‘Scaped from the ravage of the Turk and Goth,

Thy country sends a spoiler worse than both’

In 1809, the young Lord Byron, one of the prominent figures of the Romantic Movement and the most liberal voice of the time, during his first trip to Greece, visited the Parthenon. The mutilation of the monument by Lord Elgin was still fresh and the magnitude of the crime shocked the young philhellene. In the poem-complaint "The Curse of Minerva", which he wrote in Athens on March 17, 1811, he asks the goddess Athena (Minerva) to punish the perpetrator, who took advantage of his position against an enslaved people.

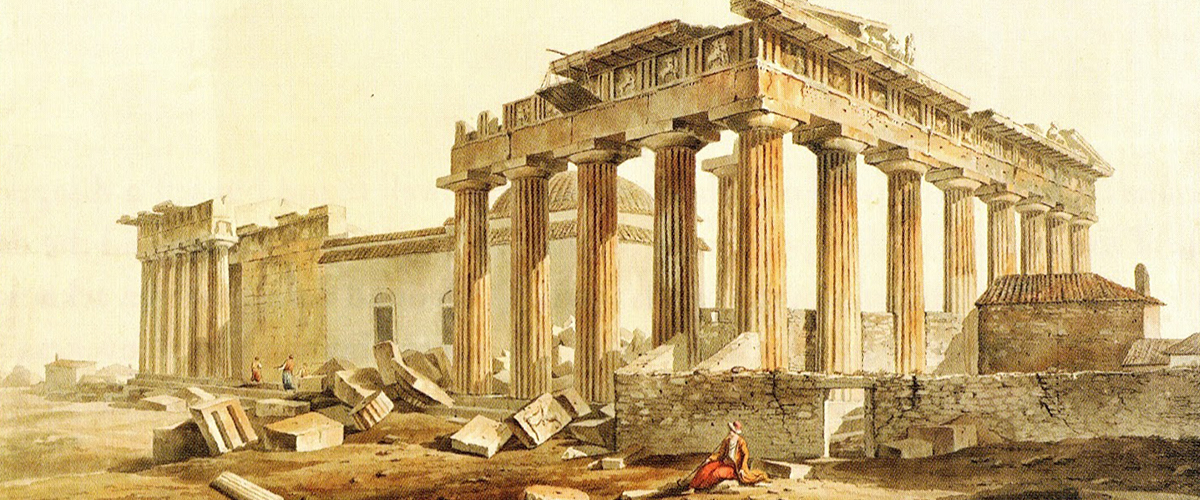

The vandalized Temple of the Athena Parthenos was rendered by foreign traveler painters, such as the Irish painter and antiquarian E. Dodwell, sparking an international outcry, along with the "Curse of Minerva" and the " Childe Harold's Pilgrimage " written by Lord Byron a year later.

On March 10, 1812, John Murrey, publisher and friend of Byron, published Childe Harold's Pilgrimage. In this long poem, the hero wanders in countries and places, records his impressions, making bitter thoughts about the looting of monuments by Elgin. Five hundred copies, priced at 30 shillings each, sold out in three days. Over the next two days, another 3,000 copies of a 12-pound version was released, causing Byron to exclaim, "I awoke one morning and found myself famous!"

The enormous success of Childe Harold's Songs, and its translations into European languages, meant that Byron's thoughts and references to Greece were read by more readers than all travel books combined.

From 1812 onwards, Greece entered the consciousness of Western Europeans and Americans as a place inhabited by modern people, whose political future began to be recognized as a problem that should be addressed, contributing to the strengthening of philhellenism.

Ironically, the depredations to the Acropolis of Athens by Elgin and the acquisition, in 1817, of the "Elgin Marbles" by the British Museum were a decisive factor in Britain in the ascendancy of classical Greece. (St Clair 1998; King 2006). In Germany, the process had begun earlier, around 1750, through the writings of the scholar art historian Johann Winckelmann, father of classical archeology and founder of the movement of neoclassicism.

The condemnation of Elgin's activities in his country by prominent personalities contributed to the Parthenon Sculptures being evidence of the living conscience of the Greeks, who, as descendants of the Ancients, acted as custodians of their ancestral heritage.

The presence of the Sculptures in London and the discussion they provoked significantly influenced the aesthetic perception in British society and beyond. At a time when classicism - still a dominant trend - was heavily attacked by proponents of Romanticism, the Sculptures helped to reshape artistic taste as they represented a model different from abstract Roman art, being the leading example of the new naturalistic Grecian Gusto (Y. Hamilakis, 1999).

The admiration of European travelers for classical Greece often led to attempts to appropriate it, with the formation of private collections and the sale of antiquities culminating in the 19th century. As early as the end of the 18th century, the territories of the Ottoman Empire and the Italian peninsula were part of the Grand Tour, a monthslong journey of spiritual and aesthetic culture made by European nobles after completing their studies.

