October 28, 2007

Where Gods Yearn for Long-Lost Treasures

By NICOLAI OUROUSSOFF

for the New York Times

NO sane architect, one can assume, would want to invite comparisons between his building and theParthenon. So it comes as little surprise that the New Acropolis Museum, which stands at the foot of one of the great achievements of human history, is a quiet work, especially by the standards of its flamboyant Swissborn architect, Bernard Tschumi.

But in mastering his ego, Mr. Tschumi pulled off an impressive accomplishment: a building that is both an enlightening meditation on the Parthenon and a mesmerizing work in its own right. I can't remember seeing a design that is so eloquent about another work of architecture.

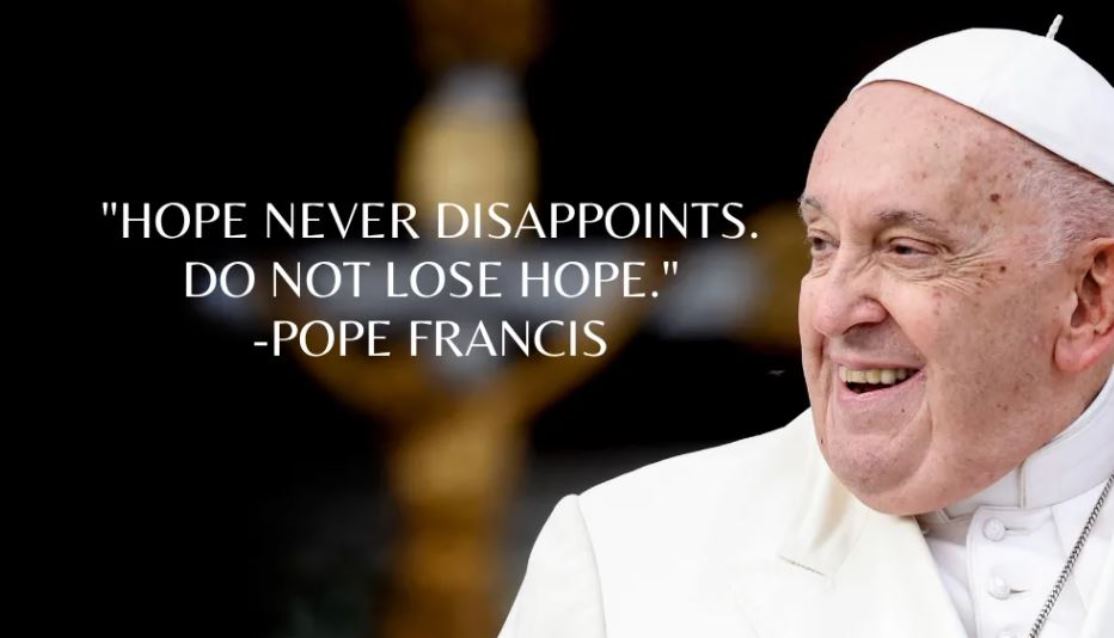

When this museum in Athens opens next year, hundreds of marble sculptures from the old Acropolis museum alongside the Parthenon will finally reside in a place that can properly care for them. Missing, however, will be more than half of the surviving Parthenon sculptures, the Elgin Marbles, so called since they were carted off to London by Lord Elgin in the early 19th century.

Britain's government maintains that they legally belong to the British Museum and insists that they will never be returned. The Greeks naturally argue that they belong in Athens.

Until now my sympathies tended to lie with the British. Most of the world's great museum collections have some kind of dubious deals in their pasts. Why bother untangling thousands of years of imperialist history? Wise men avert their eyes and move on.

But by fusing sculpture, architecture and the ancient landscape into a forceful visual narrative, the New Acropolis Museum delivers a revelation that trumps the tired arguments and incessant flag waving by both sides. It's impossible to stand in the top-floor galleries, in full view of the Parthenon's ravaged, sun-bleached frame, without craving the marbles' return.

The museum's rhetorical power may surprise people who have followed the project over the last six years. Mr. Tschumi won the competition with a design that seemed chaste and austere by comparison with the flamboyant confabulations that are now common in contemporary museum design.

The museum had to respond to more than 100 lawsuits before construction could begin, including disputes over its location and whether the sculptures could be moved without putting them at risk. (Local preservationists are now fighting to block plans to demolish two landmark buildings — an Art Deco gem and a lesser neo-Classical structure — that block the sightlines from the museum to an ancient amphitheater at the base of the Acropolis.)

But the end result is a remarkably taut and subtle building. When I first glimpsed it on the approach from Dionysiou Areopagitou Street, a pedestrian avenue that leads from the Plaka cafe district, it seemed to fade into the dense grid of the city. Its facade, heavy bands of glass atop a concrete base punctured by narrow windows, seemed calm and unobtrusive.

Yet as I drew closer, the forms grew more precarious. To preserve the ruins of an ancient village that was discovered at the site during construction, the entire building has been raised on huge columns. A wildly overscale concrete canopy juts over the main entry plaza. Just above, the museum's top floor seems to shift slightly, its corners cantilevering over the edge of the story below as if it is sliding off the top of the building.

This instability sets in motion a carefully paced narrative, guiding you through centuries of Greek history and allowing you to see the Parthenon with fresh eyes. An elliptical cutout in the plaza floor offers a view of the archaeological ruins below. From there you head into a low, dusky lobby and turn onto a vast ramp that leads to the main galleries.

