Let’s keep going and raise awareness that while we might not have huge resources, we’re open to returning ancestors and belongings home.

Amy Shakespeare is an AHRC-funded PhD researcher at the University of Exeter and a freelance consultant

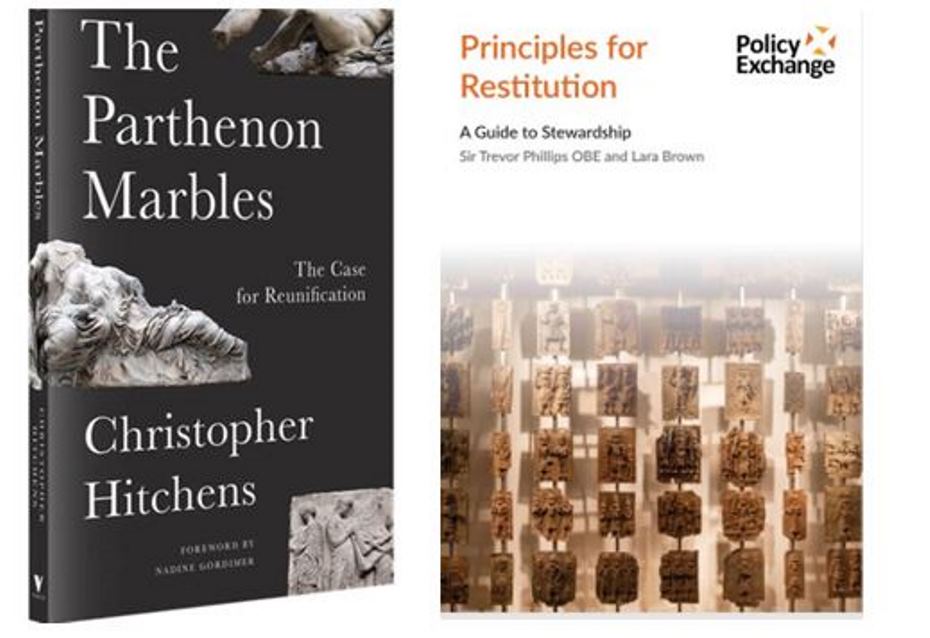

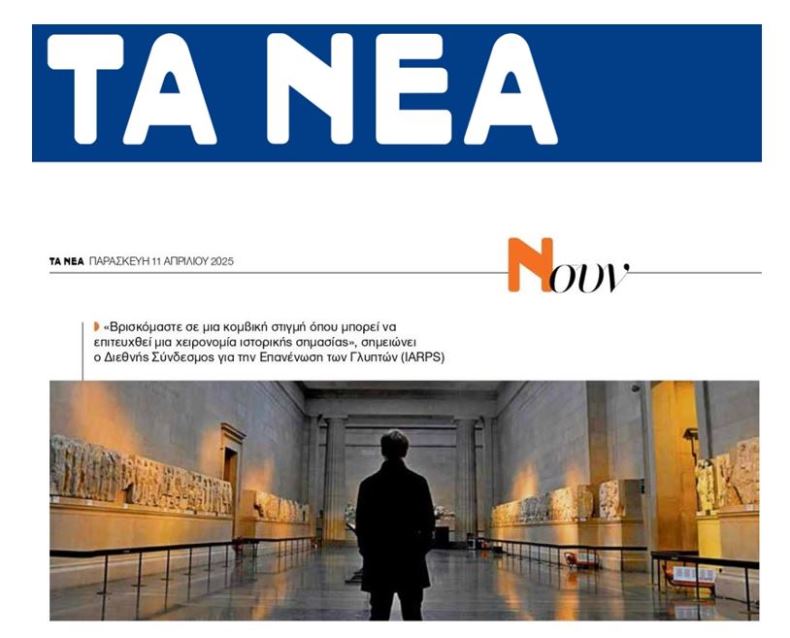

For many years, the British Museum’s hard “no” to the repatriation question has set the tone for the global reputation of the UK museum sector’s stance on the subject.

In the meantime, other European countries have made rapid progress on repatriation, beginning with the 2018 Sarr-Savoy Report, commissioned by French president Emmanuel Macron, which seemed to indicate that France was ready to return all stolen African belongings in its collections.

Then in 2019, Germany released a framework and guidelines for repatriation issues. These developments, alongside other European countries releasing national policies and even passing new laws, have gained momentum and been widely reported in the press.

This widespread awareness of the advancements in national policy elsewhere in Europe, coupled with the UK government’s anti-repatriation stance, has all served to make the UK sector disillusioned with its own progress towards repatriation.

Threats from the government have left some people fearful of the term “decolonisation”, let alone acting on returning stolen collections.

Lots has been written about the lack of action Britain is taking towards repatriation, and how we are falling behind our European colleagues. But when one digs deeper, the picture of progress across Europe is not as it seems. Fewer than 60 items have been returned to African countries from France, for example.

While museums cannot afford to take the pressure off the UK government to change its position on repatriation, it is important to acknowledge the number of returns that have happened in recent years.

These have been made possible by Indigenous activists and a small number of museum curators committed to making this work happen.

Organisations that have repatriated items include the Horniman Museum, University of Aberdeen, University of Cambridge, Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Manchester Museum, Buxton Museum, Bristol Museums, National Museums Scotland and Glasgow Museums.

These returns demonstrate the huge amount of work happening in the UK. Repatriation is a long process, so for these returns to have happened in spite of the government’s posturing and critics saying the sector is not taking enough action, is quite an achievement.

I describe them as “achievements”, not for museums to pat themselves on the back, but because our global reputation prevents more Indigenous Nations making claims with UK museums, as they believe it will be a blanket “no”.

This is partly because the narrative about the UK government and our perceived backwardness on the topic overshadows what many in the sector would like to promote – an openness to return akin to our European colleagues.

So how do museums in the UK change this reputation and communicate that they are open to repatriation claims? Given the number of returns that are happening, we have the opportunity to be leading on repatriation in Europe – but nobody would know that from the current narrative.

And, if all this work can be done in spite of the government, imagine the progress we will make when there is a national push to repatriate. Let’s keep going and raise awareness that while we might not have huge resources, we’re open to returning ancestors and belongings home.

Amy Shakespeare is an AHRC-funded PhD researcher at the University of Exeter and a freelance consultant

Amy's article was first published in the Museums Journal on 29 November 2023.