THE NEW ACROPOLIS MUSEUM

published: TIME October 28, 2007

I got a preview a few days ago of the new Acropolis Museum in Athens. Any building has to accomodate its site, and for some the site can be a very delicate matter. (You've heard of the World Trade Center, no?) But I can't think of another building where the site has dictated the design as much as this one, and where the building has responded so adroitly. Then again, it's hard to think of a site that compares to this one in importance.

Actually, the Swiss-born, New York and Paris-based architect Bernard Tschumi had to answer to two demanding sites. One is the ground his museum actually rests on. Tschumi's angular design spearheads its way into a dense quarter of town at the foot of the Acropolis, a plot of land that also was also a sensitive archeological dig. No surprise, stick a spoon into the ground anywhere in Athens and you have one of those.

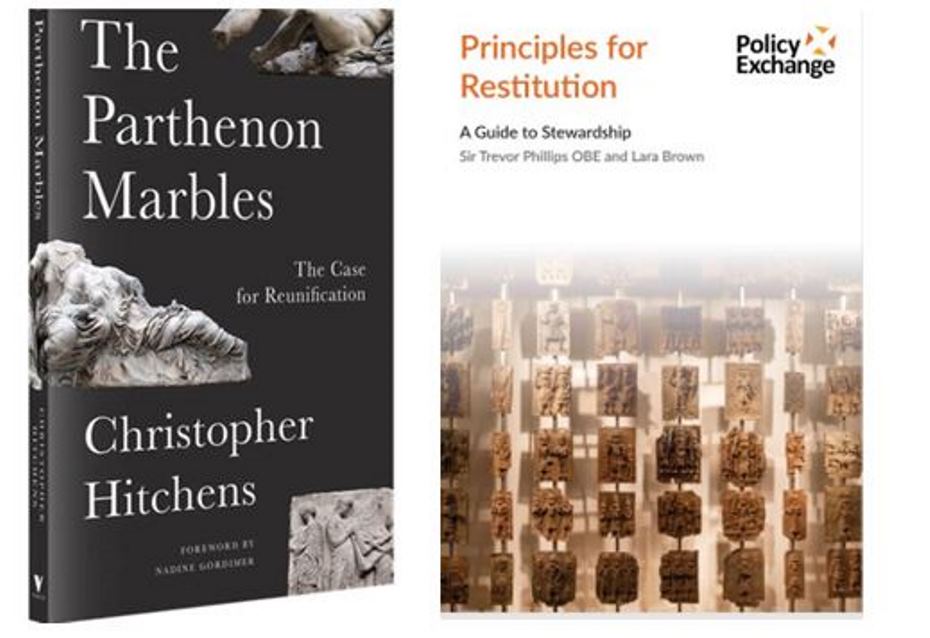

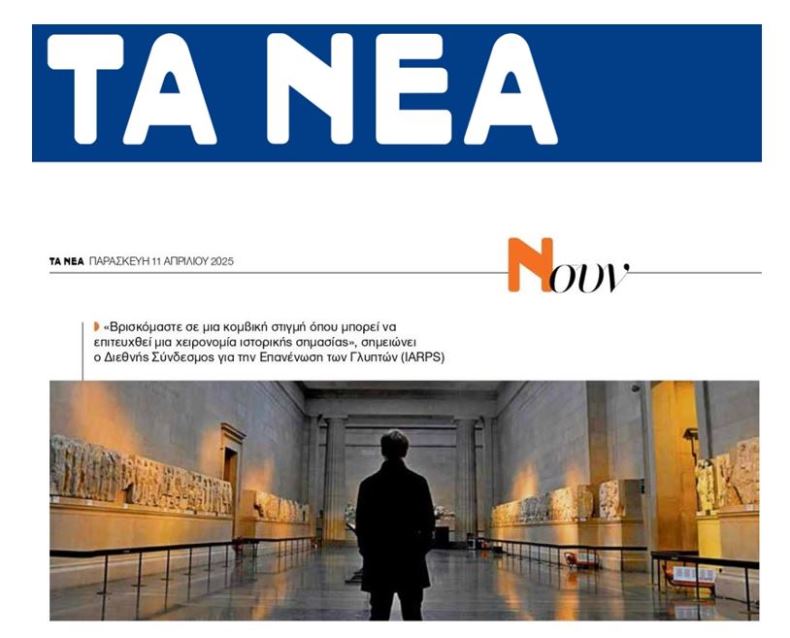

The other site is the one his building addresses — the Parthenon itself, about 150 ft. above the museum and 1000 ft. to the north. Tschumi's museum is a kind of polemic in glass and concrete, conceived as an argument by the Greek government to bid for the return of the Elgin marbles, the Parthenon carvings carted off to London two centuries ago by Lord Elgin and now in the possession of the British Museum.New Acropolis Museum/Bernard Tschumi -- Images: Courtesy New Acropolis Museum.

The Greeks still possess 36 of the 115 panels in the Parthenon frieze. A single long depiction of what's presumed by most scholars to be the Panathenaic procession, it once ran around the perimeter of the inner walls. They also have 39 of the 92 metopes, separate blocks that ran above the exterior colonnade and showed scenes from Greek legend. To display all this as powerfully as possible, Tschumi has provided a multi level structure around a concrete core that has the same dimensions as the perimeter of the Parthenon. The Greeks still possess 36 of the 115 panels in the Parthenon frieze. A single long depiction of what's presumed by most scholars to be the Panathenaic procession, it once ran around the perimeter of the inner walls. They also have 39 of the 92 metopes, separate blocks that ran above the exterior colonnade and showed scenes from Greek legend. To display all this as powerfully as possible, Tschumi has provided a multi level structure around a concrete core that has the same dimensions as the perimeter of the Parthenon.

You might say that the first level is the dig itself and the subterranean remains of an ancient town it uncovered. Into that delicate cavity Tschumi has gingerly introduced large concrete pilings, structural supports that allow the museum's entry plaza and first floor to hover over the site without dislodging too much of the findings below. Wide expanses of glass cut into the floor at several places allow visitors to look down into the ruins as they move into the museum.

