Yannis Andritsopoulos reports in Ta Nea on 21 September 2019: Britain has rejected Greece’s request to hold talks on returning the Parthenon Marbles after Athens proposed a meeting between experts from the two countries, it can be revealed.

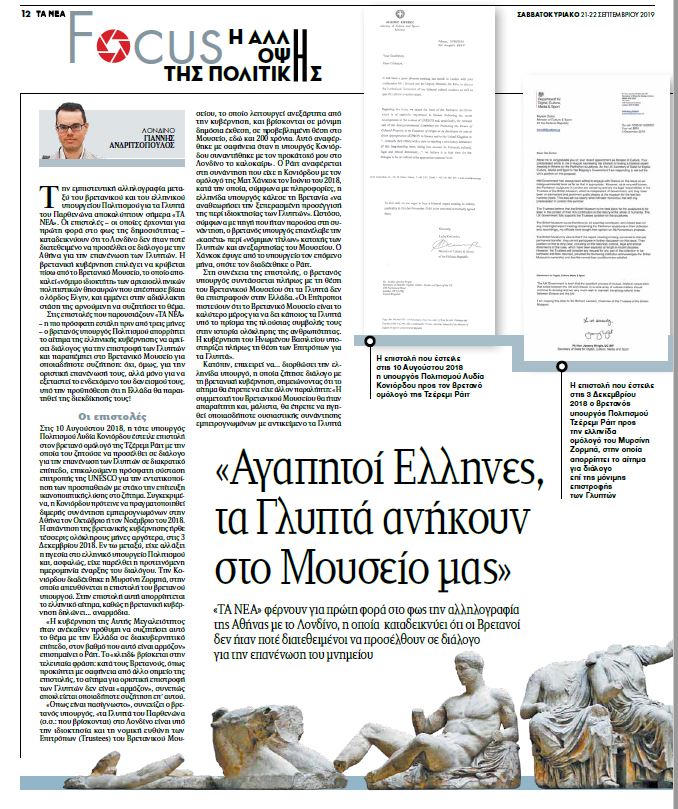

Ta Nea, Greece’s daily newspaper, has obtained a letter written last year by Jeremy Wright the then culture secretary, which states that the UK will not enter a discussion with Greece about the permanent reunification of the sculptures.

“If the expert meeting is being convened to discuss (the Marbles’) permanent transfer (to Greece), the British Museum cannot participate in further discussion on this issue,” the UK culture secretary wrote on December 3, 2018.

Wright was responding to a letter written by his Greek counterpart, Lydia Koniordou, in which she asked the British government to discuss the matter with Greece “at the appropriate interstate level”.

Koniordou sent her letter on August 10, 2018 and suggested that “a bilateral expert meeting” should take place in Athens “preferably in October or November 2018”.

However, Wright’s response to this request arrived four months later. His letter was addressed to Myrsini Zorba, who had since replaced Koniordou as Greece’s culture minister.

In his letter, the British culture secretary rejected Greece’s invitation, telling his Greek counterpart that any request regarding the Parthenon Marbles should be submitted to the British Museum rather than the British government.

“As is very well known, the Parthenon sculptures in London are owned by and are the legal responsibility of the Trustees of the British Museum, which is independent of Government, and they have been on permanent and prominent public display at the museum for the last two hundred years,” the letter reads.

Wright goes on to say that “the Trustees believe that the British Museum is the best place for the sculptures to be seen in the context of their rich contribution to the history of the whole of humanity. The UK Government fully supports the Trustees' position on the sculptures.”

Responding to Greece’s request for a bilateral meeting in Athens, Wright stresses that it is the British Museum, rather than the government, that should participate.

“The British Museum would therefore be an essential contributor, and indeed lead on any meaningful expert meeting concerning the Parthenon sculptures in their collection and, accordingly, my officials have sought their opinion on Ms Koniordou's proposal.”

However, the British Museum advised that it would not take part in such talks. Subsequently, the Greek government’s request was rejected by the UK government.

