of the series of exhibition activities "Periodic or unexpected visitors", the Museum presented to the public works from other museums together with or independently of its exhibits. From 20 June 2022 to 23 April 2023, it hosted two fine art vases from the Royal Ontario Museum, Canada. These are two Panathenaic amphorae, the vessels that were filled with oil, and used to award prizes to the winners of the games of the Great Panathenaic festival. Their exhibition in the Parthenon hall gave them the opportunity to "converse" with the masterful frieze of the great temple, in which Phidias and his collaborators masterfully carved the Panathenaic procession of this Athenian celebration. As part of this exhibition, the Museum presented on 29 June 2022 a lecture by the Director of the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM), Mr. Josh Basseches, on the theme of transforming the museum experience at the ROM in the 21st century.

On 05 February, 2023, it welcomed three Attic pottery vessels from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA, with performances by artisans and professionals, which were placed in the new exhibition section "Officials and Professionals", in the Hall of the Ancient Acropolis, offering visitors a more complete picture of the of working people in ancient Athens. For "International Women's Day", he presented a work - a hymn to female beauty, "Venus in the Golden Bikini", a small statue depicting the goddess in stunning jewelry and a golden garment reminiscent of a "bikini". The work traveled from the National Archaeological Museum of Naples and was presented on the ground floor of the Museum from 08 March to 28 May 2023.

Documentation of archaeological collections

The Department of Archaeological Collections continues the documentation of the collections with research, new entries, explanations of terms (glossary), bibliographic references, photographs, and drawings of the 1,112 objects that are to be presented in the on-site exhibition of the Archaeological Excavation as well as for works of the Acropolis that are kept in archaeological warehouses. The documentation and posting on the website of the 63 copies of the sculptural decorations of the Parthenon that are in the British Museum, as well as other Museums, is complete, and currently preparation is underway to post the excavation objects as well. The purpose of posting on the website, in which 2,245 projects are currently registered, is to provide the general public with free access to the information on these artefacts. At the same time, the Museum published on its website the upgraded version of the online application www.parthenonfrieze.gr, with photos and descriptions of all the surviving stones of the frieze located in the Acropolis Museum and abroad. The upgrade of the application was carried out thanks to the excellent cooperation of the Museum with the Acropolis Monuments Maintenance Service, alongside the National Center for Documentation and Electronic Content-EKT.

Maintenance of exhibits

The Conservation and Casting Department completed the conservation or re-conservation work of 322 objects (sculptures, ceramics, metal and bone), with the main one being the conservation and change of the display method of the Kouros Akr statue. 596. Also, the cleaning programme with laser technology was completed, 3D scanning of exhibits was carried out and cleaning and maintenance work carried out in the excavation (floors, mosaics, frescoes and mortars). At the same time, the Department proceeded with the production of approximately 4,204 faithful replicas of Museum exhibits and scale replicas, and the application of high-precision patina with painted details to some of them. This production is made with the aim of making the copies available exclusively at the Museum's sales offices.

Renewal of the permanent exhibition

The continuous enrichment, and renewal of the permanent exhibition is for the Acropolis Museum is an important part of the museum's practice. For this reason, a series of corrective actions, mainly in the Hall of the Archaic Acropolis, are carried out in order to divide the exhibits into their thematic sections in a rational fashion. At the entrance of the renovated hall, the visitor is greeted by the two sphinxes of the Acropolis and immediately after the Musketeer. The concentration of the archaic architectural sculptures, the Maidens and the male statues in distinct sections - allows a better intake of the museum narrative and enhances the visitor's experience.

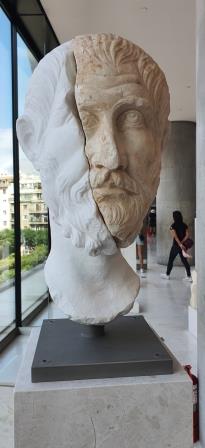

The new exhibition section "Officials and Professionals" was also created, enabling the visitor to see with a different eye, not only the aesthetic beauty of the statues, but also the works of art, the people and the societies that produced them. At the same time, the exhibition was enriched with new works. In the Hall of the Archaic Acropolis, Kouros Akr was repositioned. 596, after the re-conservation and alignment of the trunk with the base, and the base of the laundromat of Plyntria Smikynthes (Akr. 607), the column of Simon the Gnapheus (Akr. 429) and the column with the statue of the Maiden ( Acc. 6503). The head of Homer (EAM 626), the head attributed to the orator Dexippus (EAM 581) and the architectural member with the relief symbols of Athena (Akr. 2444) were added to the north wing of the first floor. In addition, the Museum proceeded to change the lighting in the exhibition spaces of the first and third floors, creating better viewing conditions and highlighting charming details of the exhibits.

the base of the laundromat of Plyntria Smikynthes (Akr. 607),

the column with the statue of the Maiden ( Acc. 6503)

the orator Dexippus (EAM 581)

