Published: February 2 2008 02:00 | Last updated: February 2 2008 02:00

"It makes sense," says Stelios Haji-Ioannou, purveyor of all things easy and orange, and showing a fine predisposition for Socratic irony, "for easyCruise to be associated with an academic debate of the highest standard." So the travel company, which specialises in inexpensive tourism, is sponsoring a Cambridge Union debate on the return of the Parthenon marbles to Greece. But does it make sense? Really?

I suspect I am not alone in identifying easyJet and its various offshoots with experiences that are less than exalted. Easy on the pocket, yes. But rarely comfortable and frequently vexing. That's fine. I have nothing against cheap and cheerful, still less against the notion of an affordable cruise that encompasses the best of classical Greece - Mycenae, Delphi, Olympia, unmissable treats, all of them.

But where is the synergy between brand and subject? There is the obvious one, of course. While you sun yourself under the Aegean skies, let your thoughts stray on to this most controversial of subjects. Tan while you stew. But on a deeper level, there is no relation whatsoever between the cheap holiday package and this stormiest of intellectual topics; no real affinity between easyCruise and difficultDebate.

Cultural tourism is close to being an oxymoronic phrase. It is just about possible to engage seriously with a cultural artefact while on holiday, although wild horses wouldn't drag me into Florence's hapless Uffizi galleries on a sultry August afternoon. But the cruise is the ultimate let-off for those who prefer their culture lightly spread. There is the twin guarantee of minimal engagement and the earliest possible return to home comfort. (Reader, I don't speak from prejudice. Yes, I have been on a cruise. There was no moment more exciting, nor more keenly felt, during our two-week zip around the treasures of the Mediterranean, than the nightly quiz. Apart, perhaps, from the duty free stop in Gibraltar.)

So the idea that easy access to culture will magically enable us to appreciate its more subtle nuances is a little fanciful. It is a corporate conceit, manufactured by those who have a vested interest in simplifying our lives, when what we really need is a more sophisticated embracing of complexity - which is, after all, what culture is for.

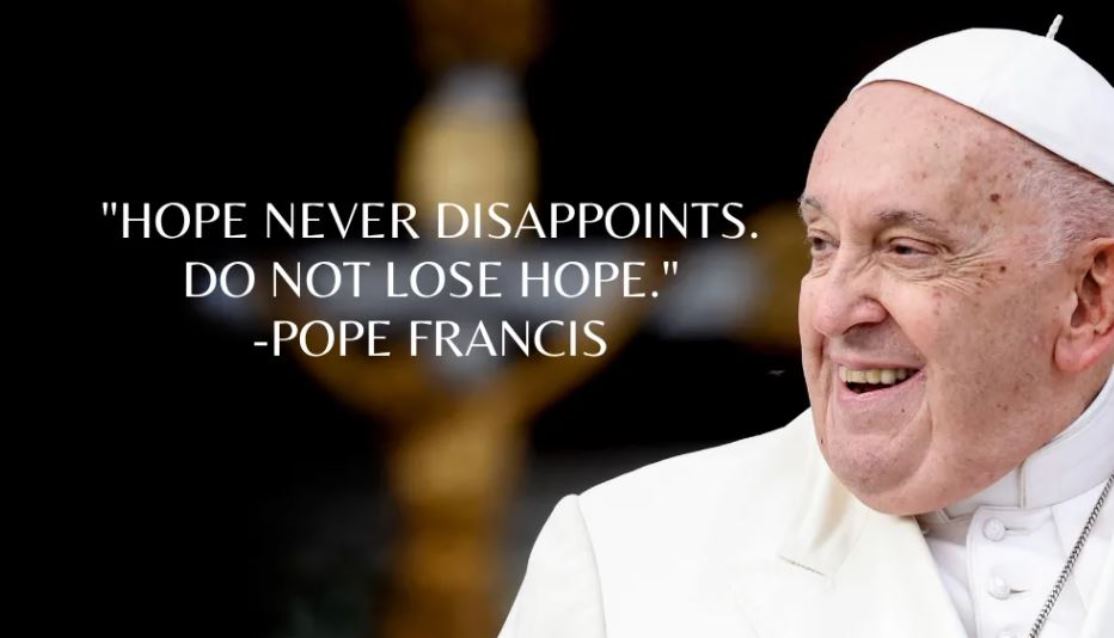

Complex is certainly a word that applies to the debate over the Parthenon marbles. It is a discussion that has evolved organically over the past few decades, comprising some fascinating, and not unhumorous, phases. The Greeks first showed serious signs of wanting their marbles back in the 1980s, in a campaign led by their feisty minister of culture, the actress Melina Mercouri. She had made her name internationally in the splendid 1960s film Never on Sunday , by playing a whore who comes under the wing of a Greek-American classicist ("Homer Thrace") who tries to educate her away from fleshy hedonism and into his joyless library of good intentions.

He fails, of course, and Mercouri took some of her character's headstrong resistance to fusty scholarship into her campaign, appealing unashamedly to the marbles' sentimental significance to the Greek people. She requested an official visit to see the marbles at the British Museum; its then director, Sir David Wilson, fustier than fungus, replied that it was unusual to allow burglars to "case the joint" in advance of their theft. Mercouri went on to charge Sir David with cultural imperialism; her antagonist, warming to the hostilities, accused her of "cultural fascism - like burning books, that's what Hitler did".

So far, so stroppy. There will be similar fusillades, you can be sure, at the Cambridge Union this month. But the Greek position changed dramatically at the beginning of the millennium, as a newly pragmatic campaign dropped its insistence on legal ownership of the marbles, and concentrated instead on bringing the various pieces together under one roof (they are currently split, roughly equally, between the two countries.) Only it was never going to be a roof in Bloomsbury, London. A new Acropolis museum was built to receive the returning treasures. If they did not return, the museum would remain partly, and pointedly, empty.

And this is where the story gets infernally, thrillingly, complex. The British Museum's new director Neil MacGregor wisely disdained Sir David's de haut en bas sarcasm. Museums are for telling stories, he said. In Athens, the marbles tell the story of the birth of democracy in its very birthplace; in London, they are part of the wider story of the European Enlightenment. Both stories are equally important; both stories are being served in the two great capital cities. What could be fairer?

And this is where the debate remains today. Somewhere between heart and mind, emotion and reason. The heart feels sorry for the empty corridors of Bernard Tschumi's deftly conceived new museum; the mind understands, with MacGregor, the postmodern moment in which we find ourselves, having to deal with a multiplicity of narratives, and wrestling with the need to treat them all justly and sympathetically.

I feel the dilemma more acutely than most. Half-English, half-Greek, I have been moved, educated, enlightened and enraptured both in the side streets that snake around the Acropolis and in the stately rooms of the British Museum, which speaks of world culture as no other place. What upsets me most is the trivialisation of this debate, the biff-bang polemics that will doubtless resound around the Cambridge Union, that depressing training ground for shrillness and superficiality. This issue matters. But the answer? It's anything but easy.

More columns at www.ft.com/aspden

Comments powered by CComment