The Figurine: When Beauty Inspires Crime

Victoria Hislop in conversation with David Wills at The Hellenic Centre, Marylebone

Tuesday 14th May, 2024

This was the first time I’ve attended the Hellenic Centre for a Marbles-adjacent event since BCRPM’s International Colloquy in 2012, though I do come here for the odd concert and my weekly language classes. 12 years ago, we heard the late human rights advocate George Bizos speak; on Tuesday there was a literary bent, before an audience ready to hear best-selling author (and BCRPM member) Victoria Hislop open up about her new novel The Figurine. At the top of the agenda were the places – namely, Athens and the Cyclades – and the crimes – cultural trafficking – that inspired it, in conversation with David Wills from the Society for Modern Greek Studies.

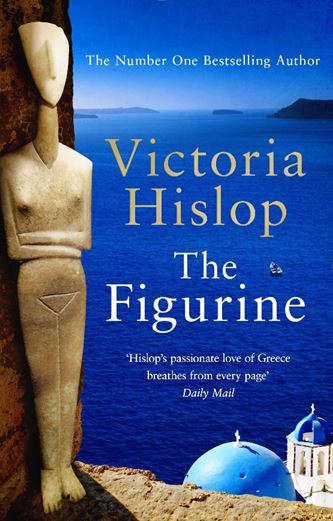

The Figurine is set in Athens, flitting back and forth between the present day and the narrator’s memories of a 1970s childhood under the colonels, and the fictional island of Nisos (“I thought, if I can teach somebody just one word of Greek that way, I would”), where she joins an archaeological dig. On said dig, she begins to wonder about the provenance of the collection of antiquities in her grandfather’s Athenian apartment. Victoria explained how her philhellenism had its origins in Twentieth century Greece, admitting to having had little interest in its ancient archaeology. However, that was before seeing a Cycladic statuette in a museum a decade ago, and it was the ascetic simplicity of the folded-arm figurine that caused a “sudden and unexpected inspiration”.

We were among friends (literally, in the Friends’ Room) at the Hellenic Centre, with the Q&A revealing a healthy mix of literary types and philhellenes in the audience. Nevertheless, it felt positively luxurious to hear Victoria, even with her new book to plug, devote nearly half her allotted 45 minutes to the Parthenon Marbles. Rather than make a precis, I’ll let her speak for herself on navigating the past, the virtues of artistic licence, and Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin.

“This book is a metaphor for removal and exploitation. Stolen things still turn up – and vague provenances conceal a lot. If you’re a purist, where do these things belong?Where something belongs is where it was meant to be, where it was born. InThe Figurine, a Cycladic figurine was taken from a grave. For these characters [the inhabitants of Nisos], it’s not the theft or the current owner that matters, it’s the removal from the grave [that’s the original crime].

“I enjoy writing fictional characters to explore what might happen in the real world. Elgin couldn’t be a character. That’s a line I can’t cross – and I need to like the protagonist! Every now and then[in the book] Elgin does get a mention. A character sees a classical sort-of temple in Edinburgh and feels that’s the wrong environ in which to see that sort of thing. But I don’t want to hit people over the head with[the debate], because I believe it will happen. There’s a wave of worldwide opinion about where artefacts should be. The British[Museum] are like King Canute on the beach. We’re alone in so many attitudes in the UK and this is one of them. It fuel[s] my passion in archaeological theft. Elgin’s removal was theft. The BM is lackadaisical with the facts of the removal. He didn’t intend the sculptures for public consumption, but for his mansion.”

Victoria acknowledged the legacy of non-fiction historical books about cultural trafficking, “the ones that often read like adventure novels”, but also highlighted the humanitarian problems that often accompany theft and trade, not to mention the association with drug trafficking. I was reminded of UNESCO’s Conference on Cultural Traffic held in Olympia in 2014, which I attended alongside former BCRPM Chair Eddie O’Hara. To hear him speak on the Marbles back then, alongside presentations by archaeologists, curators, and diplomats trying to protect the antiquities in their care from upheavals like the Egyptian Revolution of 2011 vividly cast their removal to Britain in a contemporary light.

When, during Victoria’s eloquent synthesis of the problems with the Elgin narrative and the responsibilities of the novelist, David Wills pointed out that writers must often negotiate different versions of the past at once. The author stressed the importance of dealing in facts, “and there are a lot of facts in this case. We can’t carry on being one of the few to ignore the theft, the illegal acquisition, or the bigger story those sculptures can be part of. You get conflicting reports and views[from historical sources], so you read different versions of the same story. Novels allow for bias that you can’t get away with when you’re a historian.”

This can be contrasted with a statement made by Sir Noel Malcolm against Lord Vaizey in last year’s Intelligence Squared debate: that events of the deep past are subject to different judgements and values to those of the present day. Now, we know there’s no changing what’s already occurred. But leaving aside any debate as to whether the early 1800s count as the ‘deep past’, and acknowledging that a fair few BCRPM members are themselves in the business of history, I wonder if a few more people in positions of power could take a pinch of the novelist’s approach, not just to the past, but to the future too: we know that our beloved statues’ continued presence in the British Museum's Room 18 is not a historical inevitability, and that their part in Britain’s story (to borrow the BM’s attitude) so far doesn’t guarantee permanence – they’re part of the once and future legacy of Greece.

Stuart O'Hara, BCRPM member