Sunlight spills down through a concrete-and-glass grid several stories above; the floor of the ramp is a grid with fritted glass panels that allow additional glimpses of the subterranean ruins. As you walk upward, you pass a series of chiseled figures on gray marble pedestals before arriving at an Archaic limestone pediment at the top of the ramp.

The procession echoes the climb to the Parthenon, which culminates when you pause before the stark columns of the Propylaea, or entrance. Yet only as you turn the corner and enter the main gallery do you begin to grasp the significance of the journey. This vast space, now empty, will soon be filled with sculptures of gods and other mythological figures dating from the Mycenaean period to the early fifth century B.C. A fragment of a marble pediment that depicts Athena wrestling with giants — an example of the unrestrained, expressive style that preceded the controlled vigor of the High Classical period — will anchor the gallery's far end. From there you loop around to more escalators and stairs, leading to a mezzanine restaurant and a small gallery that will house a balustrade from the Temple of Athens depicting the goddess flanked by winged Nikes.

The sequence brings to mind a 1940 essay by the Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein in which he described the Acropolis as one of the world's most ancient films because of the way you experience it as you move through space. "It is hard to imagine a montage sequence for an architectural ensemble more subtly composed, shot by shot, than the one that our legs create by walking among the buildings," he mused.

Like Eisenstein, Mr. Tschumi aims to create a montage of visual experiences. The roaming viewer stands in for the camera, collecting and reassembling these images along the way. Only when you reach your destination do they fuse into a coherent vision.

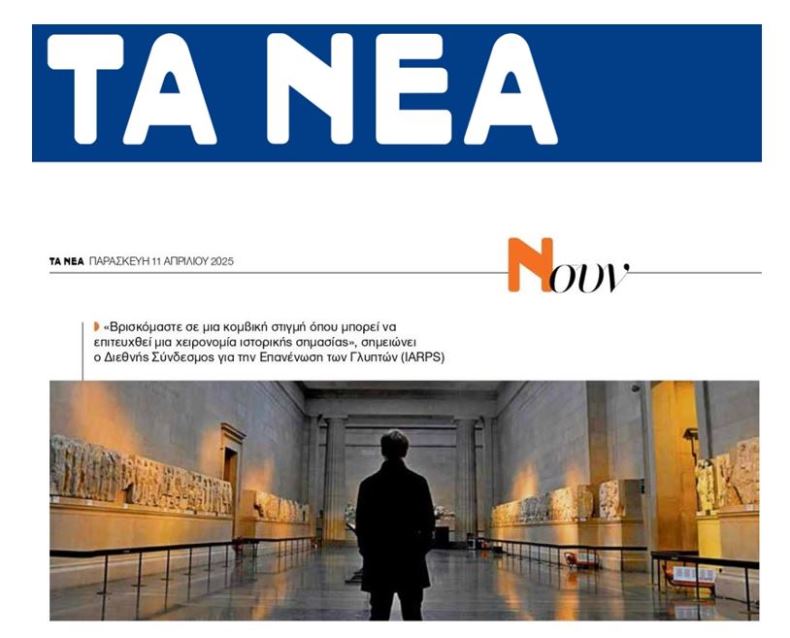

The sense of anticipation reaches its full pitch as you enter the museum's top-floor galleries. They echo the layout of the Parthenon itself, with a colonnade set around a sacred inner temple chamber. The temple friezes will be mounted in an unbroken sequence along a central core so that you will be able to follow the narrative without interruption. The panels lost to antiquity will be left blank; those that remain in the British Museum will be reproduced in plaster yet covered by a diaphanous veil to make clear that they're fakes. The entire floor is wrapped in glass so that you can gaze at the surrounding city.

The genius lies in how the room snaps disparate sculptural and architectural fragments into their proper context. You first enter the south side of the gallery, where the museum's friezes and metopes will be seen against the chalky backdrop of the rooftops of Athens. As you turn a corner, the Parthenon comes into full view; the ancient temple hovers through huge windows to your right. The eastern facade of the Parthenon and the sculptures that once adorned it unite in your imagination, allowing you to picture the temple as it was in Periclean Athens. Eventually you descend through a sequence of smaller galleries, where the glories of the High Classical period gradually give way to Roman copies of Greek antiquities. The Parthenon fades from view.

It's a magical experience. Rather than replicating or simply echoing the Classical past, Mr. Tschumi engages in a dialogue that reaches across centuries.

I carried these thoughts with me as I boarded an evening flight to London shortly after touring the museum. The next morning I walked from my hotel to the British Museum to visit the Elgin Marbles. Inside the long, narrow Duveen Gallery I felt an immediate twinge of pain. The marbles were stunning, but they looked homesick.

To give visitors some sense of where they were in the Parthenon, the curators have hung the friezes along two facing walls, with the pediments set at each end of the gallery. Even so, you read them as individual works of art, not as part of a composition.

A panel depicting the receding tail of one horse and the advancing head of another with an expanse of blank stone in between is breathtaking. But it's hard to picture how it originally fit into the Parthenon. The lack of context is only reinforced by Lord Elgin's decision two centuries ago to cut the works out of the huge blocks of stone into which they were originally carved, a cruel act of vandalism intended to make them easier to ship.

In dismantling the ruins of one of the glories of Western civilization, Lord Elgin robbed them of their meaning. The profound connection of the marbles to the civilization that produced them is lost.

Mr. Tschumi's great accomplishment is to express this truth in architectural form. Without pomp or histrionics, his building makes the argument for the marbles' return.

Comments powered by CComment