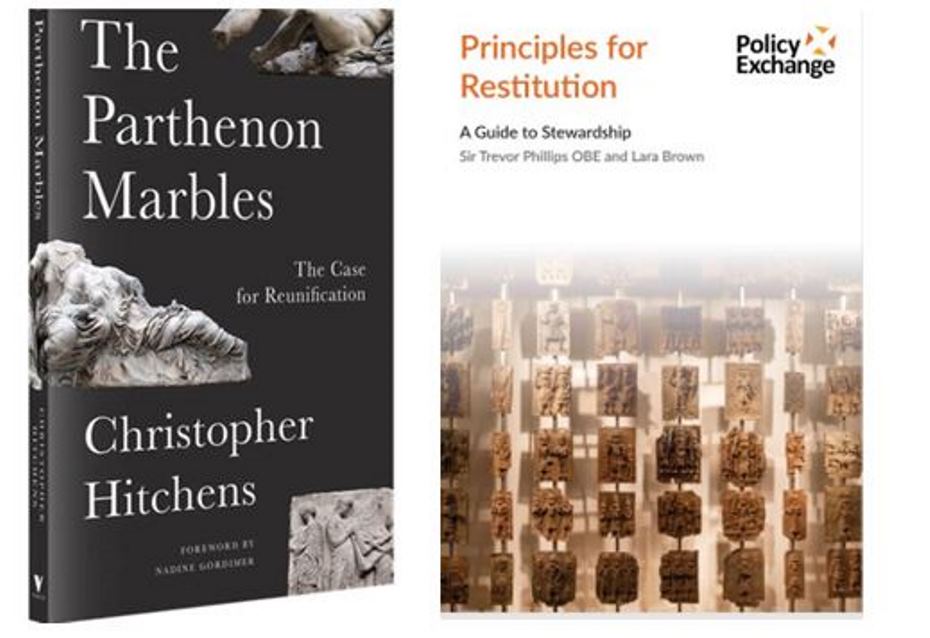

As more ancient treasures are returned to Greece, it seems the British Museum is losing its hold on its most famous disputed antiquities

Six Greek Golden Age utensils have been unveiled in the idyllic confines of Athens' ancient agora, thanks to the largesse of their former owner, the late and great classical historian Martin Robertson.

After years of being beseeched by Greek officials to hand over the fifth-century BC wonders - objects that adorned the sitting room of his Cambridge home for years - the British scholar has finally met the demand from beyond the grave. As of today, the black glazed wine jars are back in the place where they were excavated, gleaming in a glass case in the museum beneath the Acropolis.

Thrilled Greek officials can hardly contain themselves. Robertson's gift is the eighth such repatriation of antiquities removed from Greece in the past year.

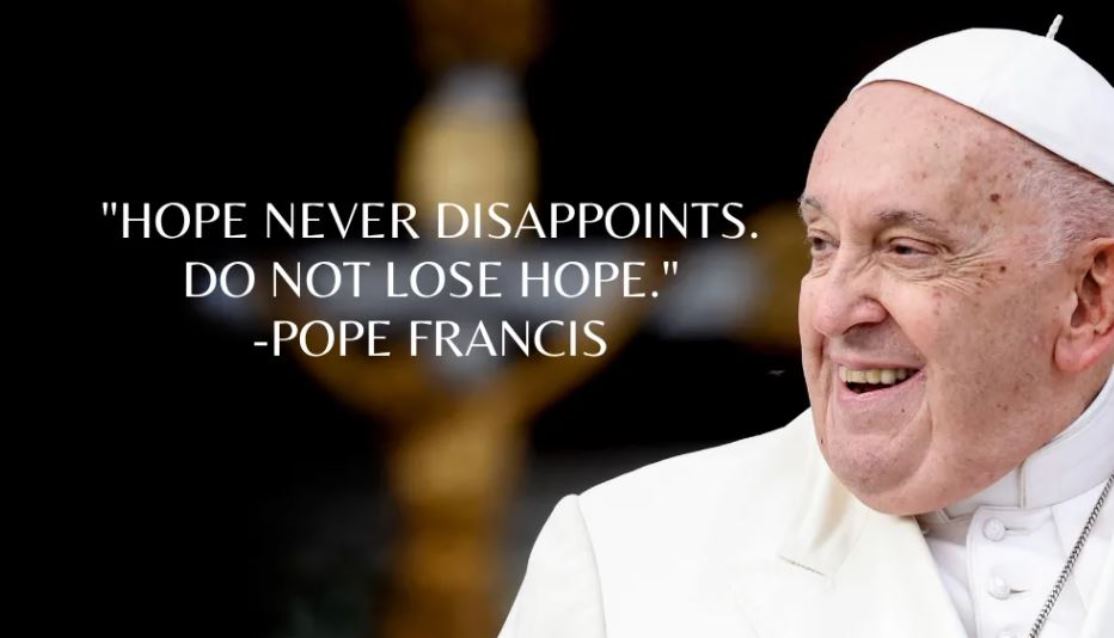

Most, including a piece of statuary sawn off from the Parthenon's northern frieze, have been returned with the excuse that they will be better housed "in context," in Athens' resplendent, new £94m Acropolis Museum. With international cultural policies radically altering attitudes towards contested antiquities, surely the time has come for the British Museum to finally relent on that most implacable of restitution dramas, the return of the Parthenon marbles?

After all, say campaigners, once the new Acropolis Museum is completed this summer, the moral pressure not to give them back will be irresistible. For the first time ever, Greece will have effectively destroyed the old claim that it is incapable of housing its Golden Age treasures. The new museum, whose great glass windows look up at the Parthenon, will be more eloquent than any number of legal to-dos over the rights or wrongs of London retaining the 88 fragments that once adorned the temple's monumental frieze.

That the British Museum is feeling the heat cannot be denied. Leaving aside the argument over whether Lord Elgin legally acquired the marbles in 1801, the argument that they are simply better off in London's Bloomsbury, divided and badly lit, is beginning to look absurd.

In this changing climate, the British Museum's refusal to even enter into negotiations with the Greek government also looks less than magnanimous. The Greeks have not only proposed that the British Museum open a branch in the new Acropolis Museum (effectively maintaining curatorship of the marbles) but have also offered a treasure trove of rotating exhibits in return.

The Greeks are also willing to consider allowing free access to the sculptures just like at the British Museum.

Neil MacGregor, the British Museum's director, has taken the unprecedented, and long-overdue, decision to announce in an interview on Tuesday that, in theory, London could loan the marbles to Greece - if Athens ended its refusal "to acknowledge that the trustees are the owners of the objects."

It's a small step - and one that MacGregor himself accepts, means little. But in a saga where every utterance counts, it may well be the beginning of a dialogue that, one day, just might resolve Europe's longest cultural row.