"Forgive me, it is crazy," says Professor Dimitrios Pandermalis, president of the Organisation for the Construction of the New Acropolis Museum, explaining why he has kept me waiting for almost half an hour in the museum's spacious reception. Pandermalis is the elderly, dignified archaeologist at the centre of the latest - and the Greek government hopes concluding - chapter in the saga of the Parthenon/Elgin Marbles, and the pressure is beginning to tell. "I hate all this publicity," he says. "This is not my job, but I have to manage it."

Beware Greeks bearing gifts. An adage I should have borne in mind before accepting an invitation to be the first journalist to be allowed to see the museum's completed galleries, and the first person to photograph the inside of the airy glass box at the top of the museum which will house the part of the Parthenon Marbles held by the Greeks. This is a rare privilege, but it also means being drawn into the seemingly endless controversy that has raged since Lord Byron savaged the seventh earl of Elgin for removing large chunks of the statuary from the Parthenon in the first decade of the 19th century - a cache that ended up in the British Museum a decade later and has been a source of resentment in Greece ever since. The Greeks may hope their splendid new museum - which has been almost 40 years in the planning (twice as long as it took for their ancient forebears to build the Parthenon) and cost €130m - will bring the issue to a head, but the portents are not good.

The new museum, designed by the Swiss-American architect Bernard Tschumi and just a few minutes' walk from the Acropolis, is meant to demonstrate once and for all that the Greeks could look after the sculptures as well, if not better, than the famous institution that has housed them for close on two centuries, ever since the bankrupt Lord Elgin sold the works he had taken from the Parthenon to the British government for £35,000 in 1816. Before the great strategic issues can be dealt with, however, Pandermalis has earthier concerns. The wiring, for a start. "We told the construction company about this a year ago," he says, as we pass a group of workmen who are adjusting cables, "and they leave it until the week before the opening." Men are up ladders peeling plastic off 2,500-year-old sculpted tablets (called metopes); young women are giving a final wash to small replicas of the statues which originally bookended the Parthenon; the gift shop is an empty shell. But the professor insists all will be ready for the official launch by the president of Greece on Saturday.

The museum is entered up a ramp that faintly echoes the slope up to the Acropolis. On the first floor are arrayed the gorgeous statues of the pre-Parthenon period - principally from the sixth century BC, when the Acropolis was already well established as the centre of the city's cultural and religious life. The old temples were swept away by Persian invaders in 490BC, and 40 years later the Athenians - at the height of their power - embarked on the building of the Parthenon, which was to serve as the home to a 40ft golden statue of the goddess Athena (made of wood and ivory, and lost in the fourth century AD) and as a treasury. Ancient Greeks had no qualms about mixing religion and money.

Ancient Athens lies at the root of western culture, yet the battles over the marbles that once adorned the Parthenon have been far from civilised. Could the city's new Acropolis Museum offer a fresh beginning? Stephen Moss gets an exclusive preview

The sculptures from the Parthenon itself are housed in the glass gallery above. It has the precise dimensions of the Parthenon, is oriented to face it directly on the hillside opposite, and attempts to recreate the outer series of metopes showing mythological battles and the inner frieze depicting a procession of Athenians paying homage to Athena. The new gallery combines the sculptures held in Greece with plaster casts of those held in London (there are also smaller holdings in the Louvre and several other international museums, all of which Greece wants returned). Even some individual statues are divided between locations. On one, a single hand is picked out as a white plaster cast. The body is in Athens; the hand resides in Munich. But initially the Greeks' attention is on London and the British Museum, which has half of the surviving sculptures. "Everybody asks, 'How can it be that this figure is half London, half Athens?'" says Pandermalis.

Some of the statues and reliefs have been lost completely, and gaps have been left to show what cannot be located anywhere. What can be gathered together is a crucial question in settling whether the marbles should be returned, and there is a staggering disparity between the two sides. Pandermalis says that if everything came back, more than 85% of the original could be reconstituted, but this is disputed by the British Museum, which says that half the metopes, a third of the frieze and more than half of the statuary that adorned the pediments at each end of the temple are lost. If Pandermalis is right, there would be a strong case for bringing all the material back together; if the British Museum is right, the Greek case is much weaker.

