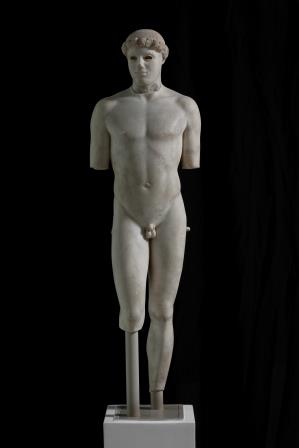

Jonathan Sumption dismisses any questions that might arise about Lord Elgin's legal title to the sculptures removed from the Partheon at the start of the 18th century. His article 'The Elgin Marbles weren’t stolen — Greece is just exploiting our weakness' (thetimes.co.uk) goes on to state:

"For most people, however, the issue is moral and cultural, not legal. So be it. What would be morally or culturally admirable about removing the Elgin Marbles from a museum in London to a museum in Athens?

Cultural artefacts have always moved around the world."

To read, BCRPM's Chair, Janet Suzman's response to Jonathan Sumption, please follow the link here.

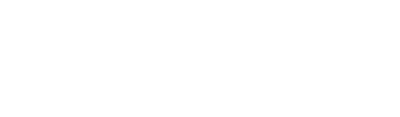

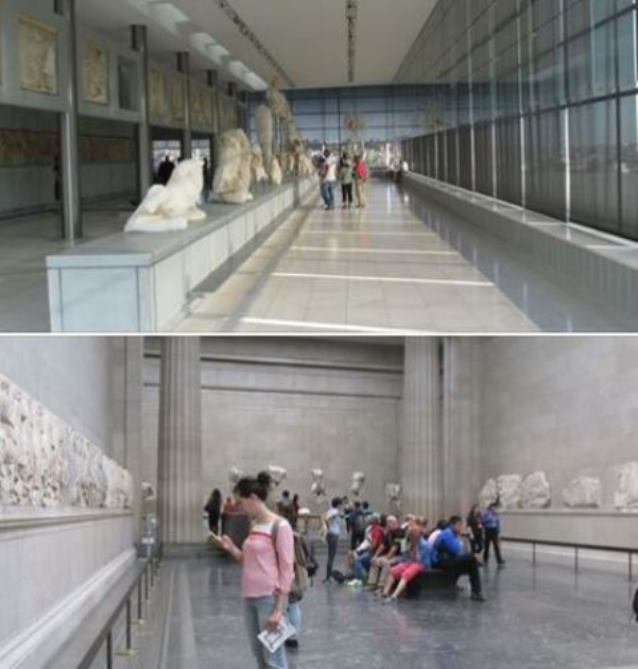

Christopher Price, long servicing Vice -Chair of BCRPM, wrote extensively on the merits of cultural mobility, and yet when it came to the Parthenon Marbles, he would have argued that they deserve, (those that survive), to be seen in the context of the Parthenon. An iconic structure, which not only stands, and has been restored and preserved for all humanity, but one that crowns the Acropolis. The emblem of UNESCO.

Jonathan Sumption goes on to list fragments of the sculptures from the Parthenon elsewhere: 'Paris, Vienna, Copenhagen' yet forgets to mention those museums that did have fragments, and that have returned them to be reunited in the Parthenon Gallery of the Acropolis Museum. Those frafments include returns from Heidelberg, Palermo and The Vatican.

BCRPM agrees wholeheartedly that the Parthenon Marbles, culturally have a great significance for all humanity, yet is right for the UK and the British Museum to dicate how that cultural patrimony ought to be exhibited and understood, even appreciated by all humanity, especially as the removal of the pieces still in London took place when Greece had no voice?

Even without the sculptures in Room 18, the British Museum would still retain its status as a universal museum. In fact it would be elevated even further. For it is cultural co-operation in the 21st century that matters to most. Any references to cultural dispute sound so out of step, and look at the reaction at UNESCO's ICPRCP sessions especially towards the UK and in relation to this impasse. Culture matters, and it matters globally. In the case of this very specific request, Greece's ask is wholly justified. BCRPM's founders, with past and present members, stand by this, as do many all over the world.

Jonathan Sumption goes on to write: "Let no one say that the return of the marbles would set no precedent. The world is watching this dispute.This is a fight that we cannot afford to lose, and certainly cannot afford to concede." And yet again, this is misleading. No mention of the fact that in the British Museum there are 108,184 Greek artefacts, of which only 6,493 are even on display. Or that this is the ONLY request made by Greece since independence, and continues to be the only request made to this day.

The world is watching but only in astonishment at the UK's lack of that very British sense of fairplay. Dare we add, diplomacy and regard for international relations too? How can we forget PM Sunak's decision not to meet with PM Mitsotakis in November? Will any Greek person, or anyone around the globe, forget that snub? Many however, were in admiration of King Charles' tie, worn at COP28, when he met with PM Sunak. The message? Not all world leaders behave like a Head Boy that's not prepared to do more than cancell a pre-arranged meeting that covered timely topics including the continued division of these specific sculptures.

"The Greeks are pressing their claim because they sense weakness. Since it was first formally advanced in 1983, they have skilfully exploited the relentless denigration of Britain’s past.They calculate that modern Britain lacks the self-confidence to defend itself. Are they right? The present negotiations implicitly concede that they may be.

Rishi Sunak should probably not have rudely cancelled his meeting with the Greek prime minister. But his statement that it should be unthinkable for any responsible British prime minister to contemplate ceding possession of the Elgin Marbles showed a sounder instinct than George Osborne’s." Concludes Jonathan Sumption.

The first request for the return of the sculptures removed only from the Parthenon, came shortly after Greece gained independence. Jonathan Sumption's reference to 1983 is the plea made by Melina Mercouri at UNESCO and that was the year that BCRPM was founded, nearly 150 years after the first request. Repeated requests made by Greece for these specific sculptures. So many have worked on the ways that would make the reunification work, and continue to provide the British Museum with artefacts not seen outside of Greece. For the last 23 years the offer of 'other artefacts' to be made available to the UK, has been on the table too.

Many have voiced their concerns at the UK's lack of empathy or understanding. Polls continue to support the reunification, yet few voices, including Jonathan Sumption continue to justify the division of this peerless collecion of sculptures. BCRPM continues to also add: the time has come to do the right thing by the Parthenon, and to add another chapter to the story of these priceless artefacts. Tell the story.