Following the success of the newly opened Acropolis Museum, Greek officials are more determined than ever to retrieve their missing heritage.

For as long as most Athenians can remember, the intersection of Makriyianni and Dionysiou Areopagitou streets was a nondescript place, the preserve of those bent on illicitly parking their cars on the narrow alleys of the historic Plaka district.

Nine days after the opening of the New Acropolis Museum, this little slice of Athens at the foot of the Acropolis rock is a place transformed. Where vehicles once clogged the streets, there are street cafes, people and performance artists – Greeks such as Anita Papachristou who, like a modern-day pilgrim, makes a point of dropping in to behold the behemoth that looks set to become Greece's 21st-century shrine. "We waited for it long enough," she says, looking up at the honey-coloured Parthenon marble, illuminated along the length and breadth of the museum's upper floor. "And now that it's here, I can say it's been worth waiting for."

The smell of cement still pervades the corridors and stairwells of the three-storey, €130m museum but neither that, nor the scouring Athenian heat, has stopped it being a sell-out success. At what will go down as the museum's first post-opening press conference (held in a leather-seated auditorium in the bowels of the building) yesterday, Greek officials could scarcely contain their excitement at the "scandalous" number of ticket sales, both at home and abroad.

In the first five days, some 55,000 people rushed to snap up tickets that until the end of 2009 will sell at €1 a piece. Internet interest has also been unexpectedly high, helping to boost the sense that with this new showcase, Athens is on to a winner to retrieve the Parthenon sculptures from the British Museum. "Altogether, 90,822 tickets have been sold," said the Greek culture minister Antonis Samaras. "From America to Mongolia, Australia to Nepal, internet users have logged into the [museum's] site. I, personally, have received letters of thanks from ordinary people in China. The interest has been phenomenal."

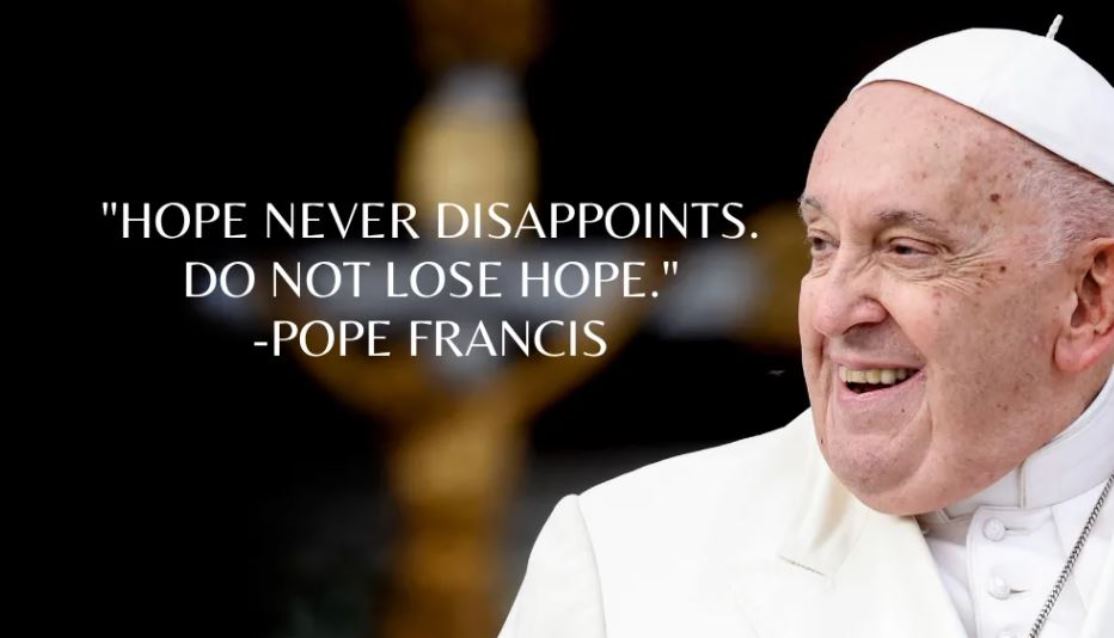

It's been more than 30 years in the making, and many Greeks thought they would never see the museum rise from the archaeologically rich but controversial ground on which it now stands beneath the ancient Acropolis. Politicians with an eye to posterity, starting with Melina Mercouri – the late actress who initiated the campaign for the return of the marbles in 1981– were more optimistic. By the time the partly EU-funded building was under construction, Greek officials were arguing as never before that the museum would reinvigorate the movement to win back those parts of the Parthenon frieze that Lord Elgin "hacked, prized and looted" from the monument more than 200 years ago.

