Ancient gods and centaurs flickered to life, horses, owls and deer danced across the Athenian skyline, and statues of ancient girls blinked and tossed their hair as Greece opened its New Acropolis Museum, pressing its case that artworks from the 5th century B.C. Acropolis should all be housed together.

"If Pericles' Acropolis was a hymn to beauty, harmony and liberty, the Acropolis Museum today is the Ark which brings together all of the ideas that the Parthenon has stood for ever, since antiquity," Greece's Prime Minister Kostas Karamanlis said in a speech. The museum can help bring "the reunification of the Parthenon marbles. Because the Parthenon marbles speak in their entirety. This is the way to show the integrity of everything they stand for."

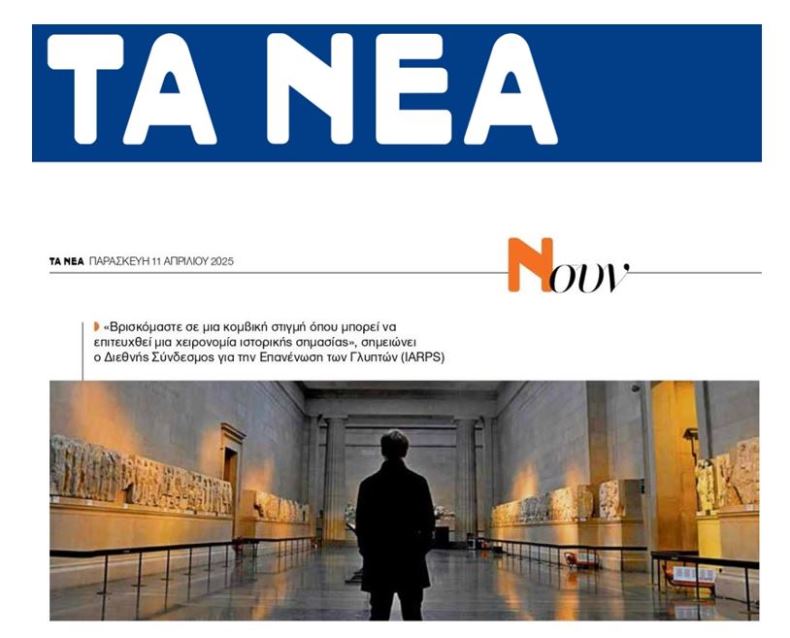

Amid tight security and with a backdrop of animated scenes from the collection in the 130 million-euro ($181 million) museum, Greece is renewing its campaign to retrieve the Elgin Marbles, the sculptures taken from the Parthenon's frieze to Britain 207 hundred years ago and housed in the British Museum. The ceremony was broadcast live on Greek TV and online.

Completed three decades after the first call for a design, and after court cases and archaeological finds delayed construction, the museum is Greece's answer to the British Museum's argument that there's nowhere to house the Marbles.

Gods, Giants

The frieze depicts gods, giants, Greeks and centaurs in the annual Panathenaic procession. White plaster replicas of the stones in the British Museum sit next to the sand-colored stones left behind in Athens in the top glass gallery of the building designed by Bernard Tschumi. A terse "BM" is printed under the items still in London. Museums in Copenhagen and Paris are among others with sections of the stones.

Tschumi's concrete-and-glass structure, with the gallery swiveled to complement the angle of the Parthenon temple on the top of the hill 300 meters above it, houses thousands of works from the Acropolis, some never seen before.

The museum is designed to show the historical and social background of the 5th century B.C., something, Greece contends, lacking in the presentation of the Greek sculptures in the British Museum. The frieze in Athens with its missing pieces is "like looking at a family picture and seeing loved ones who are far away or lost to us," Culture Minister Antonis Samaras told reporters today.

Legal Owner

Successive U.K. governments have said the marbles won't be returned. British Museum director Neil MacGregor, in a 2007 interview, said objects could in theory be loaned for up to six months, though this would be impossible while the Greek government refused to acknowledge the Museum as the legal owner. Samaras said this month that would be unacceptable to any Greek government.

The collection includes artworks such as "the Calfbearer", the oldest statue on the Acropolis, dated to 570 B.C., and the "Cretan Boy", created after 480 B.C., in the Archaic Gallery, which allows visitors to walk around the artworks. The artworks are placed to demonstrate the passage of time and impact of social and political events and how artists started to move away from the stylized forms of the "korres" statues to a more natural appearance.

The Caryatids, the columns sculpted in the form of females, stand in their original formation with a space for a missing member, housed in London. Even during antiquity the details of the backs of the statues weren't visible, Alcestis Choremis, the retired director of Acropolis antiquities said.

Comments powered by CComment