Picking up the Parthenon pieces

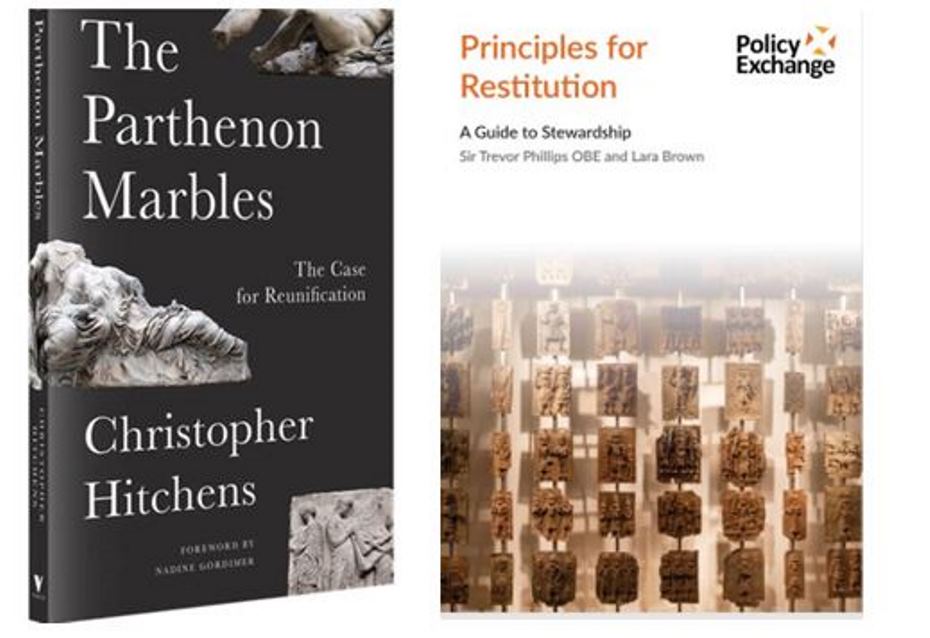

On a recent visit to Stockholm I heard how the marvellously energetic Swedish Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles have on two previous occasions returned to Athens small fragments from the Parthenon that had been picked up as souvenirs by Swedish nationals during visits to the temple many years ago.

Their 'owners' had evidently suffered a crise de conscience prompted, it seems, by the growing international tide of opinion that favours the return of the Parthenon Marbles still held in London. Last June the Vatican returned a piece, as did Italy last October .

In both the Swedish cases the small fragments were gratefully accepted by the archaeological authorities in Athens. Cynics might argue that these minor acts of restitution are more symbolic than functional since we're talking here about the kind of object that can be fitted into a suitcase or hand luggage rather than large architectural members. But let's not underestimate their symbolic value nonetheless, for they could end up having a functional value too. It is acts like this that illustrate the extent to which international attitudes towards cultural property are changing, not at an elevated bureaucratic level but where it really counts among the people, the demos.

Nobody is arguing that it could ever be possible to fully reunify the Parthenon. But the notion that every year pieces are returned to Athens from around the world be they tiny souvenirs collected during less enlightened times by innocent tourists wandering around the monument or more significant pieces acquired by museums in the great era of collecting in the nineteenth century demonstrates that not everyone shares the views promulgated by acquisitive directors of encyclopedic museums.

This week it emerged that two US tourists who chipped off a piece of the Colosseum in Rome 25 years ago have returned it, along with an apology for taking it . Like the pieces of the Parthenon recently returned to Athens, the bits of the Colosseum were small enough to fit into a pocket but they clearly grew in size in the minds of their owners whose conscience eventually got the better of them.

Inside the package from California was a note that read: "We should have done this sooner." According to one news report, Rome's archaeology officials have accepted the couple's apology and the local tourism officer has invited them to return to the city.

"Every time I looked at my souvenir collection, and came across that piece it made me feel guilty," wrote the Californian collectors. "It was a selfish and superficial act." Those are sentiments that the majority of British people feel whenever they wander into the Duveen Galleries in the British Museum in London, but they are powerless to act.

If Athens made an appeal to the world to return even the smallest souvenirs picked up from the Parthenon, it would increase pressure on the British Museum to return the Parthenon Marbles held in London. After all, in terms of motivation, there is little if any difference between the Californian couple who picked up fragments from the Colosseum and squirrelled them home, and Lord Elgin hacking off major sections of the Parthenon in the hope of adorning his ancestral seat.

Both acts were ethically wrong.One of them has been righted; the other has not.

Tom Flynn

www.artknows.co.uk