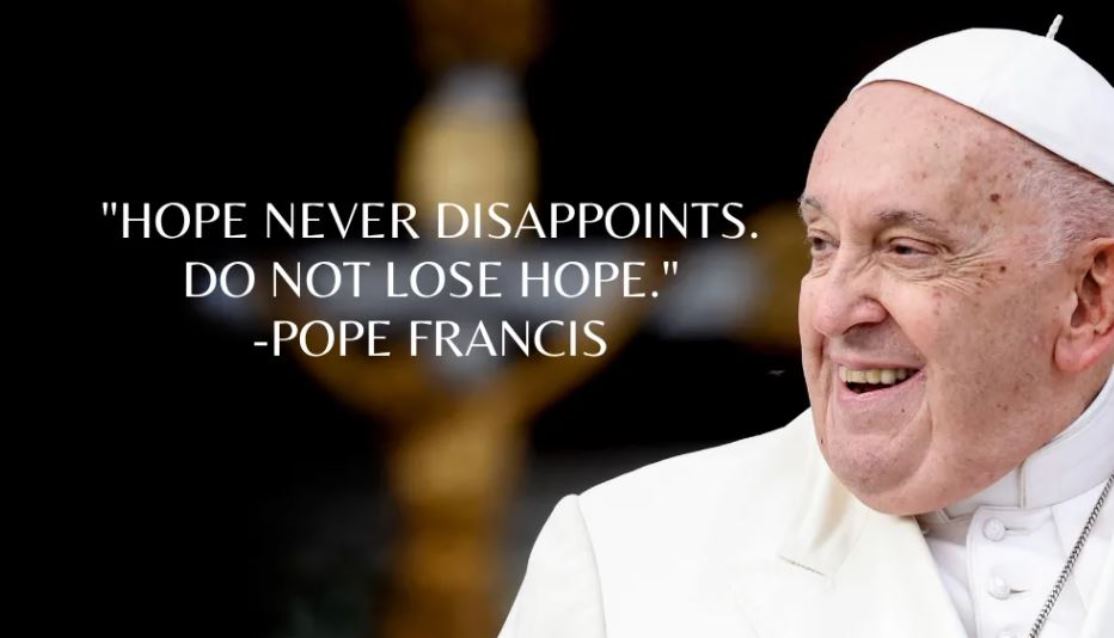

This is art by numbers, but these numbers count. Those who favour returning the Elgin Marbles to Athens tend to skate over what has been lost. Take Nadine Gordimer, who has contributed the preface to a new edition of Christopher Hitchens's book, The Parthenon Marbles, a typically vigorous argument in favour of repatriation first published in 1987. Gordimer seems oblivious to the fact that Elgin was further wrecking something that was already wrecked - much of the material he brought back was not hacked from the building but had already been blown off in 1687, when the Venetians attacked the Parthenon (unhelpfully, the besieged Turks were using it as an ammunition dump). She also assumes, erroneously, that the British Museum, by releasing what it holds, would magically return at least the frieze to its original form. "Coherence can and must be restored," she writes, in a passage stronger on rhetoric than fact.

Hitchens is guilty of the same error. "Picture the panel of the Mona Lisa, if it had been sawn in half by art thieves during, say, the Napoleonic wars," he writes in the introduction to the new edition. "Imagine the two halves surviving the conflict, with one ending up in a museum in Copenhagen and the other in a gallery in Lisbon. Would you not be impatient, not to say eager, to see how the two would look when placed side by side?" Perhaps, but does our fascination wane if the middle third is missing? How would we feel about the Mona Lisa if we had the top of her head, her body and her hands, but were missing her enigmatic smile?