The palette everywhere is steel and concrete gray, with mostly bare walls and blunt columns — Modernism speaking to its Classical roots at their most austere, but without simply reproducing the rectangulars of a temple. In fact the next two levels have trapezoidal floors for the lobby, shop and restaurant and for galleries that will hold artifacts from the Mycenean period to the early fifth century B.C., just before the Parthenon was begun.

What all of this amounts to of course is a complicated processional space that prepares you for the uppermost gallery, glass walled on all four sides, that will hold the frieze tablets and metopes. As I realized when I visited the Parthenon later the same day and again the next, your initial movements through the museum will subtly recall the walk up the Acropolis slope to the Parthenon at the top, one that nearly all visitors to the museum will also have made.

On the northern side of the glass walled galleries you can look up to the Parthenon and see the southern face from which Elgin stripped nearly all of the metopes that he managed to get. On the wall behind you, the remaining frieze panels and metopes will be organized in long lines that reproduce their original positions on the temple. The marbles that are in London will be represented in the appropriate positions along side them by copies covered with a fine mesh. These will be placed beside the marbles that the Greeks still possess, both to sustain the narrative continuity of the frieze, and of course, to serve as constant reminders of what's missing. It's here that Tschumi mustered his simplest means into his most well considered and powerful effect. The museum as optical device, the optical device as polemic.

Back outside, Tschumi's museum is also satisfying in the way of certain startlingly modern buildings inserted into old European city fabrics. Standing on the plaza outside the main entrance you see ancient Athens below you in those exposed ruins, the 19th and 20th century city around you and a 21st century building rising above you. If you know the elegant modernist box that Richard Meier designed to surround the Ara Pacis Altar in Rome, a treasure from the 1st century B.C., you know what I mean.

Until now the Parthenon marbles still in Greece were displayed in the old museum on the Acropolis. A few weeks ago workers began transferring them in crates by way of huge cranes to the new museum. Some of those crates are already on the upper gallery floor, but the marbles won't be fully installed for months. Early next year, while installation is still underway, the public will be admitted into the new museum, with an official opening set for some time in early 2009. Athens hasn't seen a thunderbolt like this since Athena last threw one. Will it carry out its assigned task, to summon the Elgins back? For once the cliche works so well it really can't be avoided. If you build it, will they come?

Comments powered by CComment