Greece has cut the €6m budget for the festivities to mark the June 20 opening of the new Acropolis museum by more than half as recession looms over its economy.

But a ticket to see the 2,500-year-old sculptures from the Parthenon and other temples on the Acropolis hill will cost just €1 this year - the same price as a journey on the subsidised Athens metro. By comparison a ticket for Paris's Louvre costs €9, or €14 ($19.56, £12.34) to include temporary exhibitions, and New York's Metropolitan Museum charges $20 (€14.20, £12.60).

"A global recession isn't the time for a big fireworks display, but we want everyone to be able to visit," says Antonis Samaras, culture minister.

Yet in spite of the cuts, the gala opening still includes an official dinner at the museum for visiting heads of state and government, worldwide television coverage and a high-tech show in the sculpture galleries.

The Greek economy is projected to shrink by about 1 per cent this year, according to the International Monetary Fund. Years of excessive spending have pushed up the public debt to almost 98 per cent of gross domestic product.

The government has not made public the extent of cost overruns on the €130m museum, an austere glass and concrete block designed by Bernard Tschumi, a Swiss architect, and Michalis Photiadis, his Greek associate. Its construction took almost 10 years as Byzantine-era ruins found on the site had to be excavated and the ground floor redesigned.

Mr Samaras said Greece would not make a request during the festivities for the Elgin marbles to be re-turned, although Costas Karamanlis, the prime minister, has said its completion would mark "the time for the marbles to come home".

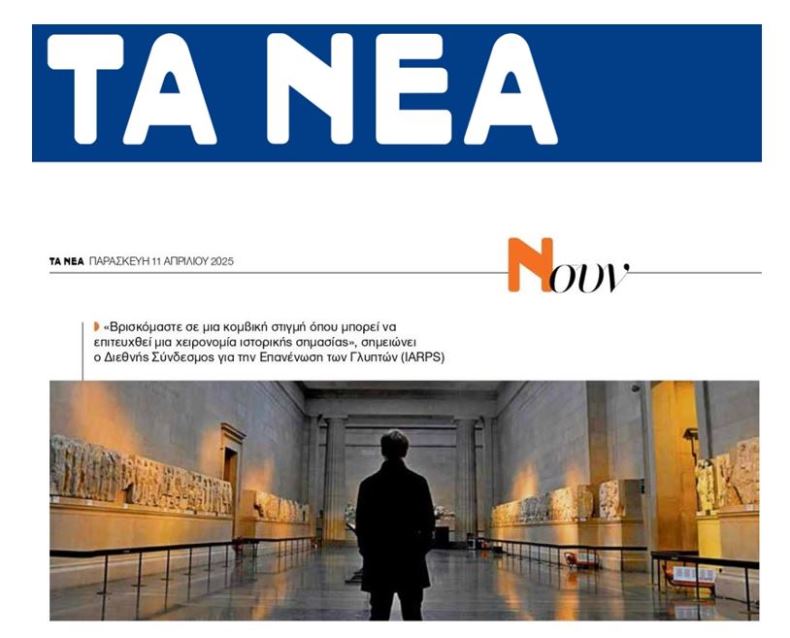

About 40 per cent of the 160m-long frieze from the Parthenon, removed in the early 19th century by Lord Elgin, a British diplomat, is on show in London's British Museum. The museum says it was legally obtained.

Greece's own section of the frieze is displayed in the new museum's top-floor gallery, which replicates the dimensions and orientation of the Parthenon. "Our strategy [on the Parthenon sculptures] hasn't changed," Mr Samaras said. "The presence of thousands of visitors to the new museum will send its own message."

In the past three years, both Heidelberg University and the Italian government have returned fragments of sculpture taken from the Acropolis temples.

Dimitris Pandermanlis, chairman of the state-controlled company responsible for building the museum, said it could cater for 10,000 visitors a day.