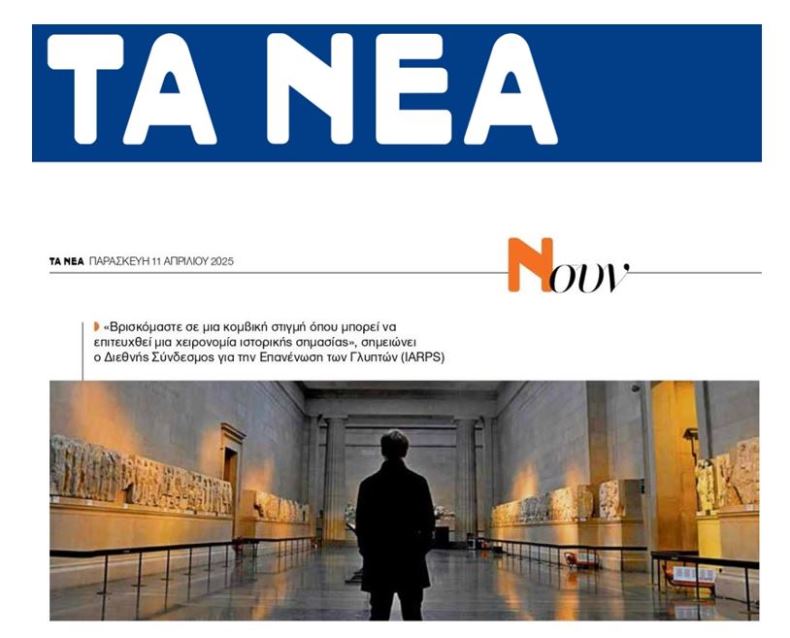

According to the British Committee, the sculptures from the Parthenon deserve to be seen in the Attica light, reports Athanasios Gavos

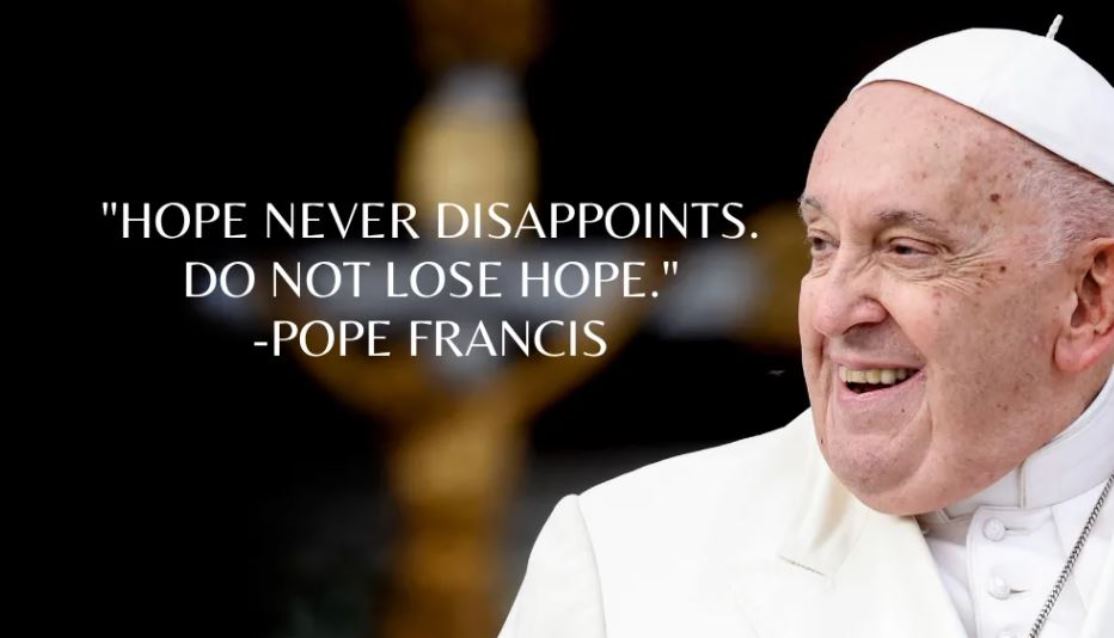

Keeping the issue of the reunification of the Parthenon marbles on the agenda of public debate in Britain is no simple task. This difficult task has been kept alive successfully for 33 years by the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon marbles. Dame Janet Suzman, the BCRPM's Chairperson notes that the sculptures are yearning for the Attica light.

