Did you know that Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, wanted to acquire sculptures from a site in Greece in 1804 during his stint as Ambassador to the Sublime Porte? Your probably do. It’s a familiar story, but doesn’t the date seem a little off? What if I mentioned that the site in question is ancient Olympia, not the Athenian acropolis? Yes, he tried it twice – he didn’t even have the excuse that he needed the money at this point, as he didn’t bring divorce proceedings against Mary Nisbet until 1808. Some of these facts and figures we know very well, but AE Stallings’ article 'Frieze Frame: How Poets, Painters (and Actors and Architects) Framed the Ongoing Debate Around Elgin and the Marbles of the Athenian Acropolis' in the 75th anniversary edition of the Hudson Review is a treasure trove of lesser-known trivia about the history of the marbles debate, much of it in the public domain despite its obscurity. For example, did you know that Morosini, the Venetian commander who ordered the direct hit on the Parthenon-cum-munitions store in the siege of 1687, always took his cat Nini into battle? Or that his munitions expert was a Swede, Count Konigsmark? Or that Nini was stuffed and is now on display at the Mueso Correr in Venice?

Perhaps it’s to be expected that there were other British travellers, like John Bacon Sawrey Morritt and Lord Aberdeen, who sought to take souvenirs of the Parthenon Sculptures in 1795 and 1803 respectively. But to find out that the latter was on the select committee of 1816 feels like a genuine surprise. We even find a kinship with Thomas Bruce, who also never saw the sculptures that bore his name for so long in situ on the Parthenon. In fact, he only spent a total of 59 days in Athens. It stands to reason that Envoys Extraordinary and Ambassadors Plenipotentiary are too busy for much sightseeing – though a successor of his, Lord Strangford, did request a firman guaranteeing the security of the Parthenon during the two sieges of the acropolis during the Greek War of Independence. There are a good few firmans in this article, some of clearer provenance than others.

What Stallings does well is present trivia, even facts one took for granted as general knowledge, in a way that gives them historical context, and makes revelations of them. An hour-long debate, however, can’t rely on the luxury of historical rabbit holes. Intelligence Squared hosted a lively event online entitled Return or Retain? The Parthenon Marbles Debate in September, between former cabinet minister Ed Vaizey, representing the Parthenon Project, and Sir Noel Malcolm, Fellow of All Souls, Oxford. Before the debate proper, chair Manveen Rana polled the audience on the question, “Should the marbles go back to Greece?”, with 81% for yes, 17% opposing the motion, and 2% undecided. A good start. By the end of the debate, however, those figures stood at 73%, 26%, and 1% respectively.

That’s a little frustrating, despite the net result being a win. Though Ed Vaizey had strong arguments for restitution, he went about his contributions like a politician - hammering certain soundbites (mostly about the benefit of new treasures coming from Greece to UK in return for the marbles, which is a Parthenon Project objective) a little too often, not really responding to Malcolm, and being a bit ad hominem when replying to the latter, calling his arguments ‘ludicrous’ &c. but maybe that’s within the rules of the debating society game. He could have done with reading Stallings’ article! However, his account of being converted to the marbles’ cause once he was free of the need to follow the status quo as a member of cabinet (his opening spiel), was pretty darn good. We need to hear more converts speak up!

With Ed Vaizey being a member of the Parthenon Project, the prospect of loans by Greece of artefacts previously unseen in the UK was frequently brought up, vividly invoking the queues to see the BM’s Tutankhamun exhibit of the 70s. But he may have hammered this aspect a little too hard, allowing Noel Malcolm to poke holes in the practicality of, say, frequent exchanges of exhibits, sure to cause a few grey hairs among curators on both sides. The prospect of new loans from Greece is attractive (and let’s be reminded that it was first voiced by Greece to the UK government in 2000), but it would be the icing on the cake – perhaps even just the cherry.

