Where best for the Parthenon Marbles? (LSE 17 October 2022), panel organised by the Hellenic Observatory (Professor Kevin Featherstone.) with Lord Ed Vaizey (‘Parthenon Project’) & Dr. Tatiana Flessas (LSE)

Thanks to Kevin Featherstone, to the Hellenic Observatory, to the audience both online and in person (esp. High Commissioner of Cyprus, Andreas Kakouros, an LSE graduate, in person).

I am an honorary citizen (epitimos dêmotês) of modern Sparti, but don’t have the honour to have been born a Hellene. I am, however, a devoted phil-Hellene, consciously following in the footsteps of Lord Byron, and for 60+ years I’ve been trying to turn myself into something as close as possible to a true Hellene. I started learning ancient Greek at 11, modern Greek at 23, I read Greats (Classics) at Oxford 1965-9, I completed an Oxford DPhil thesis on early Spartan archaeology and history under (Sir) John Boardman (1969-75), I taught ancient Greek history and archaeology at 4 universities, for over 40 years in all (1970-2014), I am currently A.G. Leventis Senior Research Fellow of Clare College Cambridge and President of the UK’s Hellenic Society. In 2021 I was lucky enough to be promoted Commander (Taxiarchês) of the Order of Honour (conferred by the President of Greece). But in tonight’s context I am above all Vice-Chair, BCRPM, and Vice-President, IARPS.

The British Committee (BCRPM) is almost 40 years old. It was founded in 1983 in response to the heroic initiative of Ms Melina Mercouri, then Culture Minister in Greece’s PASOK government. The BCRPM is now one of altogether some 19 national committees outside Greece. It was not however the first: that honour belongs to the Australian Commttee ( IOC-A-RPM) co-founded and chaired by Emanuel J. Comino (now 89, originally from the island of Kythera). The IARPS is rather younger, founded in 2005 and now chaired by Belgian archaeologist Dr Kris Tytgat. I am not sure whether I am actually a founder member of BCRPM, but I am certainly an early member, and well recall being invited to join, through my Cambridge (and Clare) colleague Prof. Anthony Snodgrass, and meeting with the likes of Eleni Cubitt, Prof Robert Browning, and MPs Eddie O’Hara and Chris Price, giants all.

My point is this: I’ve been actively campaigning for at first the ‘restitution’ and now the ‘reunification’ of the Parthenon Marbles/Sculptures back in Athens – all of them that still reside outside the Acropolis Museum, not just those in the BM – for almost 40 years. There’s no argument therefore or twist of argument for their retention outside Greece, esp. those in the BM, that I have not heard, all of them of course fatally flawed. On the other hand, I’ve been gladdened and heartened to watch over the years the steady – and lately far more lively and vigorous – growth of support for our reunification campaign, especially from among the ‘great British public’. I’ll come back to that. First, why the change in terminology from ‘restitution’ to ‘reunification’?

