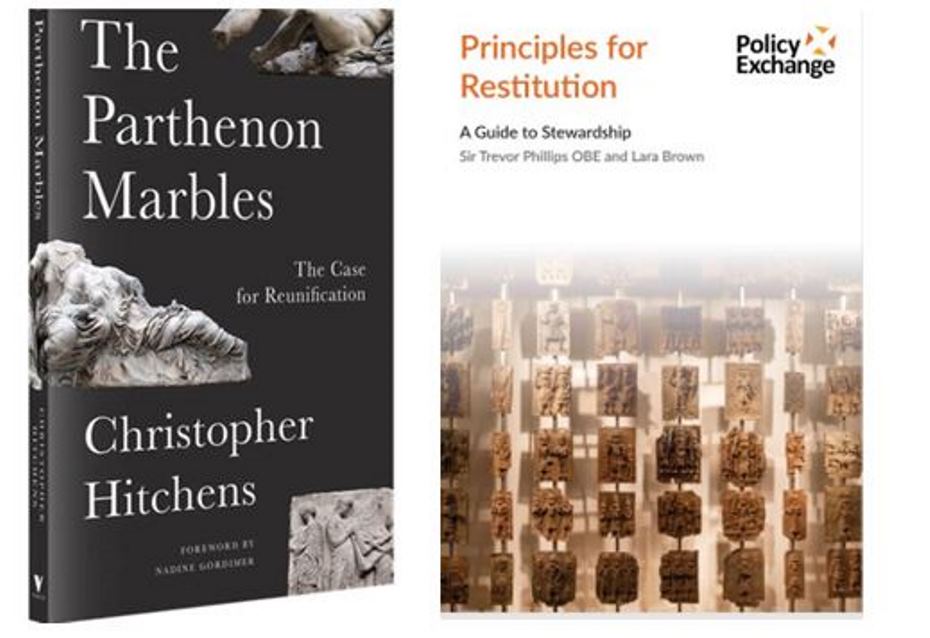

When the Parthenon Sculptures came to London it was the first time that they could be seen at eye-level. They stopped being architectural details in the Parthenon and became sculptures in their own right. They became part of a different story — of what the human body has meant in world culture. In Athens they would be part of an exclusively Athenian story.

Neil MacGregor, Directorof the British Museum

Neil MacGregor: ‘There is no possibility of putting the Elgin Marbles back’

The British Museum director explains why the Parthenon Sculptures will not be returned to Greece during his tenure.

During his 15 years in charge of the National Gallery, Neil MacGregor was nicknamed Saint Neil by his adoring staff, partly because of his Christian beliefs and partly because he ran that place with a heavenly touch. After 12 years at the helm of the BM the halo is still in place — just.

It’s hard to recall now how disunited and financially adrift the mighty Bloomsbury institution seemed before MacGregor arrived. He has pulled it round and his own adroit media achievements — notably the marvellous BBC Radio 4 series 'A History of the World in 100 Objects'— have given its treasures a much higher profile. With a new book and another Radio 4 series, he is doing the same thing for the BM’s latest big exhibition:'Germany, Memories of a Nation'.

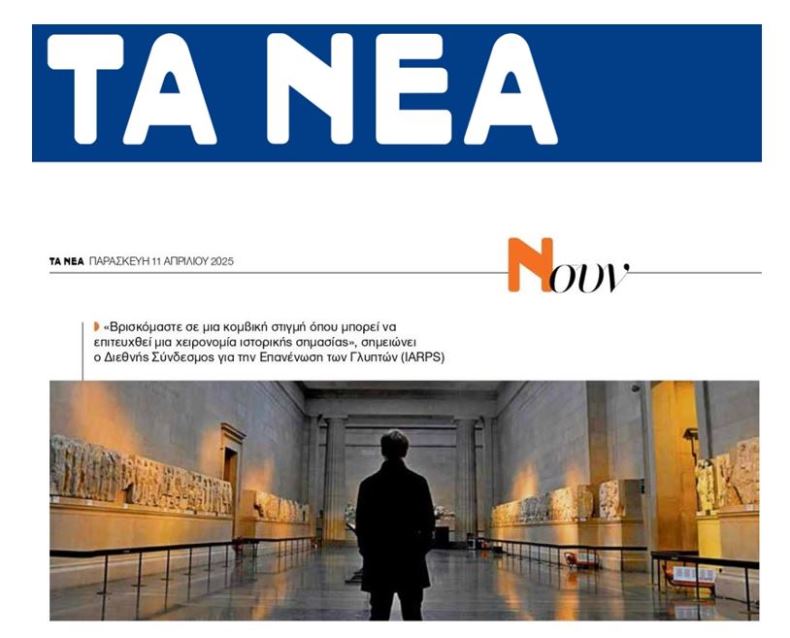

Yet in some quarters, particularly around southern Europe, MacGregor is regarded more as devil than saint. He has never wavered from his view that the Elgin Marbles (or the Parthenon Sculptures, as the BM officially calls them) should stay in Bloomsbury rather than be returned to Athens, from where they were removed by Lord Elgin between 1801 and 1805. Now the Greeks are mounting their strongest attack on the BM’s position since the 1970s heyday of Melina Mercouri. They have hired a team of media-savvy human rights lawyers, including Geoffrey Robertson and Amal Clooney (wife of George). With a film about wartime art looting to publicise, Clooney himself also joined the attack earlier this year. Unesco, no less, has now called on Britain to take part in a “mediation procedure” with the Greeks to resolve the issue.