The French philhellene writer, politician and traveler, viscount François-René de Chateaubriand, who had already visited Greece in 1806, took a leading role in the Philhellenic Committee of Paris, publishing in 1825 his “An appeal for the sacred cause of the Greeks” ( Appel en faveur de la cause sacrée des Grecs) and the "Note on Greece”. Although in his Itinerary from Paris to Jerusalem, just three years after the looting of the monument, he comments caustically on the theft of the Sculptures by Elgin, he mentions:

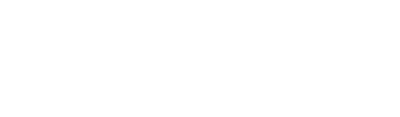

Descending from the Acropolis, I took with me a piece of marble from the Parthenon, as I had collected a piece of stone from the tomb of Agamemnon. And since then, I remove something from the monuments I visit, as a souvenir. Of course, they are not as nice as the ones snatched by Mr. de Choiseul and Lord Elgin, but they are enough for me.

Meanwhile, radical changes are taking place in Greece. The emerging new social class with European education and links with the western elites, discovered the heritage of their ancestors, cultivating self-awareness and participating in the creation of the community of the Greek Nation, a process that took on the dimensions of national rebirth. The looting of antiquities contributed to the awareness of the historical past. The establishment of the Greek state led to the systematic care, collection and study of antiquities, since they represented the visible material proof of the national continuity and were deeply integrated in the newly constructed national memory (Y. Hamilakis, 1999).

The Nobel Prize awarded poet George Seferis records it masterfully. The weight of the marbles hurts, but it is impossible to let it down:

I woke up with this marble head in my hands

that exhausts my elbows and I do not know where to put it down.

In his essay "A Greek - Makriyannis" (1981), G. Seferis highlights the famous saying of General Makriyannis in his Memoirs, which we often mention in public speech:

"I had two wonderful statues, a woman and a prince, intact - the veins were visible, they were so perfect. When they destroyed Poros, some soldiers had taken them, and in Argos they would sell it to some Europeans; they were looking for a thousand thalers... I gathered the soldiers, I told them: ‘Even if they give you ten thousand thalers, never accept for them to leave our homeland. That's what we fought for ".

"You understand, says Seferis. It’s not Lord Byron speaking, neither the most learned, nor the archaeologist; a son of a shepherd of Roumeli speaks with a body full of wounds. ‘That's what we fought for’. Fifteen gilded academies are not worth the value of this man’s words. Because only in such feelings can the education of the Nation take root and flourish. In real feelings and not in abstract notions about the beauty of our ancient ancestors or in dried hearts that have become obfuscated by the fear of the mass mob".

Panagiotis Kanellopoulos in the History of the European Spirit, points out that the Sicilian historian Xavier Scrofani, who visited Greece in 1794-95, fifteen years before Lord Byron, observed, like the latter, the continuity of the language with that of the ancients.

Reşid Pasha, also known as Kütahı, in 1826, besieged the Acropolis, where Greek fighters were holding cover. From his reference to the Sublime Porte, it is clear that he had realized the connection of Greek antiquities with the birth of national consciousness in the enslaved Greeks and their great contribution to the creation of the philhellenic movement in Europe, which will play such a decisive role in the course and final outcome of the Struggle for Independence (Th. Veremis, 2020).

The Bonapartist colonel, Olivier Voutier, narrates that in 1822, many fighters besieging the Acropolis of Athens chose to retreat, in order to stop the besieged Turks from demolishing the surviving parts of the walls and breaking the columns of the Parthenon to grab the lead of ancient binders, which was useful for casting bullets. With the mediation of Kyriakos Pittakis, later curator of Antiquities of the newly formed Greek state, Odysseas Androutsos stopped the destruction of the monument by supplying the Turks with bullets.

The first poetic response to the outbreak of the Greek Revolution did not come from Byron but from his younger contemporary and friend and one of the most important English romantic poets, Percy Bysshe Shelley. Shelley's enthusiasm for the flame of independence that prevailed in Greece prompted him to write in 1822, the lyrical drama Hellas, which he dedicated to Prince Mavrokordato. In the preface he states: "We are all Greeks. Our laws, our literature, our religion, our arts have their roots in Greece".

John Keats, one of the most beloved romantic poets, with a permanent presence in the British textbooks, a close friend of Byron and Shelley, inspired by the myths of classical antiquity in his widely read poem Ode on a Grecian Urn, written in 1819, reaffirms his belief in ancient Greek art as an autonomous body of humanitarian values, through an exemplary expression for the aesthetics of the 19th century.

The British Hellenist Jennifer Wallace points out that two events at the beginning of 19th century heralded the institutionalisation of Hellenism in the British establishment and the supremacy of Greece over Rome as a cultural and aesthetic model. First, when between 1801 and 1806 Lord Elgin removed all the sculptures from the Parthenon and shipped them to England to improve British taste, and second, in 1807, when Oxford introduced classical degree examinations. Greece and its culture were now considered essential elements for the moral education of the young and the touchstone for artists.

The reduction of classical antiquity as the cosmological cornerstone of Western European civilization had fundamental consequences in the recovery of national identity. The Sculptures of the Parthenon, being one of the most powerful landmarks of Hellenism, were to contribute decisively to the struggle of “paliggenesia” (regeneration).

Sophia Hiniadou Cambanis, is a lawyer specialized in public law and cultural management, Hellenic Parliament

* The text was based on the speech presented at the Conference "Political Patriotism and the Constitutions of the Greek Revolution", Theocharakis Foundation, 13-14.10.2021 and the article was also published in Ta Nea 15 November 2021.

Comments powered by CComment