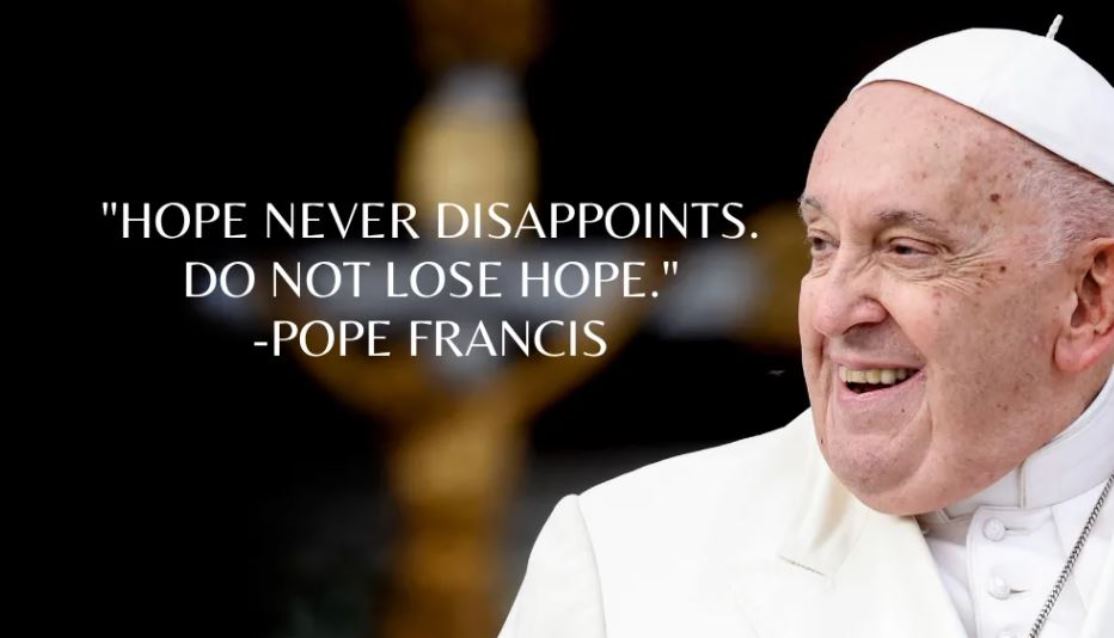

I’m no lawyer myself (though I happen to be surrounded by them at home), but it seems clear to me, as it always has been to BCRPM and IARPS, that ‘restitution’ has at least overtones of legalism and legality and therefore of ownership. I hardly need point out that all attempts to go down the legal route to reunification not only have manifestly failed in (or not in) the courts but have merely muddied the campaign waters, by raising precisely that ‘ownership’ red herring. I don’t mean to imply that the legal issue of Lord Elgin’s and so the British state’s and so the British Museum’s title to the Marbles is not important. It is. Indeed, I’ve just been reading in draft a wonderful forthcoming book by a French human rights lawyer to the effect that in international law the UK probably does not have much of a case. What I do mean by called ownership a red herring is that we campaigners should steer very clear indeed of resorting to legal argument or action in the present and for the future.

To be very personal for a moment: I was very kindly sent personally by Mr John Lefas (founder and funder of the Parthenon Project) a copy of Who Owns History? by Geoffrey Robertson (then) QC. That was in 2019, but I confess I couldn’t bring myself to read it then, as I was too upset by Mr Lefas’s and Mr Robertson’s involvement in (costly and fruitless) legal action. Instead, I clung on all the more fiercely to (my Oxford contemporary and fellow activist) Chris Hitchens’s The Parthenon Marbles, which in its 3rd edition (Verso, 2008) came with a Preface by Nadine Gordimer and excellent essays by Robert Browning (on the chequered history of the Parthenon as a building over the centuries) and by Charalambos Bouras (on restoration works conducted since the mid-1970s).

Why did I choose to join and campaign actively for the BCRPM all those years ago? Why do I choose still actively to campaign? Before I state them, I would like to emphasise that my reasons, being those of an academic with skin in the game of Hellenic cultural history over many years from antiquity to modernity, will not necessarily coincide completely even with those of my fellow BCRPM members. They are basically two (or three). First, moral-imperative; second, academic-aesthetic. The context and the main act of removal of Parthenon Marbles from Athens (by Lord Elgin and his cohorts from 1801) did not then and does not now reflect well on the standing of Britain as a sovereign nation – as Greece of course in the early 19th century was not.

It is to this day a shameful nonsense that not only do large parts of an original whole (the unique frieze) remain divided between London and Athens but that even individual sculptural members (a metope, say, or a pedimental sculpture) still are too. Members which, I must stress, are not ‘merely’ art objects – as if carved by Pheidias for display in an ancient Uffizi – but much much more than that (especially as regards their original religious-political dimension). Then, there is the wider, deeper, altogether even more problematic issue of politics – not academic politics, but governmental, and interstate, cultural politics. For reunification will require eventually at least one Act of the UK Parliament, and I need hardly remind this academic audience that it behoves us, as a (still, just) liberal-democratic polity in an increasingly un- or anti-democratic, illiberal world, to promote soft, cultural, interstate diplomacy in every positive way we possibly can.