Saintly or not, MacGregor visibly bristles at that suggestion. “UNESCO is an intergovernmental organisation but the trustees of the British Museum are not part of the British government,” he says. “The British government does not own the great cultural collections of this country. The pictures in the National Gallery, the objects in the British Museum, are held by the trustees and their duty is to preserve the objects for the study and enjoyment of the whole world. They have a charitable responsibility imposed by law to ensure that those objects give maximum public benefit.”

It’s the belief of MacGregor and his trustees (who, he points out, include “two Nobel prize-winners and distinguished people from all over the world”) that the Marbles will give “maximum public benefit” by staying in London, rather than going to a new museum in Athens. “From its beginning 250 years ago, the point of the BM was gathering together objects in one place to tell narratives about the world,” he says. “When the Parthenon Sculptures came to London it was the first time that they could be seen at eye-level. They stopped being architectural details in the Parthenon and became sculptures in their own right. They became part of a different story — of what the human body has meant in world culture. In Athens they would be part of an exclusively Athenian story.”

Athenian? “Yes. It’s not even a Greek monument. Many other Greek cities and islands protested bitterly about the money taken from them to build this in Athens.”

Surely one of the strongest Greek arguments is that all the Parthenon Sculptures should be reunited — and the obvious place for that to happen is as close to the Parthenon as possible. “Well, about 30 per cent of the Sculptures are in Athens and 30 per cent are here,” MacGregor counters. “You don’t have to be very mathematical to see that quite a lot of them no longer exist. So there’s no possibility of recovering an artistic entity and even less of putting them back in the ruined building from which they came. Indeed, the Greek authorities have continued Lord Elgin’s work of removing sculptures for exactly the same reason: to protect them and to study them.”

Another argument put forward by the Greeks is that the Marbles were illegally removed by Elgin. He certainly negotiated with the ruling authorities in Athens, but in the early 19th century that was the Ottoman empire, not the Greeks. “Was the acquisition legal?” MacGregor asks rhetorically before answering himself with a rather optimistic generalisation: “I think everybody would have to agree that it was.”

Isn’t the vital document giving Elgin the right to remove the Marbles missing? “You had to surrender the document as you exported,” MacGregor replies — now every inch the tenacious Scottish lawyer he once trained to be. “That’s the point. Everything was done very publicly, very slowly. In 1800 you couldn’t move great slabs of marble quickly. At any point the Ottoman authorities could have stopped it.”

Nevertheless, if artefacts acquired the same way as Elgin acquired the Marbles were offered to the BM today, wouldn’t modern ethical guidelines prevent their acceptance? MacGregor refutes even this, pointing to what he considers to be a present-day parallel. “The BM excavates in Sudan today at the invitation of the authorities,” he says. “And the Sudanese authorities allow us to keep some of what we find.”

So for all Mrs Clooney’s glamorous entreaties, is the BM still determined not even to talk to the Greeks about the future of the Marbles? “On the contrary,” MacGregor says. “The trustees have always been ready for any discussions. The complication is that the Greek government will not recognise the trustees as the legal owners, so conversations are difficult.”

Then how about lending the Marbles (or the parts fit enough to travel) as a temporary exhibition? After all, the BM is (as MacGregor points out) the most generous lender of all the world’s great museums. “The Greek authorities are not interested in borrowing them,” he replies. “That’s sad because these sculptures do belong to everyone. Letting them be seen in different places is important.”

Although the Elgin Marbles row may make him seem like one, MacGregor is far from being a conventional member of the British establishment. He accepted his appointment to the Order of Merit in 2010 but declined a knighthood in 1999 — the first National Gallery director to do so. When I ask him why, he clams up. “We have a convention in this country that we don’t discuss these things,” he says.

He is no more forthcoming about how much longer he might run the BM. “That’s for the trustees to decide,” he says. “I will say that this is a wonderful place to work: living daily with the greatest objects in the world and looking at them with the world’s greatest scholars.” From the fierce glint in his eye I surmise that he’s not going to quit just yet. And while he stays, so do the Marbles.

And our response to the Times

The one entity to which the Parthenon marbles indisputably and inalienably belong is the Parthenon, arguably the most significant of UNESCO World Heritage Sites. They can never cease to be integral elements of its architecture. Together they are one artistic entity, albeit no longer entire but still exceptionally so after 2,500 years. Such a separation of such an important monument is surely unparalleled. They can no longer be displayed in the open air, anywhere, but in Athens alone you have the nearest possible alternative. In the Acropolis Museum they can be viewed in direct line of sight with the Parthenon which can itself be part of the same visit. The case for their reunification is unique and overwhelming.

Eddie O'Hara

Chairman, the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles

Other related articles:

The art world’s shame: why Britain must give its colonial booty back

Debate rages about rights of museums to resist claims on artefacts made by the countries of origin