Malcolm’s opposition relied on arguments that were old hat at best, and rather depended on Elgin’s Memorandum of 1815, which is the primary source for Elgin’s motivation and modus operandi (apart from the proceedings of the select committee). That memorandum seems from Stallings’ article more likely to be the work of his chaplain, the Revd. Philip Hunt. Malcolm clearly has an intimate knowledge of the power structures in Ottoman provinces and contemporary sharia law. He places a lot of trust in the firman of 1801 – the one that apparently grants Elgin the right to remove and that only exists in Italian translation - and perhaps if Vaizey had had Stallings’ article to hand, he could have pointed to the extreme dubiousness of that firman’s provenance, not to mention another (the third, pay attention), produced in 1805 that stopped Elgin’s agents from collecting any further artefacts.

Granted, Malcolm was generally the more impressive speaker and did much more thinking on his feet. But his bottom line is a deeply un-trendy one: that matters of the deep past[sic] must be held to a different standard than those of the recent past. This came up in his closing comments, and had they come any earlier, Ed Vaizey might well have asked: where’s the line? 208 years ago could be argued to be either. Vaizey’s opening statement made a good point, though he didn’t state it in as many words: that this is not a settled, long-standing matter repurposed for argument’s sake in a manufactured ‘culture war’. This has been a ‘live’ issue since Elgin’s agents started taking artefacts on his behalf in 1801 – before he had even reached Athens.

For example, we know from Stallings’ article that a Greek law of 1832, under King Otto, asserted that “all antiquities within Greece, as works of the ancestors of the Hellenic people, shall be regarded as national property of all Hellenes in general”. This is an example of the deep past rubbing up against the present of 1832 – and exercised in a legislative and geopolitical way that makes it harder to classify the early nineteenth century as the deep past to our present. Regard Hartwig Fischer’s 2019 comment in Ta Nea, that “[moving] a cultural heritage to a museum” is in itself “a creative act”, Stallings makes a very relevant comment:

One might add that it takes another step – a Keats for instance – to complete such a creative act. In Fischer’s sense, though, too, Morosini’s destruction of the building was also a creative act… turning a functional structure, in a flash, into a picturesque ruin, the stuff of Byronic backdrops. Also, if Fischer is right, then this creative act of Elgin and the British Museum is over 200 years old – its creative energy is entirely depleted.

Intelligence Squared’s event was perhaps a good barometer for where the debate is right now: arguments about the Greeks’ ability to care for the sculptures and the ‘floodgates’ argument (here referred to by Malcolm as the “slippery slope”) aren’t cornerstones of the BM’s argument, though they still cling to their status as a universal museum. However, as the polls show, if people are aware of the debate, they’re generally pretty well-informed, and need a fluent, multifaceted argument from the restitution crowd. We have that acumen, of course! Additionally, we must make it amenable to the BM and the UK to play an active part in reshaping themselves for 21st Century museology, rather than having their hand forced by legislation or the prospect of ostracization from the international community.

Some of the oldest chestnuts in the debate turn out to be much older than the era of Mercouri and ‘her’ BM Director David Wilson. Here’s Frederic Harrison refuting the floodgates argument, writing in The Nineteenth Century journal in 1890:

Of course, the man in Pall Mall or in the club armchair has his sneer ready – “Are you going to send all statues back to the spot where they were found?” That is all nonsense. The Elgin Marbles[sic] stand upon a footing entirely different from all other statues. They are not statues: they are architectural parts of a unique building, the most famous in the world; a building still standing, though in a ruined state, which is the national symbol and palladium of a gallant people, and which is a place of pilgrimage to civilised mankind.

With a few tweaks, that argument would do for us today, though happily it’s less needed as the ‘floodgates’ argument seems to have less currency as time goes on. The tweaks would have to be the references to “civilised mankind” and a “gallant people”, both hints at the race science taken for granted by the Europeans of 1890. Stallings doesn’t shy away from the way that the Marbles were used as both exemplar and evidence to the pseudoscience of colonialism, both in the conflating of whitenesses (marble, skin) and in Elgin’s first money-spinning ruse: exhibiting the sculptures in the presence of naked prize fighters to draw the line between the idealised ancient Greek nude and the peak condition of British athletes’ ‘Nordic’ physiques. I never expected to learn so much about the burgeoning craze for boxing in the 1810s from this article, but there we are. There’s something perverse about learning about half a dozen relatively obscure young men of modest backgrounds because of their brief fetishization by aristocratic aesthetes – yes, Byron was there in the shed on Park Lane, taking in the sights. One of the boxers, John Jackson, was his personal trainer.