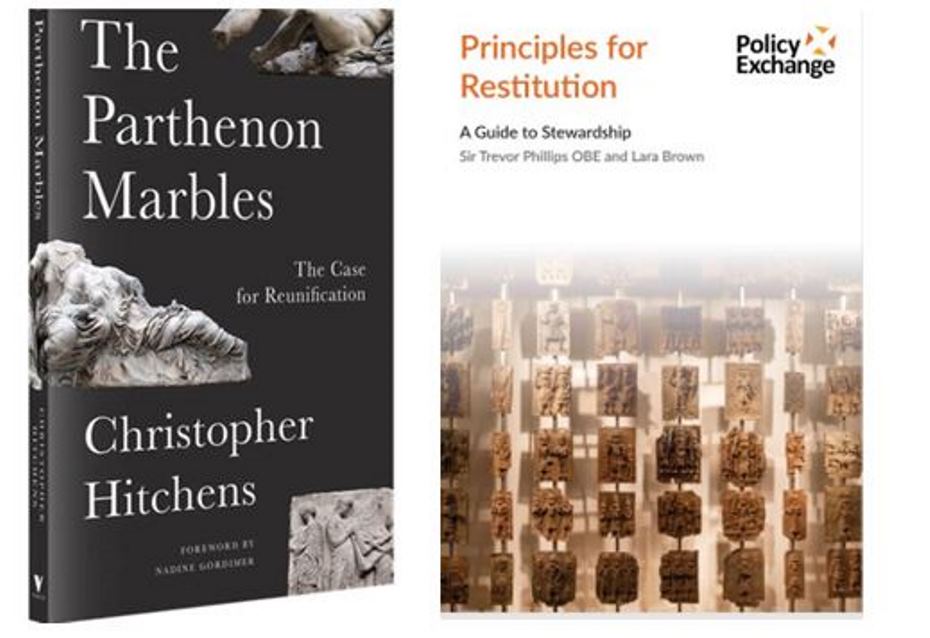

As Pandermalis is showing me around the gallery, the Greek minister of culture, Antonis Samaras, arrives. Samaras, a sleek, self-confident figure with a politician's firm handshake, is excited by a story playing in that day's Greek press that suggests the British Museum is willing to accept the possibility of a loan of its marbles to the new museum in Athens if Greece renounces ownership of them. Such a renunciation, he says, is unacceptable, but he still sees the offer as a constructive step. In the 1980s, when the film star Melina Mercouri was culture minister, the campaign for the return of the Elgin Marbles was based on tearful emotionalism; now, in the hands of professional politicians such as Samaras, it is about sharp-suited wheeler-dealing.

Samaras says the Greek government would never accept such a precondition. "It would be tantamount to accepting that what Elgin did was right. It would be like legalising or sanctifying his deeds, and I don't think any Greek government would ever do that." He sees the suggestion as a tactic, designed to divert attention from the fact that the new museum has changed the terms of the debate. "The museum is creating huge momentum, a crescendo all over the world, including England, where public opinion favours the return of the marbles." But he also believes it may signal a change of mood in official circles in the UK. "It seems that, for the first time, the British are starting to see room for serious discussion."

The Greeks are placing a heavy burden on the marbles' gleaming new home. "This museum is a museum of symbols and ideas," says Samaras, "and the whole world will come. That creates pressure on its own. On top of that, you have other museums, such as the Vatican, Palermo, Heidelberg, that are sending pieces back. Our goal was to have the best museum in the world, and that negates the British argument that we don't have a place to store them."

So will Greece get its marbles back? "This is a new beginning," he says with that politician's ear for the grand-sounding phrase, "and this is something that not just the Greeks want; I believe it will be the whole world. What we're doing here is unique, and from what we see in the museum stems everything that came out in western culture. The pressure will mount. There are 25 committees all over the world asking for these pieces to come back. It would mean a lot for the Greek people. It's 207 years [since they were taken]; that's a long time."

Out on Makrigianni Street, which runs alongside the museum and is being scrubbed hourly in anticipation of the opening ceremony, there is a popular upswelling of feeling in favour of the marbles being "reunified", to use the word the Greeks favour. Gift shop owner Costantinos X Zacharopoulos - the X is important because his father and 11 of his uncles are also called Costantinos - is friendly but firm. "If you were Greek, what would you say? They should come back, they belong here."