“The British Museum's view is that if the expert meeting is being convened to discuss permanent transfer, they cannot participate in further discussion on this issue. Their position on this is very clear, including on the historical, cultural, legal and ethical dimensions of the case, which have been explored at length in recent decades,” the letter reads.

Wright adds, however, that “the Trustees will consider any request for any part of the collection to be borrowed and then returned, provided the borrowing institution acknowledges the British Museum's ownership and that the normal loan conditions are satisfied.”

However, Greece insists that it is the rightful owner of the Parthenon Marbles. The Greek government says that the sculptures were illegally removed from the Parthenon during the Ottoman occupation of Greece in the early 1800s.

‘Deep cultural trauma’

Responding to Wright, Zorba sent her counterpart a letter dated May 30, 2019, in which she says that the ‘dismembered’ Parthenon Marbles “constitute an open wound to a World Heritage Site of the stature of the Acropolis. This is nothing less than a deep cultural trauma in the eyes of mankind.”

Zorba adds that “the return and-re-integration of the Parthenon Marbles remains a firm demand”, stressing that maintaining a dialogue on the issue is “an objective of major importance and of cultural responsibility towards both History and the moral order.”

“We would be willing to participate in it, provided it will not be rendered unrealistic through the insistence on such kinds of prerequisites. We call upon you to re-examine all of the facts, in order for us to be able to resume a well-meaning sincere dialogue, free from prerequisites or binding admissions and able to bear fruit in the future,” Greece’s then culture minister says.

The UK government has not responded to this letter. However, on June 10, 2019, arts minister Rebecca Pow wrote a letter to Dame Janet Suzman, Chair of the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles, in which she repeated word for word Jeremy Wright’s response to Zorba.

Dame Janet had previously written to Wright, saying that “the Government and the British Museum must attempt to show respect for the Parthenon and therefore also for its sculptures”.

“Keeping these very specific sculptures divided smacks of imperialism, an era we surely cannot continue to pay homage to without seriously re-considering the mood of the world we live in. Continued excuses not to reunite this peerless collection ring hollow,” she stressed.

Athens has repeatedly called for the permanent return of the 2,500-year-old sculptures that Lord Elgin removed from the Acropolis temple. The British Museum has consistently ruled out giving back the marbles, saying they were acquired legally.

“With an overwhelming sense of awe for the comprehensiveness of the collections in the British Museum, I yet cannot help being equally overwhelmed by its sense of superiority. The same rather smug ownership song is being sung,” Dame Janet Suzman told Ta Nea.

“Can the Director and Trustees not see that there is a different mood in the world? Can they not see that the Duveen Gallery is just one of a myriad of world exhibitions under its impressive roof?,” she added.

“Can they not admit that millions of their visitors find that they have entirely missed the Marbles due to other fascinations? In any case the visitor figures the BM gives out never indicate a figure for those who specifically visit the Marble galleries.”

“The New Acropolis Museum in Athens has an entirely more focussed task; it stands in sight of the Parthenon, and every floor of it is concentrated on the glories that were Greece. The spaces that should be filled by the BM’s Parthenon collection are a painful lacuna.”

“Every decent impulse for reunification should be awakened and seriously discussed by the both the BM Trustees and the British Government instead of repeatedly providing statutory replies. Depressingly they are not. When will they both wake from their Rip van Winkle-ish slumbers and realise the world has changed? The Empire is so very over.”

“Ex-Director Neil MacGregor himself says that the British think of their past in order to comfort themselves, whereas the Germans (he is a student of German history) reflect on their history in order to look to the future. They should start to emulate that honesty before another period of intellectual arthritis sets in,” Dame Janet added.

Published in Ta Nea, Greece’s daily newspaper (www.tanea.gr)

Publication date: 21 September 2019

English version: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/exclusive-uk-turned-down-greek-request-experts-return-andritsopoulos

Original version (in Greek): https://www.tanea.gr/print/2019/09/21/politics/agapitoi-ellinescrta-glypta-anikouncrsto-mouseio-mas/