Even without the pugilists, the dramatis personae and bibliography of Stallings’ article is exhaustive. Even Napoleon Bonaparte is there (he refused to buy the Marbles from Thomas Bruce). It’s interesting to note that, of the more than one hundred people who wrote, painted (and spoke and drew) in the two centuries-long debate, few Greeks or women appear before the Twentieth century. Likewise, there seems to be a relatively quiet period between the 1930s and ‘80s – perhaps it was this long hegemony, and the BM’s arrogance, that precipitated Mercouri’s campaign coming along when it did.

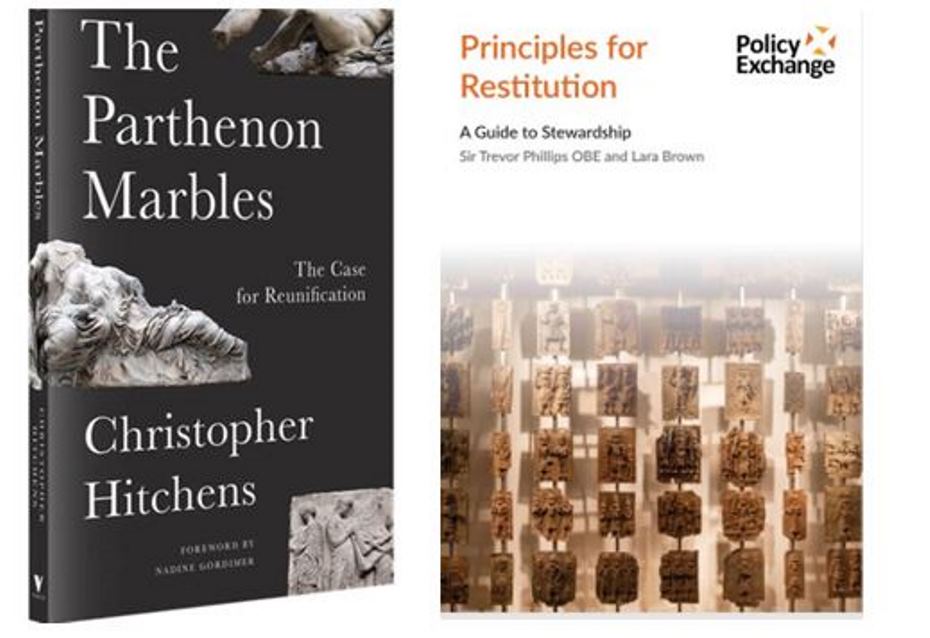

Stallings’ article is hefty – 110 very readable pages – and should be published as a standalone pamphlet. If that were to happen, it would surely be the best survey of the Marbles debate for the general reader since Christopher Hitchens’ The Parthenon Marbles: The Case for Reunification which came out in 1997, and the third edition published by Verso was launched at Chatham House by BCRPM in May 2008. To finish, here’s what CP Cavafy, probably the most famous Greek after Pericles to appear in this article and one who was raised in the UK, in Liverpool, wrote in the lengthy letters page debate started by Harrison’s Nineteenth Century polemic:

It is not dignified in a great nation to reap profit from half-truths and half-rights; honesty is the best policy, and honesty in the case of the Elgin Marbles[sic] means restitution.

Stuart O'Hara, BCRPM member

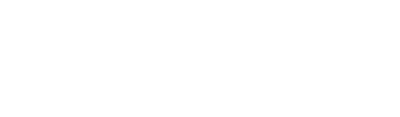

Image copyright Matthew Johnson (2018)