Since its formation, BCRPM has welcomed British members from the fields of literature, art and politics. "We are a particular and enlightened project. We participate in literary festivals, organize special events and opinion polls, but we also support international initiatives formally and informally. Above all, we support the efforts of the Greek authorities, both of the Government and academic institutions", explains Vice-Chairman Professor Paul Cartledge.

"The British Museum could become a truly moral, world Museum of the 21st century, recognizing that Athens, having built a home for the Parthenon sculptures, is worthy of exhibiting the surviving fragmented pieces in the Acropolis Museum" comments Dame Janet Suzman. She strongly feels the sculptures should be seen in the context for which they were intended, namely as the pinnacle of glory of the Parthenon, which still stands, just a glance away from the windows of the Parthenon Gallery in the new Museum.

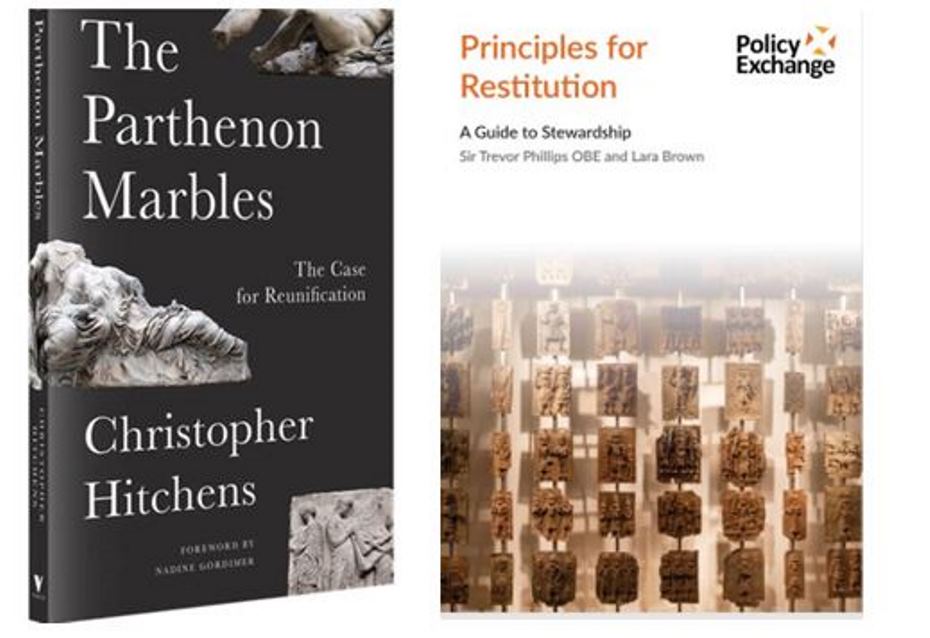

The debate of the sculptures and the option to pursue a legal route for their return to Athens recently returned to prominence after the proposal made by well-known lawyer Geoffrey Robertson for the request to be made prior to the Brexit negotiations for a possible exchange of concessions between Britain and Europe.

"We see no value in unilateral demands such as those proposed by Mr. Robertson," answered the Vice-Chairman of the Committee Paul Cartledge. "This legalistic approach to the reunification of the marbles was looked into by the Greek Government and was rejected."

Dame Suzman adds that the presence of sculptures in London sends the wrong message. "What lessons are we giving to young people visiting the British Museum on a school trip? That it is OK to take something that doesn't belong to you? It's OK to cause damage to the sculpture and building they belonged to and then go on to keep them for over 200 years as an inspiration for Western art and that this can only be done in the British Museum?"

"Modern Athens also has millions of visitors from around the world and these incomparably pieces seek to exposed with views to the Parthenon, beneath the blue attic sky and not in a gloomy gallery of Bloomsbury", concludes Dame Suzman.

However, there is always optimism. In response to the question what would the reunification of the marbles in Athens mean, Professor Cartledge effortlessly replies with one word "Bliss!" And "for the Greeks it would correct a 200 year old error, and for mankind the chance to finally see all the surviving Parthenon marbles together in a specially built Acropolis Museum - in view of the building they once belonged to, the Parthenon."

"For the rest of the world and especially for visitors to the British Museum, there would be the opportunity to see ancient Greek artefacts that have not travelled outside of their country of origin. For academics this would be the opportunity to study all of the remaining original sculptures in a single space."

Dame Janet Suzman stresses the moral issue, which lies at the core of the Greek argument's favour of the reunification of the Marbles: "an adopted child is allowed by law to search for its biological parents once it becomes of age. Surely 200 years of separation is long enough for these 'adopted objects' to at last be reunited with the rest of their family."

19 April 2017

The original article can be viewed here. We apologise for any misinterpretations to the translation of the original article, which is written in Greek.