Nicholas Avgeris, the young barman at the Elaia Bistro, is even more adamant. "Something that belongs to Greece should come back to Greece," he insists. "If we had Stonehenge, I'm sure you would want it back. Give them back and show the world that you are not thieves ... Sorry, find another word for thieves. We don't think you are thieves."

None of these forcefully held opinions will carry much weight in the UK. Greece invited the Queen and Gordon Brown to Saturday's opening. Both are otherwise engaged, and instead Britain will be represented by Bonnie Greer, the deputy chairman of the British Museum's board of trustees, and Lesley Fitton, keeper of the department of ancient Greece and Rome. Let's hope our two plenipotentiaries are not taken hostage.

The British Museum denies any offer of a loan has been made. Its spokeswoman, Hannah Boulton, says an interview she gave to the Athens-based Skai Radio has been misinterpreted. "I was asked some general questions by Skai about the museum's attitude to lending," she says. "I said that, in principle, trustees are always happy to consider any loan request, but that an essential precondition is recognition of the museum's ownership. I was talking hypothetically, but this was conflated into an offer. In any case, the Greek government don't recognise our ownership, which makes any discussion of lending virtually impossible."

When I contact the Department of Culture, Media and Sport to ask whether the opening of the new museum will make a difference to the UK government's attitude, I am surprised by the uncompromising reply. "Neither the trustees nor the British government believe they should be returned," says a spokesman. "They are available free of charge in a museum that has more visitors than any other in the world; they are looked after in perfect environmental conditions; and above all they are presented in a world context and seen alongside comparative civilisations." Will they ever be returned? "Never say never, but I can't imagine the circumstances will ever change. There have been landmarks along the way - the 2004 Olympic games in Athens, now the new museum, junctions where the arguments became more compelling - but we resisted them then and that is likely to continue to be the case. There is not so much as a chink of hesitation in the government's position."

Why does the British Museum refuse to give way? "The question is, 'Do you believe in the value of a worldwide collection here?'" says Boulton. "If you agree with that first principle, then whatever you may think about the way material has been acquired in the past is secondary to that fundamental purpose." Ian Jenkins, senior curator in the department of ancient Greece and Rome and the world's leading expert on the sculptures, says the two museums serve different functions. "In Greece, the sculptures can be viewed as part of the history of Athens and the Acropolis; here, they can be seen as part of a world history."

Mary Beard, professor of classics at Cambridge University and author of a brilliant book on the Parthenon, takes what she calls a "principled fence-sitting position". "I'm on the fence, but I see that as quite a positive place to be," she explains. "It's not just that I can't make my mind up. Why is this controversy important? Because it raises issues about how we deal with world culture and globalism. How do we handle monuments that have global significance? There's hardly any country in the world where, if you showed them an outline of the Parthenon, people wouldn't be able to recognise it. That can't belong to one country."

Beard's views are complex, but a key part of her argument is that the Parthenon is a building with 2,500 years of history that, at different times, has been temple, bank, Christian church, mosque, barracks, sanctuary, ammunition dump and ruin. It is now far less of a ruin than it was a century ago. Who knows, perhaps one day it will be rebuilt so it matches the splendour of the full-scale replica constructed in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1897, which comes complete with a 42ft golden statue of Athena. But Beard is suspicious of attempts to fix the Parthenon in the middle of the fifth century BC, to pretend the Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman empires never existed, to recruit the building and the sculptures to the Greek nationalist cause.

Like it or not, even Lord Elgin is part of the marbles' history; the controversy has stoked the Parthenon's fame. Without Elgin, Athens' new museum would not now be about to open to a worldwide clamour. Byron was wrong when he damned Elgin as a "dull spoiler"; the earl was the Max Clifford of classical Greece. Beard, a notable contrarian, also says she would be very happy for the Greeks to have Stonehenge, which she finds "boring". Here at last, perhaps, we have the beginnings of a solution.