Law, Morals and the Parthenon Marbles

Treachery, subterfuge and "a steady flow of bribes." Writer Bruce Clark unpicks the dubious legality of Lord Elgin's removal of the Parthenon sculptures.

Does the status of the Parthenon sculptures amount to a simple question of ethics or a complex, but ultimately soluble, question of law? That is one way of describing the difference between those who want to see the treasures reunited in Athens, and those who would leave them in London.

When Melina Mercouri went to London in 1983, she put the point in her own inimitable way: “This is a moral issue more than a legal issue.” Kyriakos Mitsotakis took a similar line in November when he visited his counterpart Boris Johnson and declared that the sculptures were stolen – a view which Johnson himself, in his student days, had espoused.

The British Museum’s position is diametrically opposed. Its website argues that Elgin acted with the full knowledge and permission of the legal authorities of the day in both Athens and London. Lord Elgin’s activities were thoroughly investigated by a Parliamentary Select Committee in 1816 and found to be entirely legal.

Provocative as it sounds to most Greek ears, the case for the legality of the marbles’ transfer is worth studying. It rests mainly on a document that was apparently issued by an Ottoman official, the kaymakam, at the request of the British embassy to the High Porte, around the beginning of July 1801. It emerged at a high point in Anglo-Ottoman relations, when the two powers were acting in lockstep to expel Napoleon’s forces from Egypt. It was not, strictly speaking, a firman – a term which refers to a decree issued by the sultan himself. But the kaymakam was a high-ranking figure.

Its terms had virtually been dictated by Elgin’s assistant, a shrewd Anglican cleric, Philip Hunt. It allowed a team of mainly Italian artists employed by Elgin to visit the Acropolis, which was also the Ottoman garrison, make drawings and moulds of the antiquities, and specified that …“When they wish to take away some pieces of stone with old inscriptions, and figures, no opposition be made…”

Historians agree that when that text was issued it was understood to refer to picking up objects from or below the ground. (Ever since the explosion of 1687, when a Venetian mortar bomb ignited an Ottoman powder-keg and blew the roof off the Parthenon, plenty of valuable debris had been scattered around on the citadel).

In the course of July 1801, Anglo-Ottoman relations became closer still as fears grew that Napoleon might invade Greece. Hunt was sent back to Athens – on a mission to stiffen the backs of the Ottoman commanders. As he boasted afterwards, this provided an opportunity to “stretch” the meaning of the permit and remove sculptures that were still attached to the temples. In the careful words of historian William St Clair, “Lord Elgin’s agents, by a mixture of cajolery, bribes and threats, persuaded and bullied the Ottoman authorities in Athens to exceed the terms” of the kaymakam’s decree.

As Elgin would later explain, such a document was in any case not the last word – it was a basis for negotiation with local officials, and it did not preclude the need to keep up a steady flow of bribes to ensure that the stripping of the Acropolis continued unimpeded.

Conveniently for Elgin, the post of disdar, or head of the Acropolis garrison, changed hands in mid-1801, as an elderly incumbent, who’d made a steady income in bribes, passed away and the job was taken over by his son. The new disdar felt trapped in the middle of a high-stakes transaction, and he feared dire punishment if he miscalculated. Elgin and his associates made sure that he remained frightened. In May 1802, the disdar became anxious that he might get into trouble with his Ottoman masters because he had been slightly too zealous in accommodating Elgin’s project. But as Lady Elgin smugly reported, one of her husband’s agents “whistled in his lug (ear)” that he had nothing to fear. Or to put it another way, “You have nothing to fear but us…”

Even then, the Ottoman attitude to the legality of the project was never a settled matter. In autumn of 1802, both the disdar and the voivode (governor) of Athens became worried that they might get in trouble with the Porte, because the existing text did not justify the mass stripping which was in progress. Elgin duly procured a fresh document which retroactively legalized the actions of the two officials.

But then fast-forward to 1808, by which time the kaleidoscope had shifted: the Ottomans were at peace with France and spasmodically at war with the British. Many of the sculptures collected by Elgin were still in Greece.

A new British envoy to the Porte tried to get the sculptures released, and was bluntly told that Elgin’s entire operation had been illegal. Only after January of 1809, with the signature of a new Anglo-Ottoman treaty, did the atmosphere change, leading to a fresh document that enabled the export of the sculptures to resume.

During the parliamentary investigation which the British Museum mentions, Elgin was questioned hard as to whether he had abused his position as ambassador to pursue a personal transaction; he replied, absurdly, that, in his antiquarian activities, he was no different from any private archaeologist. But many legislators were unconvinced.

It seemed obvious that the objects for which Elgin was about to be paid £35,000 had been obtained by careful exploitation of diplomatic privilege and of the sweet state of Anglo-Ottoman relations. Elgin got his money, but that does not mean he was believed.

Is this really the kind of behaviour on which British officials should be basing their case? By stressing the very dubious argument for the legality of Elgin’s actions, they risk drawing further attention to the fundamental moral issues.

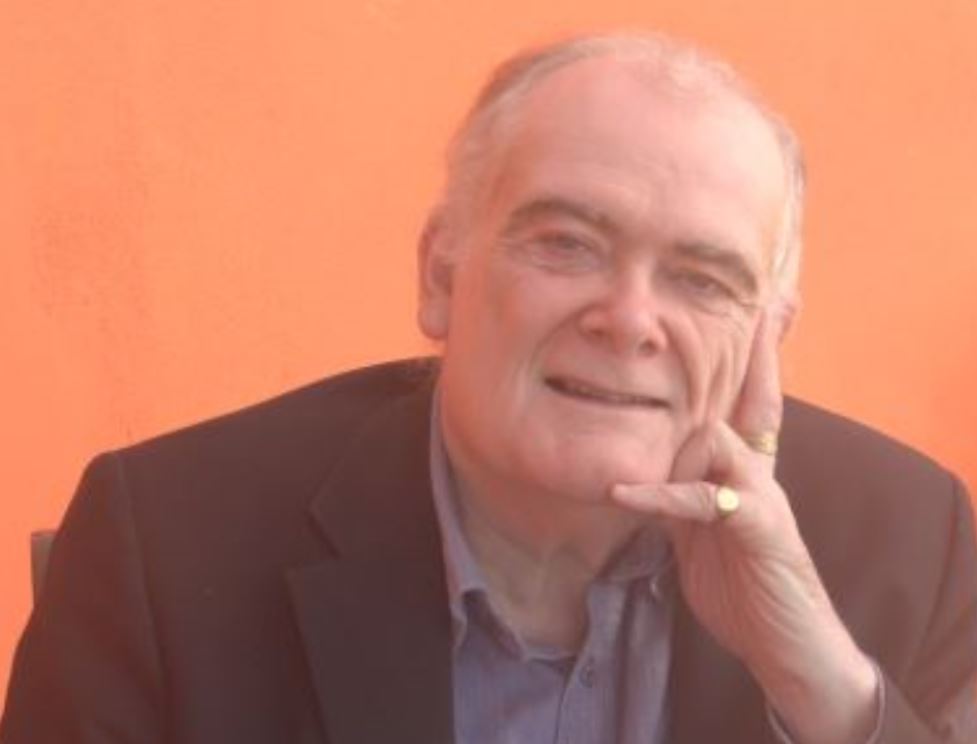

* Bruce Clark writes for The Economist on history, culture and ideas. He is author of his latest book “Athens: City of Wisdom.”

This article was previously published in Greek at kathimerini.gr, 18 February 2022

Bruce Clark also contributed his article 'Stealing Beauty' to BCRPM's articles section of this website.