The head of Homer (EAM 626)

Reunification of the Parthenon's architectural sculptures

On 29 September 2021, a UNESCO Decision was made for the first time after 38 years of recommendations, recognizing the intergovernmental nature of the Greek request for the reunification of the Parthenon architectural sculptures. On 03 January 2022, the National Archaeological Museum returned to the Acropolis Museum ten fragments of the sculptural decoration of the Parthenon. On 10 January 2022, the "Fagan fragment" was returned from the A. Salinas Museum in Palermo. On 02 May 2022, UNESCO unanimously ratified the September 2021 Decision. On 29 May 2022, a nulla osta was issued by the Italian Ministry of Culture for the "Fagan Fragment" to leave Italy forever, as it had already been accepted by the Sicilian Authorities. On 04 June 2022, the definitive reunification of the "Fagan fragment" took place on the east frieze of the Parthenon at the Acropolis Museum.

This action paved the way for the final return of three fragments of the sculptural decoration of the Parthenon from the Vatican Museums, thanks to the decision of Pope Francis on 16 December 2022 to donate them to the Archbishop of Athens. On 07 March 2023, in the halls of the Musei Vaticani, the text of the agreement was signed between the representative of the Pope, Cardinal Fernando Vérgez Alzaga, the representative of the Archbishop of Athens and All Greece, Father Emmanuel Papamikroulis and the Minister of Culture and Sports Dr Lina Mendoni. On the same day, the Protocol of Delivery and Receipt of the three fragments was signed by Archbishop Hieronymos II and the General Director of the Acropolis Museum, Prof. Nikolaos Chr. Stampolidis. The fragments arrived in Athens on 10 March 2023 and were reunited with the Museum's exhibit on 24 March 24 2023.

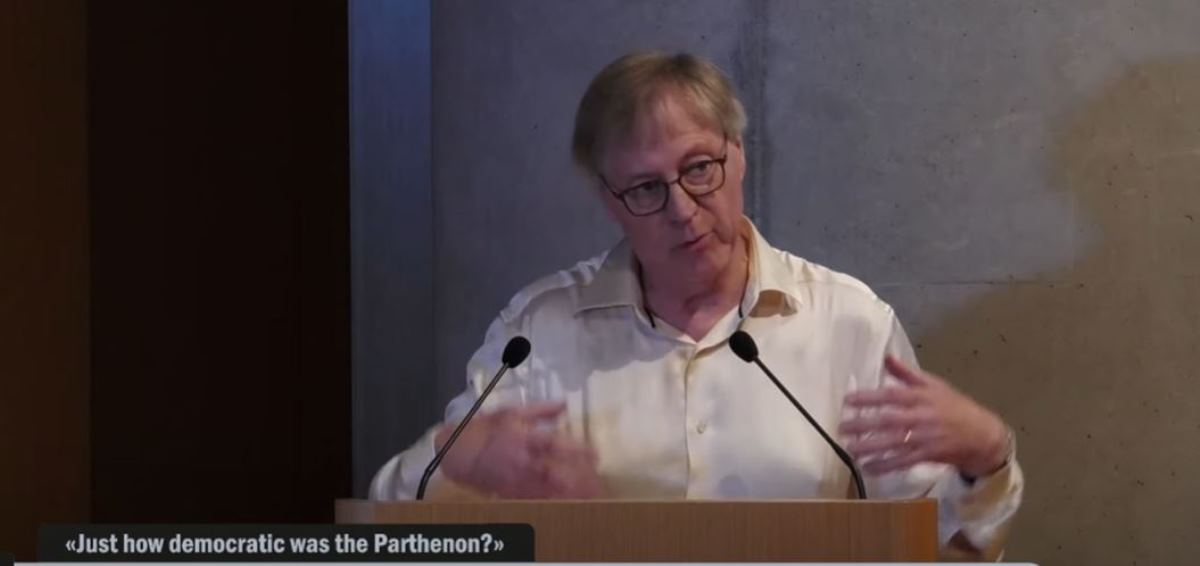

Finally, on the occasion of the General Assembly of the International Association for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures held at the Acropolis Museum on 15 September 2022, the Museum in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture, organised the international conference on "Parthenon and Democracy". Distinguished representatives of the international Committees for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures participated.

Professor Paul Cartledge as Vice-Chair of IARPS and BCRPM, delivered at this Conference on 16 September 2022, in the Pandremalis Auditorium of the Acropolis Museum, his presentatioon, which was aptly entitled: ‘Just how democratic (in what ways, to what extent) was the (original) Parthenon?’

Museum attendance

This two-year period was extremely important, as the operation of the Museum proceeded without interruption, taking into account the limitations created by the relevant health protocols. The total number of visitors to the Museum were as follows: 2nd Semester of 2021 there were 483,445 visitors, 1st Semester 2022 there were 567,951 visitors, 2nd Semester 2022 there were 884,583 visitors, 1st Semester 2023 there were 831,987 visitors.