article from: http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2007/09/17/yale

Yale and Peru Reach Pact on Artifacts

Yale University has agreed that its extensive collections of artifacts taken from Machu Picchu almost a century ago are in fact the property of Peru and that many of them should return to that country. The agreement, which extends beyond the artifacts in dispute, promotes the idea of research collaboration between Yale and Peru and ends a bitter legal dispute over a prized collection.

Archaeologists, other anthropologists, and college museum directors — who have been closely watching the negotiations — applauded the outcome.

Several said that it could be a new model for resolving such disputes.

"Repatriation of objects from other cultures, most of which were acquired in the early part of the 20th century before important export rules and a focus on ethical and procedural standards for museum operations, will continue to be an issue," said Lisa Tremper Hanover, president of the Association of College and University Museums and Galleries. "Yale is setting an important example in working with Peru for the common goal of interpreting and sharing a cultural heritage. It should be a model for other institutions."

Added Hanover, director of the Philip and Muriel Berman Museum of Art at Ursinus College: "This is a good thing."

A joint statement from Yale and Peru announced these terms:

* Yale and Peru will co-sponsor an exhibition that will travel internationally, featuring objects the collections from Cusco and Machu Picchu. The exhibit will be curated by Yale and Peru's National Institute of Culture and will include additional pieces loaned by Peru.

* Peru, with advice from Yale, will build a new museum and research center in Cusco. The exhibition will be installed at the museum following its tour.

* Yale will acknowledge Peru's title to all the excavated objects, including the fragments, bones and specimens from Machu Picchu.

* Peru will share with Yale rights in the research collection, part of which will remain at Yale as object of ongoing research.

* Once the museum is ready for operation, the museum-quality objects will return to Peru along with a portion of the research collection.

The statement stressed that Yale and Peru would seek to promote research on a range of topics beyond the artifacts. "This understanding represents a new model of international cooperation providing for the collaborative stewardship of cultural and natural treasures," said the statement.

Yale ended up with thousands of objects from Machu Picchu, which had been unstudied for centuries when a Yale team — alerted by local farmers — started working there in 1911. Hiram Bingham III, who later became governor of Connecticut, led a series of projects that brought the artifacts to Yale. In 2005, Peru's government announced that it would sue Yale if the university did not return the artifacts.

Many universities and museums gathered up objects from developing nations and made deals to take the artifacts home. Many of these deals have attracted scrutiny over the years, as those giving permission to take objects were never briefed on the implications of what they were doing or weren't in a position to say No. Peruvian authorities have said that Bingham received permission to take the artifacts for up to 18 months for study, but that the artifacts were never intended as more than a short-term loan and that they should have been returned long ago.

Richard L. Burger, a professor of anthropology at Yale, said that the agreement included protections that would assure that current research isn't disrupted and that future research could include the artifacts.

"It's an agreement that is good for Yale and good for Peru," he said.

"It's a forward looking, and it's much broader than a question of items."

Alex W. Barker, who heads the ethics committees of both the American Anthropological Association and the Society for American Archaeology, said he was impressed with the way the situation was resolved. "Ethical standards are always evolving and, I hope, always improving, and deciding how to resolve disputes from earlier periods in which the ethical standards — not to mention the museum staffs and governmental representatives — involved were different is always hard," said Barker.

"There are no cookbook solutions. Open negotiation between the parties concerned is almost always the only workable and fair way to resolve such disputes."

Barker, who stressed that he was not speaking for the committees he leads, said that the Yale-Peru dispute and similar conflicts "go to the core issues of who controls the past."

The ethics committees consistently urge academic departments and museums to be "as transparent as possible" in discussing where collections came from and under what circumstances, he said. When departments or university museums come to the committees for advice, he said, it's usually because someone has advanced a claim against a part of a collection.

While it's hard to predict what impact the Yale agreement will have, Barker said that "any time a claim like this is resolved, it's going to lead to other groups seeing if they can make similar arguments."

He also noted that these disputes aren't just about whether objects are physically located in one country or another. "This isn't just about things that were carted off, but about how cultures are represented around the world," said Barker, who is director of the Museum of Art and Archaeology at the University of Missouri at Columbia.

Dean R. Snow, president of the Society for American Archaeology and a professor of anthropology at Pennsylvania State University, said that having these objects preserved in Peru was consistent with the way scholars in the field work these days. Most countries for decades now have been reluctant to let those running digs take their finds home. "So with rare exceptions, you work on the stuff you find in that country," said Snow.

The society's position, as a result, isn't to worry about where artifacts reside, but whether they are cared for and available to researchers. "The propriety of legal ownership is not something that we have been terribly involved with," Snow said. "Our interest is always in the resource itself — what's best for the resource, how to protect the collection."

The best thing about the resolution of the dispute may just be that it's over, Snow said. "It's good that it's settled and it's good that we had the discussions about this in the first place. This is not the kind of dispute to end in a nasty lawsuit," he said.

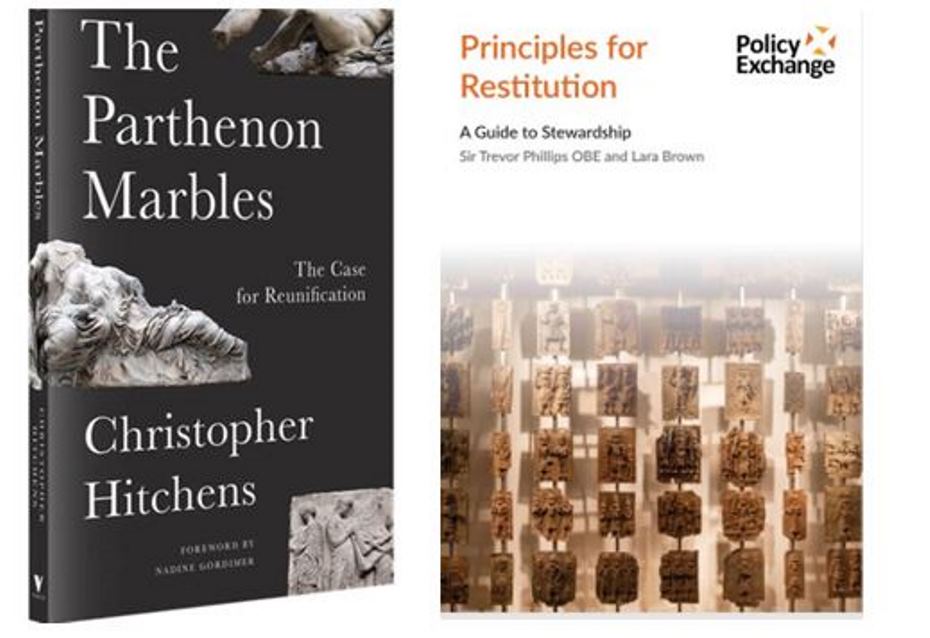

It's also important to remember, he said, that most of the work scholars do excavating abroad doesn't lead to famous museum pieces, such as the Peru collections at Yale or the Elgin Marbles, housed at the British Museum and long sought by Greece. The issues of access are still important on objects no one knows about — but most of these objects would never be fought over, Snow said.

"There's a real distinction between collections of museum quality and those that most North American archaeologists work with, which have very little museum quality but have scientific value," said Snow. "We're collecting soil samples. We're collecting dung samples. At the end of the day, after we've recorded the data, the best place for the original material might be a dumpster."

— Scott Jaschik