Towards which goal I detect a number of promising straws in the recent wind. The latest yougov. poll. The return of Parthenon fragments from Heidelberg and Palermo (though not yet from my own Cambridge). The recruitment of several prominent journalists to the reunification campaign. The success of the parallel Benin Bronzes and other (imperial/stolen) African objects repatriation campaigns, especially in France (itself once, like Britain, a colonial/imperial power, indeed a once competing power – hence, in significant part, Elgin’s ability to loot, plunder and destroy as he did). The latest (November 2021) UNESCO resolution on cultural property. Finally – and by no means least – the Parthenon Project and its ‘front man’ Ed VaIzey, himself a recent convert to the reunification cause (echoing the published views of a couple of former BM Trustees). Lord Vaizey’s very recent debate in the UK House of Lords focused quite rightly on the National Heritage Act of 1983 and rightly provoked several comments to the effect that we in Britain must do ‘the right thing’ by the Marbles.

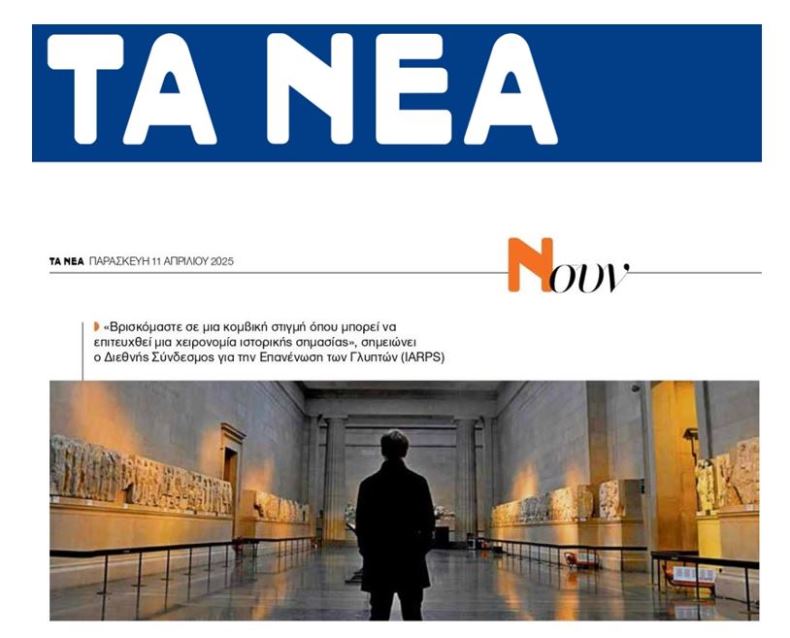

Two final points. First ‘Parthenon Marbles’. To clear up any possible confusion, it really is the repatriation of only the marbles/sculptures wrenched from one particular building (still there) on the Acropolis of Athens, the Parthenon, that the Greek Government – and therefore BCRPM and IARPS – are requesting, in particular of the BM. Don’t get me wrong – I too love much of the BM (though I am sometimes tempted to call it the British Imperial War Museum). But quite apart from their holding on to the Parthenon Marbles illicitly and immorally and quite probably illegally, the Trustees – and Curators - are guilty of mounting a simply disgraceful display in the (infamously named) Duveen Gallery. Ironically, just how wrong and how bad it is (and always has been since 1962) was brought home to me by my Cambridge colleague, Dame Mary Beard, in her excellent little 2002 Parthenon book. Ironically, because she just happens now to be a BM Trustee.

Final final point. Oh – I nearly forgot… to answer the question posed by this LSE debate. ‘Where best for the Parthenon Marbles?’ It’s a no-brainer. In the newish (founded 2009) Acropolis Museum. The clue is in the name. The Parthenon is a building essentially of as well as on the Athenian Acropolis. In Athens, in the dedicated Parthenon Gallery of the Acropolis Museum the remaining Parthenon sculptures that the Museum holds are arranged so that they face outward, as they have always done. Their alignment is accurate, they are bathed in Athenian light, and viewed against the Parthenon itself and the Acropolis. At night, the glass surfaces of the Museum afford dynamic comparisons, reflecting the sculptures against the illuminated Parthenon and Acropolis. In the Acropolis Museum, and only there, it is possible properly to understand and appreciate the sculptures close to their original environment, where light, clouds, rain, and outcrops of marble all add to the story. In Athens, moreover, visitors approach the sculptures in a correct sequence, having been prepared for the ultimate glory of the Parthenon by first traversing and viewing up close works that both reflect and encapsulate the whole connected history of the Acropolis up to the Parthenon’s date, the latter half of the 5th century BCE.

Professor Paul Cartledge, Vice-Chair of BCRPM & IARPS