Yesterday, as they hit back at the British Museum's longstanding argument that Athens has nowhere decent enough to house its Golden Age Wonders, Greek confidence had never been higher. There were not only the numbers, or the polls (including the Guardian's this week), that proved most Britons were now in favour of the contested masterpieces returning to Greece, there was also the "moral argument", said Samaras. "The museum has created a strength, a power in its own right for their return," he added, describing the demand for their repatriation as "universal" and ruling out that Athens would resort to the courts to retrieve the sculptures from Britain.

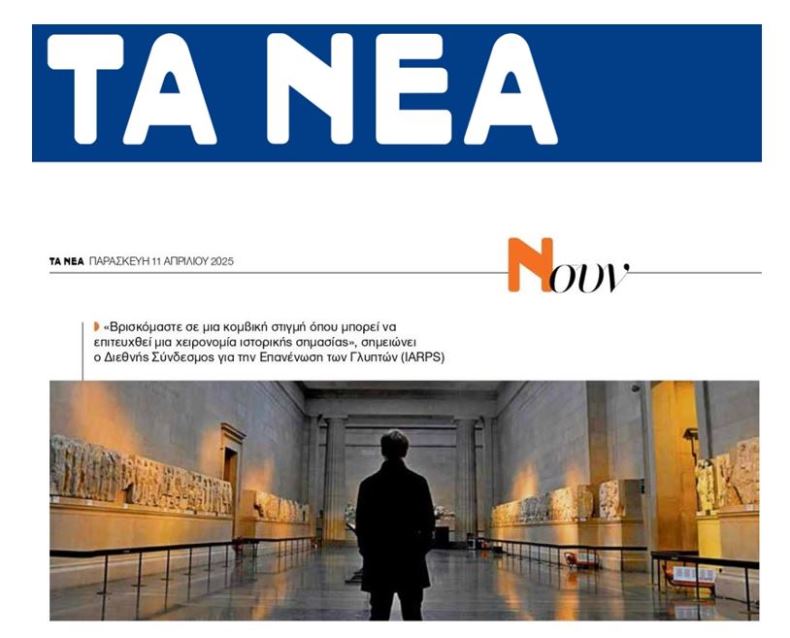

"It is a question of ethics. Times have changed. Museums including the [New York] Met have returned disputed artworks to their country of origin." If anything, say Greek classicists, the new museum's popularity has finally proved that people want to see the treasures not only in context, beneath the temple where they were carved, but as a "narrative whole", depicting the uninterrupted story of the 106-metre-long Panathenaic procession. In place of those pieces currently held in London, Greek archaeologists have placed crude, alabaster white plastercasts acquired from the British Museum in 1840. In the unforgiving attic light that filters through the museum's huge glass panes, they stand out like eyesores.

So, is Europe's longest-running cultural row about to get even more bitter? The Greeks made a point of keeping the museum's opening ceremony low-key to avoid "contaminating" an otherwise joyous event. Little was made of the fact that only two trustees from the British Museum flew in for the bonanza, even though international debate over ownership of the marbles was revived on the eve of the inauguration, following talk of Britain loaning the marbles to Athens.

But now Greek officials say the gloves are off and, yes, it will get ugly. "We are no longer willing to play the nice guys," says a senior member of the culture ministry, who is masterminding the government's strategy on the issue. "The British Museum has lost the argument. It is now on the defensive. In a year's time, I can assure you, it will want to give the marbles back."

If the marbles are not returned home soon, private Greek investors apparently have hinted that they will build a Madame Tussauds-like museum down the road, with Lord Elgin hacking the sculptures from the monument as its main exhibit. Presently, the story is doing the rounds as a joke. But the bets are on that it may well happen. And if it does, it will be no laughing matter for the British Museum.